In 1996, you could walk into almost any bar in downtown New York and, within a few minutes, hear a song from Beck’s latest album, “Odelay.” Chances were you’d like it. It didn’t matter if you were into hip-hop, modern rock, or traditional blues — there was something about Beck’s music that was urban and new and made you want to dance. The song “Hotwax” began with a deep blues-guitar lick. A second later, funky beats and distorted guitars kicked in, and then quirky hip-hop-style vocals with a country-and-Western lounge-lizard overlay:

Sawdust songs of the plaid bartenders

Western Unions of the country Westerns

Silver foxes looking for romance

In the chain smoke Kansas flashdance ass pants

When Beck, who resembles a choirboy, with pale skin and a delicate frame, made a “shout out” to “two turntables and a microphone,” the irony was clear. This was music for a short-attention-span generation brought up on hip-hop, noisy rock, and channel surfing, as comfortable with street talk as with TV-sitcom references.

“Odelay” proved that “Loser,” Beck’s anthemic 1993 single (with its plaintively tongue-in-cheek chorus “I’m a loser, baby, /so why don’t you kill me?”), was not the product of a one-hit wonder. The album won two Grammys and sold more than two million copies. Geffen Records had found a pop star who could make party music that was marketable yet adventurous — the perfect antidote to the high angst of early-nineties grunge rock, whose popularity was beginning to wane.

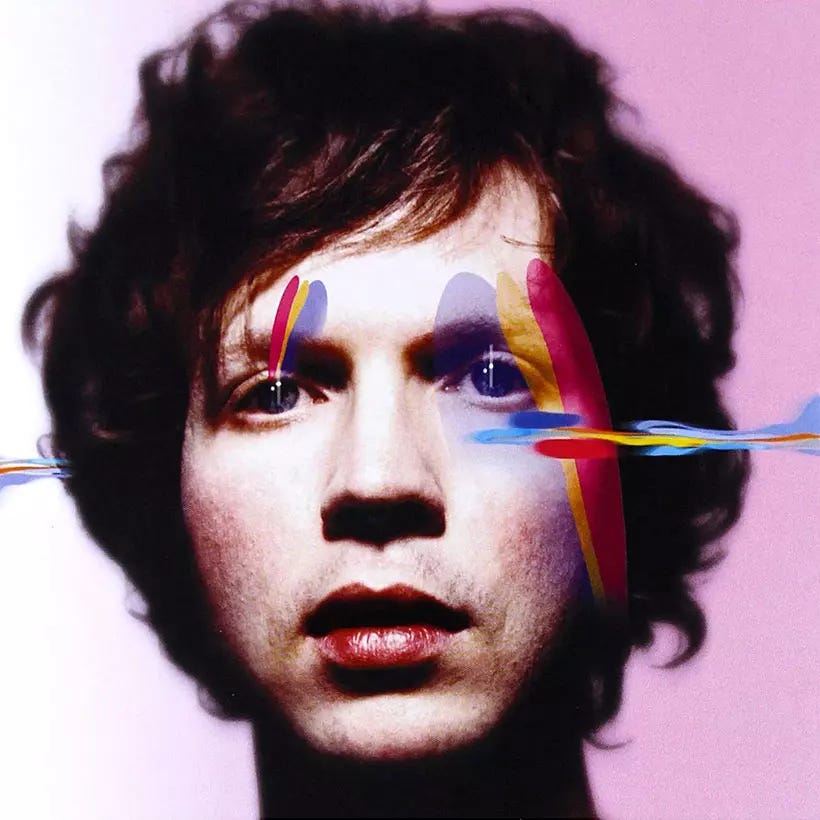

Then, two years after “Odelay,” Beck released “Mutations.” On the album’s cover, he poses with a serious expression on his face, draped in a transparent plastic sheath that he seems poised to remove, like a butterfly emerging from his chrysalis. The album itself was sober, sombre, and largely acoustic, drawing on psychedelic American and Brazilian folk-pop of the sixties. The arrangements were almost regal, and the songs had titles like “Nobody’s Fault but My Own” and “Dead Melodies.” The pop collagist looked as if he wanted to be Dylan. To confuse things more, Beck followed up “Mutations” with “Midnite Vultures,” a postmodern minstrel show that borrows liberally from a century of African-American pop, paying tribute to black vernacular music that most white musicians would never dare to touch. His homage was goofy (lyrics like “Hot milk / Mmm . . . tweak my nipple”), and the album got written off as parody, mostly because critics couldn’t understand why Beck would want to make it.

***

Of the musicians active today, few deserve the title recording “artist” more than Beck, although he would not use that term. He has a virtuosic musical talent, and is able to pull off credible impersonations of performers in virtually any musical genre. Born in 1970, Beck is the son of a lower-echelon Warhol Factory girl by the name of Bibbe Hansen and a Hollywood arranger and Scientologist named David Campbell. He was raised in and around the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, which was a kind of racially mixed bohemian ghetto. His maternal grandfather was the artist Al Hansen, who was part of the Fluxus movement, a loosely organized collection of interdisciplinary artists devoted to finding “alternative channels” for art. Members included Yoko Ono and the “mail artist” Ray Johnson. Al Hansen’s specialty was turning trash into art. He made thousands of images inspired by a prehistoric fertility icon named the Venus of Willendorf out of Hershey’s wrappers and used matchsticks. When Beck was a child, Al enlisted him to walk up and down Sunset Boulevard collecting cigarette butts for use in his collages.

Thanks to this upbringing, Beck has always assumed that low culture and high art could go hand in hand; he must have figured that as a pop star he would be able to root through the detritus of twentieth-century music without having to pick up cigarette butts. But his combination of wide-ranging talent and formal diffidence raises a question: Does a musician have to commit himself to one sound to be taken seriously?

Over the last fifty years, rock and roll splintered into dozens of subgenres, all of which are categorized as “popular music.” Traditionally, musicians make their name by choosing a genre and becoming associated with a sound that their fans get attached to. As Beck’s new album, “Sea Change,” demonstrates, he is making a point of refusing to choose. The title may overstate matters, but the album represents a considerable maturation. Lyrically, there are no pop-cult name checks, no linguistic detritus. No “flashdance.” No “ass pants.” On the album’s best number, “Already Dead,” Beck sings about the feeling of missing a lover on whom he’d grown dependent:

Days turn to sand

Losing strength in every hand

They can’t hold you anymore

Already dead to me now

‘Cuz it feels like I’m watching something die

Love looks away

In the harsh light of the day

Not long ago, Beck broke up with Leigh Limon, a girlfriend he had been involved with since before his rise to fame, and “Sea Change” seems an effort to reconcile himself to this loss. The album may get at new emotional truths, but there are many albums about romantic loss. What’s most interesting about this record is that it sounds as if Beck is still concerned more with sonic form than with lyrical content. You can hear the lessons he learned from the tightly constructed soundscapes of “Midnite Vultures.” (Previous albums had foregrounded his songs’ rough edges.) Though the melodies on “Sea Change” aren’t remarkable, as pure sound the record is gorgeous. Like “Mutations,” the album is largely acoustic, filled in with a womblike warmth: supportive electric bass; ethereal slide guitars; atmospheric pianos, clavinets, and keyboards; gentle drums that melt away under layers and layers of mid- and low tones. Even the glockenspiel makes an appearance.

The arrangements are lapidary and seductive, and the record feels cohesive, despite the fact that we can clearly identify Beck’s influences. “The Golden Age,” “Guess I’m Doing Fine,” and “Lost Cause” have the Zen twang of cosmic country artists like the Flying Burrito Brothers. The dynamic build and release of “Little One” are reminiscent of Nirvana’s grunge rock. The arrangements of “Lonesome Tears” recall the symphonic R. & B. of Isaac Hayes’s “Hot Buttered Soul.” There are also echoes of the English folkie Nick Drake, especially in the finger-picked guitar of “It’s All in Your Mind” and the moody vocals of “Round the Bend.”

Beck offers no solution to the problem of loss, but he describes how tightly we grasp our illusions and misperceptions. “We’re just holding on to nothing / To see how long nothing lasts,” he sings in “Paper Tiger.” Even in a reflective mode, he suggests that the meantime is all there is. This attitude and the songs’ sprightly arrangements give the gloomiest lyrics a brighter spin. These are the best kind of loss songs—wistful, not pitiful; confident, not decadent; optimistic, not despondent.

Ever since “Mutations,” we’ve been waiting for Beck to reveal his relationship to the music he alludes to, mimics, and steals. But, all along, he has been a garbageman with a magpie’s eyes, picking over twentieth-century pop culture and making off with the shiny bits; he’s the grandson of Pop art. “Sea Change” helps us hear that the content of his earlier records is closer to autobiography than their formal pastiche suggests. When you listen to “Loser” after hearing this record, it sounds like an awkward revelation of hard times and high jinks from Beck’s bohemian adolescence: “So shave your face with some mace in the dark / Saving all your foodstamps and burnin’ down the trailer park.” By comparison, the sentiments expressed on “Sea Change” are universal emotional truths, not personal ones.

My hope is that Beck won’t abandon his jokey cutups for soul-baring poetry. A song like “Loser” is harder to take seriously than Beck’s new work, but it’s also funnier and more original. After all, ninety per cent of pop music is about loss, but who else has sung about a world made up of cowboys and breakdancers? Still, “Sea Change” leaves you optimistic about Beck’s future. He continues to make great formal leaps, and although he knows that pop music is disposable, he has finally realized that junk yards have their share of both trash and tragedy.

Originally published in The New Yorker on October 14, 2002.