Chapter and Verse

Rick Moody, Jonathan Lethem and John Darnielle on the crossbreeding of literature and pop

Given that 2005 was a banner year for literate pop, one during which the rich narratives of musicians like the Hold Steady and the Mountain Goats earned accolades in The New Yorker, and Chronicles Vol. 1, the first installment of Bob Dylan’s memoirs, got nominated for a National Book Award, the L.A. Weekly thought it was high time to discuss the trend toward literary pop and pop literature. To that end, we convened a roundtable (albeit an electronically mediated one) consisting of novelists Rick Moody and Jonathan Lethem and musician John Darnielle. All are known for bridging the worlds of music and literature and for helping to erase the false boundaries dividing them.

To get things started, we posed a kind of theological question: Does your taste in music mark you as a Dylanist or an Enoid? To translate from music geek into English: a Dylanist (after Bob Dylan) would be a hot-blooded, essentially literary explorer, while an Enoid (after producer and Roxy Music keyboardist Brian Eno) would be more concerned with the sonic challenges of texture, form and space. As you might expect, our panel was seldom at a loss for words, and the music never stopped playing in their heads.

RICK MOODY: The question of influence is not unknown on the book-tour circuit, and it’s a question I rarely answer the same way twice. I like the Bloomian notion that whatever the real influence is, it’s always being concealed. I mean, I love Montaigne, but am I telling the truth when I say I was influenced by him? I dunno. Maybe I am not gifted enough. The question of cross-genre influences is even more slippery. Can I be influenced by Dylan? I certainly played the hell out of Blood on the Tracks while writing Purple America.

As far as Eno goes, I remember thinking, when I was 17 or so, and so besotted with Before and After Science and Music for Airports, that my two modes were really trance/minimalist and Old Timey. I liked experimental music, and I liked the oldest music imaginable. These things are probably allied. I do like music that drones a lot (LaMonte Young, Ingram Marshall, Carl Stone, Stars of the Lid, Godspeed, etc.). And then I like a lot of Appalachian music. And very early acoustic blues. Skip James, right now, is one of my favorite musicians. Dock Boggs. A lot of that Alan Lomax stuff.

JOHN DARNIELLE: To me, “musical influences” are so much less important than literary ones. My chief sources are: Joan Didion, the best writer alive and the most interesting person on the subject of what narratives are and how they work or don’t; Faulkner, though it’s been so long since I read him that the main memory for me is the florid descriptive technique, with which I have a complicated relationship; John Berryman; Robbe-Grillet lately but hugely; also recently wielding a big ol’ influence stick is William Gass’ The Tunnel; Seneca’s plays. The list is long, but I feel I’d be a poor sport if I didn’t actually name some musicians/lyricists whose craft I envy and whose phrases I’ll corrupt and steal: Nick Cave, but not recent-vintage Nick Cave; Lou Reed; Mexican singer Ana Gabriel just for purity of tone, transparency of craft, overall awesomeness; Jimmy Reed; Iron Maiden; Jeffrey Lee Pierce; Randy Newman, certainly; Steely Dan. These last two write very complex stuff which I couldn’t hope to match, but again, the main thing for me is what’s going on lyrically, and Donald Fagen and Randy Newman both do some really gorgeous method-acting, and neither one’s tempted to wink at the camera too much, if ever — the most important thing when you’re adopting a persona.

JONATHAN LETHEM: Camden Joy once made me very happy by saying that if my collected writings were a band, they’d be Yo La Tengo, and that thrilled me because it felt right (if you grant that I’m as good as YLT). Like them, I’m openly aware of standing on the shoulders of giants. Like them, I make sporadic use of Dylanesque personal gestures and Enoesque (Enoid?) self-effacing experiments, but don’t lock down into either mode. The comparison felt like the most flattering one I could consent to. I mean, if someone called me the Dylan of novel writing I’d be flattered, but forced to shout back, “You’re a liar!”

Like Rick, I listen to music while I write. And sometimes I’m certain of its influence. Some of my fiction’s influences are worn on its sleeve, but others are quieter — the John Cale song “Dying on the Vine” was the emotional keystone for Girl in Landscape. Other times the music’s just making me happier, less lonely, and therefore likelier to stay at my desk.

My persistent feeling about “influence,” though, is that I’m never not entering a room where the good conversation’s been going on long before I got there. I have a philosopher friend who describes her work as “filling in a small quadrant of philosophical space” — and by that she means one that is in some way already implicit by the presence of other filled-in quadrants but has not yet itself been filled in. This description sounds to me like 90 percent of what I do: explain, by my writing, how I saw a relationship between two different things that excited me, one that might not have been visible — or indeed existed — until I made my “explanation.”

L.A. WEEKLY:It’s interesting that both Jonathan and Rick avoided the idea of influence and spoke instead of how music helped inspire the actual writing process. My suspicion has always been that music offers a unique fuel for writing because it can establish an emotional state with such an economy of means. Is music the ultimate Cliffs Notes version of emotional experience? Must writers inevitably be a bit jealous?

DARNIELLE: A good piece of music, however ornate, is essentially a primal experience. Sylvia Plath referred to her infant’s cry as “a handful of notes,” and numerous studies (I know, I know, “numerous studies,” but still) suggest that we respond to music even in utero. Once we’ve learned how to arrange notes or apprehend their arrangement, we get it both ways: something both intensely physical and entirely theoretical, the condition of music being greatly abstract in the end.

MOODY: What inspiration means is almost as complicated as the question of influence, in that the old use of the word — God breathing through you — is pretty hard to verify. When I was a young writer, I actually bought the idea that drinking while writing would help me feel open emotionally, and that’s one of the reasons that Garden State is a very bad book. Once I quit, it became kind of hard to find that place, the receptive place that makes compassion and intuition happen. I think you can get to the “inspired” place through non-musical means, if you are willing to. Yet music points to that topography effectively, and for me, as someone who is very passionate about music, this is invaluable in composition. But I do feel the same way about painting and sometimes photography. The museum can do exactly what we are trying to describe. Music, on the other hand, has specific formal properties that I do want to ape, because they lie outside of the ordinary sphere of things. For example, The Black Veil was built on ideas about structure elaborated by Miles Davis when he was talking about how some of the fusion albums were constructed. That is, I guess, inspiration of a sort.

LETHEM: Someone said, “All art aspires to the condition of music,” meaning, I always figured, that abstract-essential-rarefied nature that John alludes to. I am struck by the fact we all come out singing, inflecting notes, and one of my favorite factoids is that children in every culture tease one another using the same singsong intervals to make “Nya-nya-nya” sounds. In other words, kid-to-kid humiliation is encoded in a musical tone like DNA. I bet a lot of others, like me, imagine what kind of music we’d want playing around our deathbeds, too — whereas I don’t spend any time wondering what kind of paintings or movies (or wallpaper) I’d want around me at the end, or what books I’d want to go out reading. Music is somehow both further up in the sky and deeper down in our bodies than the other arts.

That means it often has to shoulder the burden of being the art that other art flatters itself by bending toward. I’m never confused that it’s anything but praise when someone describes my writing as musical, though I suspect it would be neutral at best to call any musician’s work “prose.” If you told me my book was like a film, I’d have to look deep in your eyes to be certain you weren’t getting a dig in. If you told me it was like a painting, I’d know you were trying not to tell me you couldn’t finish it.

Another truth, more simple, is that one grows weary or jaded with an art that’s been so completely domesticated and professionalized: So we imagine that those musicians are really still like pure and innocent creators, while we writers are so bogged in crappy minutiae — we’re like stenographers compared to them! Put a guitar in my hands and let me be dreamy and youthful again!

More talk about pop music is in order! In 2004, the most debated article in music crit was Kalefah Sanneh’s “The Rap Against Rockism” from The New York Times — a defense of manufactured pop in the wake of Ashlee Simpson’s Saturday Night Live lip-sync flub. My sense is that some newspaper critics invent theories to justify liking this kind of music, because they’re forced to cover it for the broad newspaper audience. But there’s another possibility. I enjoyed Britney’s “Toxic”; Amerie’s “1 Thing” was my favorite song this past summer; and, hell, I love Tweet, who’s thought of as anathema to critics. Can’t lite-pop be profound?

MOODY: I love pop songs, too. I swear. I actually love ABBA, and Fleetwood Mac is incredibly important to me, and my first worshipful relationship to a rock & roll record as a kid was to Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. I tried hard to get the Wingdales to cover “Beautiful” by Christina Aguilera before Clem Snide went and ruined it for me. It’s really all about compositional smarts, and a really good pop song is a really good pop song, whether it’s by Neil Diamond, Tommy James, Simon & Garfunkel, or Lothar and the Hand People. The verse-verse-chorus-verse-bridge-chorus-chorus model is not that different from a sonnet in a lot of ways, and just as difficult to perfect.

Performance is something else altogether. My rule of thumb is if there seems to be a credibility problem, there probably is. For example, I can’t help feeling that Britney Spears doesn’t sing that well, can’t dance and can’t write her own material. I suspect other people feel this way too and just like the cultural garishness of Britney, and that’s where I get confused. I get ill-tempered when there’s a reactionary thrill about liking stuff that’s corporate and overly format-conscious just because there’s so much of this stuff around, we might as well start liking it, because what else do we have? Through the same tortured logic, we start talking about how great American beer is, or which is the better 99-cent store.

Eminem is another good example. I confess he knows a lot about enjambment and how to vary line lengths. But there’s a lot about him I just don’t understand. To my ears, the beats and samples are really dull. If you listen to Terminator X and the Bomb Squad and then listen to what Dr. Dre has done on the Eminem albums, it’s really hard to understand what’s so good about the sound. It’s tinny, like advertising music, like he’s trying to sell hamburgers. From a political angle, it’s important to mention that he did advocate cutting his wife up and putting her in the trunk, right? I am used to being told that I am being oversensitive, but I don’t want to listen to him on this subject, and my repugnance has nothing to do with his success. If literature is about complexity and subtlety, then Marshall Mathers doesn’t have the thing that makes me want to stay with a piece of art. I understand that the form has hyperbole built into it (thus the cutting up of the wife), but it just doesn’t translate for me.

DARNIELLE: This is an insufficient response, but I must say the Backstreet Boys merit more than a passing glance, because they sing like angels and because I worked with children when the Boys were at their commercial zenith, and, well, when you lock into the joy that pure, treacly pop inspires in children, it’s a lovely wave to ride. I don’t think that everybody who embraces “dumb” pop is doing so from a transgressive urge, and in the end, I’m not sure that it matters what inspired the opening of the ears.

Rick’s dismissing of Eminem bears a little closer scrutiny, too, because Em’s craft isn’t just “good,” it’s for the ages, and there’ve been plenty of artists through history with considerably darker muses. In 10 years’ time, I think even his most violent fantasies will sound removed from the Zeitgeist, like the murder ballads they are. Dylan covered “Love Henry” a few albums back and nobody complained about it, and Nick Cave got a free pass for a whole album of gruesome murder ballads. Why the special animus for Em — because he’s more popular? Because kids like it? Because he prefers not to drop the mask? Yes, the centurylong tendency to claim low culture for high art, and the infatuation with this gesture, is an annoying reflex, but let’s not toss the baby with the bathwater.

I’m hoping I can inspire some summary thoughts: What should the world of music take away from the world of literature, and what should the world of literature take away from the world of music?

MOODY: Maybe what’s binding rock & roll and writing together these days is the sense of both forms becoming a less central part of the market-driven, homogenized, vertically integrated global culture. They are becoming like attractions in some historical theme park, a theme park with markedly bad attendance. When a form is neglected enough to be intimate, it’s more appealing to me anyhow.

To put it another way: The musicians who are interested in collaborating with writers are musicians who are readers. And what, finally, is more exiguous in the politics of the moment than reading? Virtually nothing in America supports reading as a way of life. Try reading in an airport. Likewise, the writers who want to be in the orbit of musicians are people who are really engaged with what’s happening in the most artful and speculative wing of contemporary music. David Gates is out there learning Old Time music, Paul Auster is writing for One Ring Zero, Dave Eggers is composing for Cheap Trick 20 years after their last hit, Myla Goldberg is providing fodder for the Decembrists, Denis Johnson is turning up in a Sonic Youth song, etc. I don’t see any novelists volunteering to write lyrics for the Top 40. In my view, this interest is not at all because these writers want to be “rock stars” but because music is a warm, open, responsive language and is therefore lovable.

I figure the forms are already married to one another. One of my complaints about contemporary fiction is that a lot of it is secretly obsessed with a potential movie sale, and the way you can tell is that the work is more preoccupied with appearances, with the way a director might look at a scene, and this to the detriment of the sound of the prose. When Ezra Pound said that poetry was language cut in time, what he meant was that our art is made out of words, and when the words become merely vehicular, the means to an end, then the work becomes transparent and calculating. On the other hand, if the prose is made to be heard, whether this is aloud or in the still, secret auditory nerve of a private reading experience, then it’s only natural that it would want to interact with music, because song is the most perfect use of language. When a voice raises up the words in song, it’s a really splendid thing, a moving thing, arguably the most beautiful thing you can do with language. Who wouldn’t want to try to do that?

LETHEM: What a beautiful post, Rick. I’m going to jump in and free-associate from the last thing you said, since you’ve laid the ground so elegantly. If an attraction to music reveals the fundamentally vocal nature of the writing act in my own experience, it also nourishes the fundamentally irresponsible nature of that act. It seems to me that writing finds itself surrounded on all sides by, well, cops. Responsibility censors. Fiction writers are meant to be dreamers, yet we’re called on to pontificate on the tradition of our medium and on our fellow practitioners, to honor our elders with introductions to their books, to teach the next generation as though what we do is innately teachable. These are all potentially lovely or at least redeemable activities, but they drag us into the costume of rationality and responsibility. We publish in magazines mostly as a minority element amidst chunks of rhetoric, criticism, analysis, all of which, if you blur your eyes, might appear to be exactly the same as our pages. But imagine if music took place as an occasional interlude between long sequences of city-council meetings and corporate strategy sessions.

Now, I’m suspicious that rock & roll (and music generally) seems to be the special province for freedom, irresponsible creativity and Dionysian impulses inside a puritan culture. But the fact is that in my actual life and experience it is that province — a place where the methods of the irrational, sporadic, impulsive, incoherent self-contradicting creator are more rewarded and exalted than not. The literary realm seems prone to the reverse — we keep a few token outlaws on a leash around here, but they’re pets, not the owners of the house.

DARNIELLE: Jonathan makes a fantastic point about “rock-as-Dionysiac-domain,” though it’s absurd from the standpoint of the craft itself. There’s nothing wild and free and libidinous about Mick Jagger’s 33rd consecutive attempt to get just the right quantity of sneer into “I’m no schoolboy but I know what I like” in “Brown Sugar,” but the Rolling Stones are notorious studio perfectionists, and 33 is probably a conservative estimate.

I wish the music world would just embrace its entirely literary nature. Nobody’s worse with the “you gotta feel it!” junk than rock people. The problem is music from rock forward is construed as being “about sex,” which is at least partly correct. But there’s also this complicating notion that sex is “about youth,” or at least for youth. This problem does not exist in the literary world. Not to say that sex appeal doesn’t help sell books: It does, of course it does; but the whole culture of literature, across the magazine spectrum from NYROB to Granta to The Baffler to McSweeney’s, is less heavily reliant on this particular region of smoke and mirrors. I also wish the pop world shared the literary world’s open lust for verbiage. Once a year you’ll read an essay somewhere about how analyzing a song will kill it. Yaaaarrrrgghhhhhh. Hulk smash.

Contentwise, I don’t really draw any distinction between pop songs and literature, so they can’t really learn from each other in that sense, as they are more or less the same person.

***

THE BARDS OF THE ROUNDTABLE

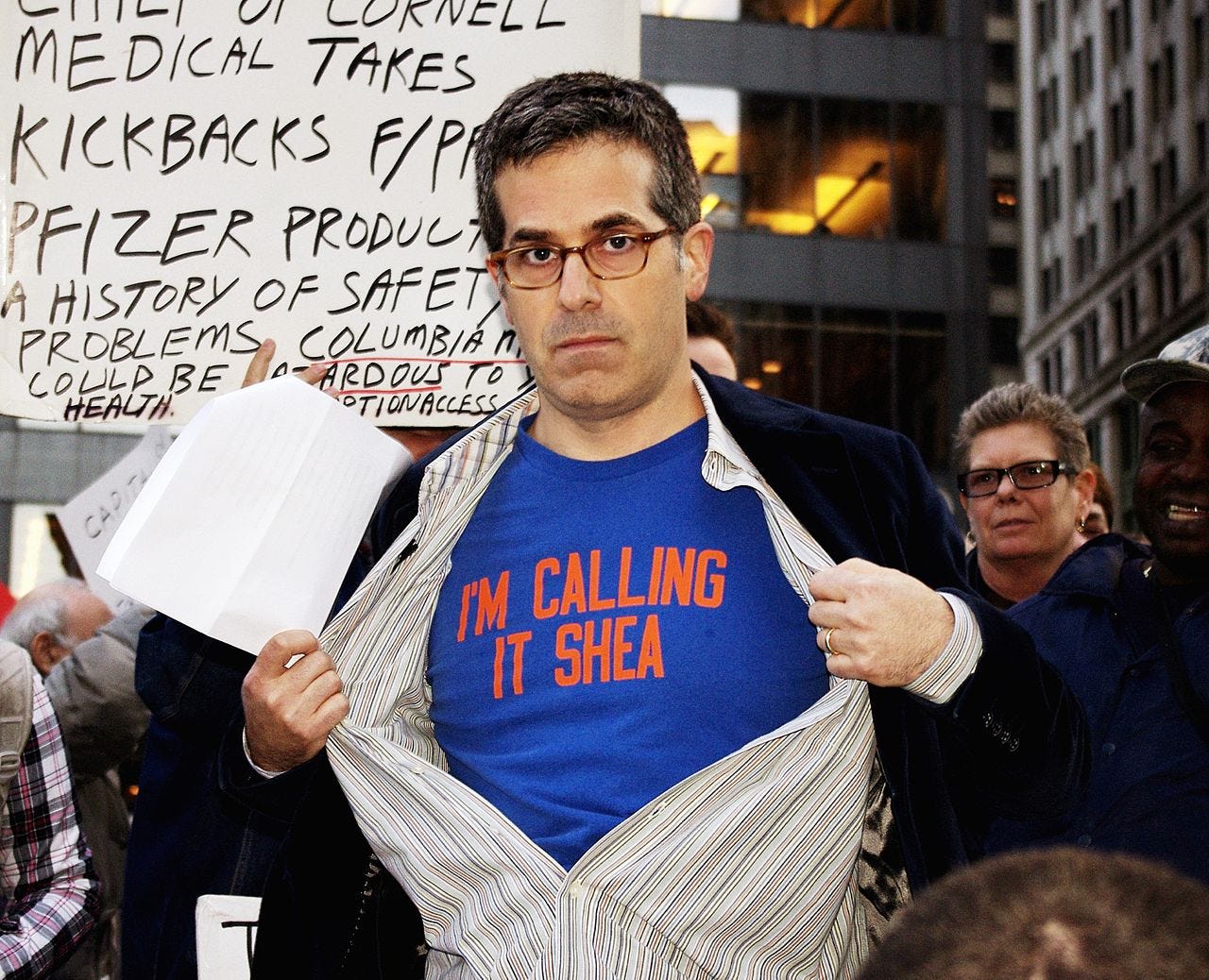

Novelist JONATHAN LETHEM is known for celebrating “junk” culture from comic books on down. Or up, depending on how much you value Jack Kirby. He has shown a special dedication to music. In 2002, he edited Da Capo’s Best Music Writing anthology, and the protagonists of his 2003 novel, Fortress of Solitude, are named Dylan (he’s a music critic) and Mingus (he’s the son of a faded soul singer). In the fall of 2005, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation awarded Lethem a MacArthur Fellowship, commonly referred to as the “genius grant.” His most recent book is The Disappointment Artist, a collection of essays.

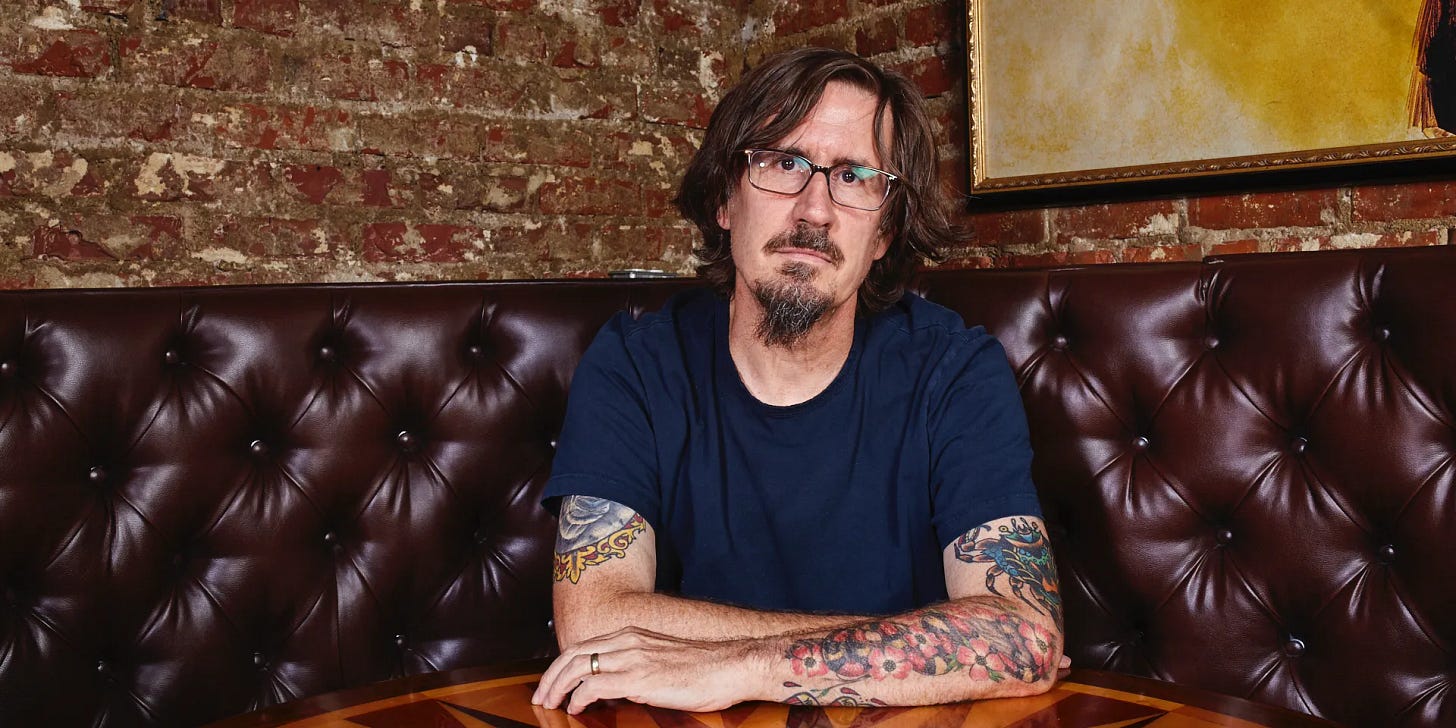

Novelist RICK MOODY has frequently made music his muse — be it with the Wingdale Community Singers, a band he has started with respected musicians David Grubbs and Hannah Marcus, or his debut novel, Garden State, which featured a small-time New Jersey punk group. (Some assert they were based on the Feelies. Moody really likes the Feelies.) His last novel, The Diviners, published last September, is a sprawling satiric book about, among other things, the hype-mongering that fuels Hollywood’s entertainment-industrial complex.

The lyrics of JOHN DARNIELLE, a.k.a. the Mountain Goats, have been celebrated as a great contribution to literary songwriting. If Bob Dylan is the poet of pop, and Lou Reed its first novelist, Darnielle’s music toys with geography, history and perspective in a way that can be aligned with postmodern fiction. Like many novelists, he is also a perceptive critic. On his Web site, Last Plane to Jakarta (www.lastplanetojakarta.com), he publishes funny, intelligent screeds about Thai pop, heavy metal, semi-mainstream hip-hop and anything else that strikes his fancy. He is a native of SoCal’s Inland Empire, and will release the follow-up to his 2005 effort, The Sunset Tree, later this year.

Originally published in the LA Weekly on February 28, 2006.