Loving and Leaving the Phonograph

Why Napster, extraterrestrials, Southern hillbillies and Dick Clark mean more to the future of music than copyright and the Recording Industry Association of America

Beatrice I love my phonograph

But you have broke my windin’ chain

And you taken my lovin’

And you give it to yo’ other man

— Robert Johnson “Phonograph Blues”

LOVE ON RECORD

It’s mid-December 1999. Something’s almost over and we didn’t even know it . . .

I’m driving with Matt out to the warehouse barrens in Downey, California, far east of most of Los Angeles. Matt is dusky Californian blond; a proud wearer of chunky black glasses; owner of a 1978 Datsun painted metallic baby blue; the one who introduced me to the charms of blowing up hostage targets at LAX Firing Range. I.e., a record collector. On this drive, we’re listening to records, albeit digitally, on compact disc. At the moment the Rolling Stones. Let It Bleed. “Gimme Shelter.”

“This is not the same as listening to records,” Matt says. “When I listen to this, I don’t understand it. You can’t see it. Pick up a record, though, and you can look at the grooves, see where the bass rumbles, where the drums drop out, where the wave gets thin and then gets fat again. In sum total, ‘Gimme Shelter’ is this thick,” he says, bringing his hand to eye level and indicating a half-inch gap between his forefinger and his thumb.

A beat.

“’Freebird’ is a full inch.

“It’s like Brian Eno says,” explains Matt. “’Analog delays gracefully. Digital decays absolutely.’ Digital is just not the same.” This is the first of many points. “Having a collection of records proves you have history. You’ve been listening, buying, collecting for a long time. You’ve accumulated something. Flipping a record over takes energy. You have to get up to listen to it all the way through. This shows you’ll devote both time and energy to the thing you love.”

“Or that you’re misspending your energy, and wasting space,” I say. Born into the CD era, I’ve never really bought LPs. The compact disc sounds fine to me, but to a record collector an album is about more than music. It is a sublime object, more real than life.

Matt offers little debate. “The space argument doesn’t fly with me. People fill their living spaces with so many useless and ugly objects. And yeah, I know there are lots of record collectors out there who forget to tie their shoes, who have no friends, who don’t eat or eat too much, who don’t clean their homes, but so what?”

We’re on our way out to Erika Records, one of the last vinyl-pressing plants left in California. Erika traces its origins back to the ’70s, when a Hungarian family, the Dunsters, began to acquire the expensive machinery needed to press vinyl. The business was closed briefly in the ’80s when a member of the family’s second generation of record men, Joe, was caught bootlegging Rod Stewart Greatest Hits LPs. Joe was forced to divest himself of his record presses, but the family returned to records in the ’80s when Joe’s sister, Liz, opened the record label and pressing plant Erika. (It’s named after her daughter.)

“Records for her are like dolls are for other girls,” says Matt. “She still dreams of dressing and molding teased-out rockers.” Liz revived the business at the height of L.A.’s glam era, selling her Corvette to put out heavy-metal vinyl. Although her label quickly fell by the wayside, the manufacturing operation remains. (Liz and her husband recently began Independent Music Distribution, which will distribute records for a number of independent labels.)

When we get to the plant, an anonymous block of corrugated-metal buildings, Liz guides us out to the presses. We pass one of Liz’s workmen, a balding, 6-foot-4 man with a half-toothless smile, acid holes in his worn T-shirt, and cracked, sausage-thick digits. We are far from Malibu and Hollywood, but I imagine everyone here feels part of a glamorous lineage. The platinum and gold records lining Erika’s walls offer a condensed history of post-’50s pop: the Beatles’ Anthology, Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall, New Kids on the Block.

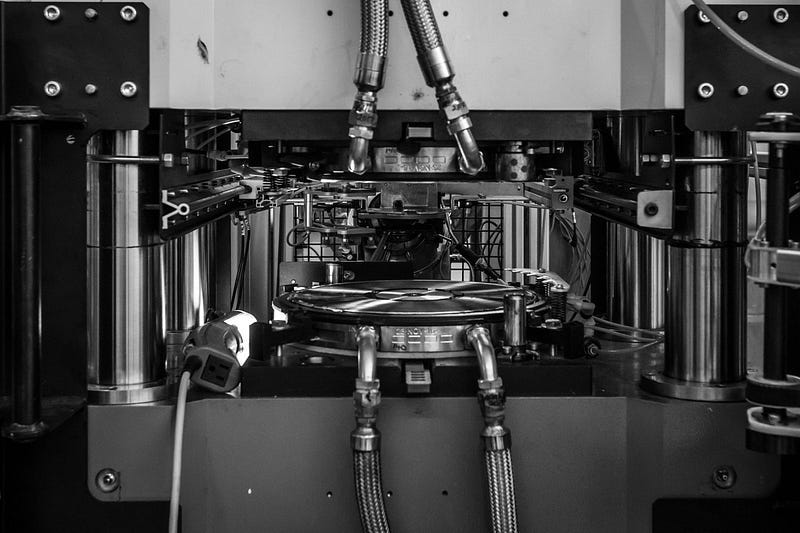

Erika is most esteemed for its expertise in creating custom records such as 7-inches in the shape of hearts or stars; records speckled with color like Jackson Pollock spin art; or picture discs on which the grooves lie over, say, an illustration of pneumatic breasts, a depiction of the devil or a metal band’s highly stylized photograph. To make custom records, though, you’ve got to make the things one at a time, by hand. To prove this, Liz leads us to the manual record presses.

A workman dressed in faded blue stands over the stamper, a specialized machine that flattens out hot vinyl into disc shape, inscribing the disc with an information-rich microgroove upward of a half-mile in length. Liz cuts in front of the worker and abruptly jerks the well-worn lever on the vinyl extruder poised above the stamper. It shits out a heavy, inch-thick mass of drooping black. Liz picks it up and drops it in my palm. It feels like a freshly harvested organ — steaming, dark and dense. I have to juggle the lump to hold on. “That’s 12-inches,” Liz says, smiling.

Matt and I are shuttled to Liz’s office. It is full of Elvis: Elvis dolls, skinny-Elvis stamps from the United States Postal Service, commemorative cups and plates, and a display of 7-inch singles. Liz sits behind a large, officious desk.

I’m here with Matt because he runs a label called Flapping Jet. It’s a tiny operation based out of his partner Max’s house in San Diego. Their focus is on vinyl records by destined-for-obscurity Scandinavian garage bands, clattering San Diegan rock, galloping drum patterns, barbwire guitars, men of limited range and talent screaming in key, and assorted agitated lunacy. Matt carries the artwork and master tape of his latest project in a brushed-aluminum briefcase.

Liz and I agree that in the album’s cover photo, the lead singer’s cheekbones look like those of Botticelli’s Venus. Matt leans toward Liz and places his hands on her desk, then whispers conspiratorially, “I would like to see us sell 10,000 copies of this record.”

“I would, too,” Liz replies, drolly.

“You know, if I told this to Max he’d go arraahgah!” Matt throws himself out of his chair and rips at his clothes, miming the behavior of a partner destined for penury. Matt and Max will spend many thousands of dollars pressing these records. There is a slim chance that they’ll make this money back.

“But, like me, you love it,” says Liz, “and we’ll never stop doing it.”

“It treats us well,” says Matt.

Liz shoots back: “Does it?”

CREEPING TOWARD DEATH

For almost two decades now, vinyl has been creeping toward death; in the 10 years between 1978 and ’88 alone, LP sales dropped almost 80 percent. Of course, vinyl will always be a viable way to store music, but LPs and singles are now as much objects and instruments as they are a medium for playback. They are pop-cult fetishes, an element of the turntable.

Matt and I go back and forth on the merits of one major label’s vinyl re-release of classics like the Stones’ Exile on Main Street. (“I just saw it at Aron’s for $45. What record collector doesn’t have Exile? Did people wear out the grooves? Did they sell their copies to buy some dope?”) There is still a fervent collector’s market for vinyl. DJs thirst for one-of-a-kind dubplates, inscribed on acetate. The reckless affection of people like Liz and Matt will always exist. But love has never staved off death.

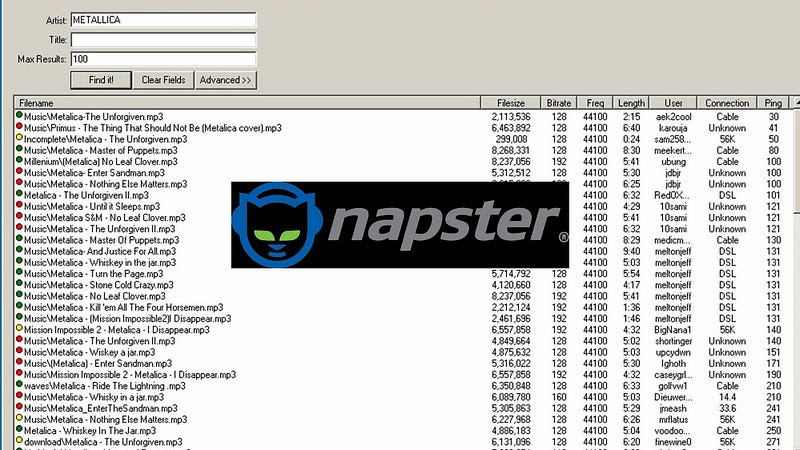

And now we have options such as Napster. In case you’ve been living in a bomb shelter without an Internet connection, Napster is a music-file-sharing application that narrowly escaped injunction at the hands of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) a couple of months back. (The RIAA is a trade organization and lobbying group for the ever in-flux major labels: the Canadian-cum-French Universal Music Group, Germany’s BMG, Japan’s Santa MonicaÂbased Sony Music, America’s Warner Bros., and Britain’s EMI, which may soon merge with Warner.) It is no exaggeration to call Napster a phenomenon. As a company, it claims as many as 28 million users and a valuation of close to $2 billion. As a concept, it has alternatively drawn the rancor, love and confusion of the industry, artists and music fans nationwide. If enough people download the application and log on to Napster’s servers, or utilize other peer-to-peer file-sharing applications of its ilk, all the recorded music in the world could conceivably be cataloged and available for free download via one central source. Because of Napster, the U.S. Congress or perhaps even the Supreme Court may be forced to reconsider the sustainability and enforceability of intellectual property and copyright. Some have accused Napster of hastening the end of music as we know it.

In light of this, it’s worth pondering Matt’s dedication to records and Liz’s apparent doubts: Does music, as it’s been sold to us for the last hundred years, treat us well? Should we celebrate packaged music or hasten its death?

There’s little question records have treated us well in the past. Well, okay, there’s no question they’ve treated me well in the past. Throughout my adolescence, punk rock records and their surrounding ephemera — fliers, magazines, T-shirts — provided documentary proof of a foreign but ever more accessible community apart from the suburbia I grew up in. Records were the gateway to a secret culture that seemed to birth itself, a self-willed community of sound based on rawness, lust, disorder and youth. It was a culture that certainly would have existed without records, but records best told the story and spread the song.

Whenever I begin to get wrapped up in records these days, however, I’m reminded that records are just objects. My nostalgia for these commodities is awkward and unwelcome in this, an era of frictionlessness, weightlessness, wirelessness and Web technology, and of frictionless, weightless talk about Web technology. Records are merely an amalgam of printed paper and flat plastic: garbage. They have become less real than digits floating through the ether.

As a collector, though, I’ve always engorged this garbage: B-sides, obscurities, the offshoots of the obscure; the gnarled or guileless or jaded sounds of pop. Thankfully, this particular garbage is small and portable enough that it can be filed neatly on a shelf, but these objects, this data you can hold in your hands — wax cylinders, shellac, magnetic tape, compact discs — has been accumulating on shelves for over a century. Call it a sign of personal growth, but these days, when I walk into the indexed sprawl of a record store, I don’t just see the unmatched possibility of popular art, I see the garbage as garbage, as glut.

Then I begin to think about the four or five corporations that sell the vast majority of those records, agglomerations that tend to treat their “entertainments” as packaged goods, like cereal or dish soap. I consider the explanation Sony made to its stockholders in 1988 when it spent $2 billion for CBS and Columbia Records, one of America’s greatest labels — it needed software for Sony hardware: disc players, microcassette players, Walkmans and the like. Then I contemplate the words of British stockbroker Edward Lewis, owner of the early gramophone manufacturer Decca, who recalled his rationale for going into the record business like so: “A company making gramophones but not records was rather like one making razors but not the consumable blades.”

As we think about the future of records, it’s well worth keeping in mind these attitudes, that what drives these labels is not “Give them music!” but “Give them razor blades!” Perched as pop culture is on a narrow fence between art and commerce, it is important to remember that the major players have nearly always fallen on the side of dish soap.

So ask yourself, Do records — CDs, LPs, cassettes — treat us well? And just how do these products treat music?

THE PAST

Before I get to the exciting part — Napster, Scour, Gnutella, Freenet, the future, free! — let’s consider the wonder of abridged history, how it can make the past seem recent and the present an aberration, how it shifts today’s debate from the world of commerce into the context of art and music.

History will tell us that before written language, humans made sounds — grunts, then indicative grunts, then chants, then music. Some theorize that it was our rhythmic voicing that first elevated us from the field of lesser mammals. It connected us, made us capable of massed action, aided memory. The “arraahgah” of Matt’s partner, for instance, may have meant “Help me. Save me from this other mammal. Kill it. Make it food.”

It wasn’t until 1877 that anyone recorded sound. Thomas Edison earned the nickname “The Wizard of Menlo Park” not for the electric light but for his invention of an early version of the phonograph. As much a device for recording as for reproduction, Edison’s first phonograph inscribed a paraffin-coated strip of paper with a wave of sound, then faintly played it back. This was a new apex in efforts to seize human life shifting in time, much eerier and more real than the brief moment caught in the flash of a photograph.

While the ideas behind the machine were not new — an invention called the phonoautograph had previously been used to draw waveforms representing a given sound — the physical fact of his own recorded voice left Edison with little idea what he might do with his discovery. His earliest notion was that recorded sound might be used for dictation or recording phone calls.

Within a decade, though, the visionary writer Edward Bellamy imagined what the modern communications industry now strives for. In a utopian novel called Looking Backward, 2000-1887, he predicted a future of ubiquity and unlimited choice, “An arrangement for providing everybody with music in their homes, perfect in quality, unlimited in quantity, suited to every mood, and beginning and ceasing at will.”

If you can’t get your head around how rapidly Edison’s invention became ingrained into our lives, we can bypass the next hundred years of history. We can skip the singers who feared that recorded sound would cause their careers as performers to dry up; we can bypass swing, Tin Pan Alley, jazz, race records, rock & roll and disco, and rejoin our story 100 years after the invention of the phonograph, in 1977. That year NASA launched the Voyager spacecraft, at the time the most ambitious attempt yet to explore the outer limits of the universe. Wishing to include a time capsule that would convey the story of our planet to whoever might find it, the agency sent a bunch of records encoded with images and music.

Along with the records was a needle and cartridge, and indications on how to play the record rendered in what appears to be a rocket scientist’s rendition of hieroglyphics. While the albums were sturdy, gold-plated 12-inch copper discs — not vinyl — in pictures they are recognizably recordlike. There’s even a label that soberly states:

THE SOUNDS OF EARTH

NASA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PLANET EARTH

Compiled by Carl Sagan and a handful of other scientists, the 90 or so minutes of sound include a Mexican mariachi band, heartbeats, footsteps, Beethoven, Bach, the bark of a wild dog, crickets, an initiation rite for pygmy girls, falling rain, preacher and blues singer Blind Willie Johnson, a mother kissing a child, and Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.”

Sagan, a master at understatement, placed the record’s import as such: “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

Little did he know.

Suppose, for example, that Voyager soars far past the sun’s magnetic field and the outbound currents of the solar wind. Imagine that an extraterrestrial discovers Sagan’s hopeful sign and that the creature plays the record, perhaps sharing it with extraterrestrial friends via some inconceivable mode of psychic transmission. Or let’s say it shares the sounds of Earth with a wide swath of its advanced spacefaring civilization. What might happen if, in sharing, a psychic copy is rendered? Well, it might run into trouble — playing “Johnny B. Goode” especially — because the American industry built around the hopeful sign might take a dim view of the extraterrestrial’s failure to pay royalties.

For it is not Chuck Berry but corporations that have turned music — the sound of falling rain and a young man’s howl — into objects, frozen sound they hope to hold rights to even beyond the solar wind. Here, for example, is how a contract might explain the Company’s relation to “Johnny B. Goode”: “Each Recording made or furnished to Company by you or the Artist either under this agreement or during the Term (a ‘Master Recording’ hereunder), from the Inception of Recording, shall be considered a work made for hire for Company.”

To “clarify,” that contract might add, “The Company shall have the exclusive right to copyright those Master Recordings in Company’s name as the author and owner of them and to secure any and all renewals and extensions of copyright.” And here’s where the spacefaring civilizations might run afoul of terrestrial jurisprudence: “All rights not specifically granted to Licensee by Licensor are expressly reserved to Licensor, in perpetuity, throughout the Universe.”

These are all direct quotes from the language of standard music-industry contracts. While the above-quoted terms are especially onerous, they’re not unusual in the kinds of legal documents a young artist might be asked to sign while wending his or her way through the machinations of the industry.

Only a lawyer could put these odd documents into context and explain how U.S. copyright’s tainted roots reach back into British law, such as 1710’s Statute of Queen Anne or 1556’s chartering of the Stationer’s Company. (The latter sought to prevent “sedition and heretical books, rhymes and treaties” by providing a mere 97 individuals the right to print books and by creating a Stationer’s Company to burn the books and destroy the presses of all others.) That same lawyer might also explain how the major labels have, in the wake of Napster’s emergence, begun using “artists’ rights” as a smoke screen masking their desire to maintain control of artists’ copyrights and, through those copyrights, a cartel-like hold on the profits reaped from the distribution of recorded sound.

But I’m no lawyer.

I do realize, though, that it flouts common sense and decency to grant Sony Music, Universal, Warner Bros., et al., rights that extend beyond the solar winds. Better to simply assault an industry that uses dense contracts to gain ownership over an individual’s creative work, and better to look to the logic of Chuck Berry, a true author of songs.

In 1955, Berry’s label, Chess, signed away a large share of the publishing rights to his classic song “Maybellene” to radio host Alan Freed in exchange for airplay. Berry eventually became so paranoid about being cheated out of such authorship rights that by the ’70s he had stopped looking to things like publishing to pay his way. Instead he began demanding prepayment, in cash, before taking the stage. He has, of course, been labeled “difficult.”

International conglomerates are not in the music game to do the good thing; when dealing with them, money on the table is the only thing to trust. There should be little sympathy for any pleas from any major label ever. Worrying about them is like heeding the boy who cried wolf, only far more stupid: They are the wolf and they cry and they eat young boys who hold guitars and try their best to hoot and holler their way from the heart of the woods into the solar wind.

THE PRESENT?

With all this in the back of your mind, you can begin to understand why so many look upon using Napster less as theft than as a new inalienable right. When I first tried it, I felt a wave of untrammeled possibility. Where else could I scan through — without toll — music I had only heard about and was dying to hear? Where else could my selection not be limited by a record store’s shelf space, a record label’s promotional budget, or whether a particular store manager thought a particular artist had a pretty smile or nice ass?

How else could I so easily connect the dots among the Georgian bubblegum of Tommy Roe’s “Sweet Pea” (“Oh sweet pea/C’mon and dance with me/C’mon c’mon c’mon and dance with me”); Bob Dylan’s “Lay, Lady, Lay” (“Forget this dance/Let’s go upstairs”); and the foul bounce of DJ Assault’s “Ass-N-Titties” (“Ass. Titties./Ass-n-titties./Ass ass titties titties/Ass-n-titties”), all without programming a track, flipping a record or tuning in to some magic station?

What could provide an easier way to relive the sweet release of my old records, like the part in The Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” when the verse slams into the chorus? Or the rubber-legged bass runs of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “White Lines” — a song whose bass lines were lifted from Liquid Liquid’s “Cavern,” initially with neither permission nor payment?

The more I thought about Napster, the more it seemed to me a distant relative of an earlier, similarly venerated bootleg, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. A collection of long-forgotten hillbilly and race records from the ’20s and ’30s, the Anthology was a carefully curated collection of unloved 78s drawn from Smith’s private stock or lifted from public libraries, then laid end to end. Its 1952 release was made possible by another piece of groundbreaking technology, the then-new long-play record. Again, it was an artistic work assembled with neither permission nor payment. (It was unavailable for decades after various labels came calling for royalties. These were labels that had happily let the original 78s — by artists most often forgotten or dead — fall out of print. It took Smith, a fan who died in poverty, to resurrect them.)

The Anthology is a collection that doesn’t sit comfortably with some of modern music copyright’s odd inventions, such as the so-called authorial protection of publishing rights. Like the bass lines of a thousand rap songs, the folk melodies and lyrics of the Anthology do not hew to 20th-century notions of authorship. It is music for the people and from the people, recorded not written down, born perhaps in the English or Scottish countryside of the 19th century, bred in Appalachia and other impoverished pockets of the United States. It’s music that seems carefully cut from another era and pasted back into the fabric of America, bent and strange: “Old Enoch, he lived to be three hundred and sixty five”; “In the days of eighteen and one, peg and awl”; “I asked them bring me my pistol, three rounds of ball”; “Oh death, where is thy sting?”

Smith illustrated the cover of the Anthology’s first edition with a picture of God tuning what he termed the Celestial Monochord. Perhaps the songs here don’t go as far back as Creation, but they do offer a kind of Rosetta stone for vernacular American music — vernacular art being what pop culture is after the marketing budgets are tapped: well-loved, well-worn trash. If the Anthology was meant to teach us the story of American music, Napster is the tool that could update that lesson for the present day.

Listen to what comes out of Napster’s simple searches — try typing in as a title just the word love — and it’s not hard to imagine it as the birth of a celestial jukebox filled with a selection of sounds limited only by the public’s will and a rapidly improving Internet architecture. Napster has cut through the glamour of video and the photograph and reacquainted us with music.

I’m continually amazed by what one is able to find even now, in a phase when Napster is just an outgrowth of one kid’s efforts to help further the effortless download of bad frat-rock. Turns out that that kid has invented 20th-century music’s greatest library and index: the Anthology of American Popular Music. One day, perhaps, as more people convert their favorite recordings into MP3s and add them to the directory, we’ll have the Anthology of All Music.

We are now being asked by modern entertainment conglomerates to hold off in accessing such a thing. We are being told to wait for them to prepare their own proprietary versions, limited most likely to each fiefdom’s narrowly dictated slate of fully owned songs. Yet now, theoretically at least, everything is in print, every record can be part of the public record, and that record can strive for perfection.

Why should we wait?

THE PRESENT

It’s July, midway through 2000. Something’s just begun, but we don’t know what it is.

Six months after visiting Erika, I’m driving through the heat of our century’s first summer toward Napster’s then-corporate headquarters in San Mateo, California, just south of San Francisco Bay (the company has since moved to nearby Redwood City). The billboards on this stretch of 101 tell the story of what has happened here since laid-back Northern California made its first impressions on ’60s pop culture. They echo that past (Excite.com: “Turn You On”), sarcastically mock old moral conventions (E*Trade: “Root of all evil . . . Can’t buy happiness . . . Blah blah blah”), and look upon the future like a carnivore licking its chops (Forbes.com: “Capitalism served fresh daily”). A hippie bumper sticker seen en route counters these billboards with a short riposte: “inner.com.”

Since its debut, the major labels have depicted Napster as a dark force for piracy emerging from Silicon Valley; the press has portrayed it as a rascally start-up leading a coup d’état to liberate music. These are images the company has embraced, adopting as its mascot what looks to be a cross between Satan and a clever kitten, and trotting into the spotlight the software’s initial architect, Shawn Fanning, a 19-year-old weight lifter, programmer and Northeastern University dropout. Fanning’s ubiquitous low-lidded baseball caps and his company’s sponsorship of a free Limp Bizkit summer tour seem sure signs that he’s sympathetic to the current teen vogue for self-consciously dumb mook rock. (“We weren’t hackers,” he insisted in a recent Spin piece about the company. “Absolutely not,” added Sean Parker, an early Napster employee. “We were white hats.”)

San Mateo, however, is not quite Silicon Valley. The environs do much to allay impressions that Napster is a force for either evil or good, unless you can deduce moral posture from the strip malls of a banal suburban street. The company is located in San Mateo’s Union Bank of California building, right across the street from Cheap Pete’s Picture Frame Factory Outlet.

Inside Napster headquarters, the place is the pluperfect start-up: The office carpets are stained. The walls are a smudged white. The only employees in sight appear to be male computer drones with mussed brown hair. The reception area smells a little like diapers. Inga, the staffing manager, is trying to schedule a haircut. No pirates.

I’m taken to the company conference room. There’s a gumball machine filled with gourmet jellybeans, and I’m told to eat as many as I wish. The magazine rack is telling. There are multiple issues of Fortune, BrandWeek, Hollywood Reporter, Fast Company, Business 2.0 and Red Herring. Spin is the only music magazine present, and it’s the issue with Napster on the cover.

After a month of requests, I’ve been offered a last-minute moment with Milt Olin, Napster’s new chief operating officer. After a couple of Fanning’s e-mailed zingers came out in the discovery phase of the RIAA’s suit, Napster’s teen wunderkind has been offered sparingly to the press. In one e-mail, quoted with relish in the RIAA’s motion for injunction, Fanning explained that users would be reluctant to provide the company personal information or “other sensitive data that might endanger them (especially since they are exchanging pirated music).” Whoops!

Olin enters and quickly establishes himself as a no-bullshit guy. His hair is sandy blond shot through white, and he’s of a comfortable weight. He’s virtually, perhaps consciously, styleless. He wears oval glasses, a light-blue button-up shirt, dark-blue pants and sensible black shoes. He throws his legs up on a chair and immediately begins to demonstrate a healthy, low-level paranoia: No audiotape is allowed. (Rule No. 1: No permanent record.) He answers my questions like a hostile witness. (Q: “Are you working more on the legal case or toward Napster’s future?” A: “That was a compound question. Yes and yes.”) He tells me what I should write about. (“The thing you could focus on is, When will an artist break via the Web?”) Then he begins to tell me about “first-mover advantage”; I begin to think about how much I’d like a jellybean.

I’m hastily disabused of the notion that Napster is some outsider force. Olin is a music-industry veteran. He was head of business affairs and legal at A&M Records until it was bought by Napster’s most vitriolic opponent, Universal, which shuttered the label in brutal fashion in January 1999, putting Olin out of a job. He formerly practiced law at Mitchell, Silberberg and Knupp LLP, the firm prosecuting the RIAA’s case. A few months back, Hank Barry — a friend, Napster’s interim CEO and a partner at the venture-capital firm that gave Napster $15 million to play with — called Olin up and asked him if he had any idea how seriously the music business was keeping an eye on the Internet. Says Olin, “It was like, shit, are you on the pot?” He soon started making the Monday-through-Friday commute to San Mateo from his home in Los Angeles.

RIAA vs. Napster is not a case of one side defending the fort and a band of interlopers charging the gates. The total lack of negotiations between the two sides is one sign that this is a standoff that traces its roots deep into the same old music business. Regardless of outcomes, it will most likely be the same old industry players grabbing at the money earned by artists.

Oh yes — Olin tells me approximately dick. (“I’ve been using the Internet since Prodigy, so longer than most of my contemporaries”; “To be honest, I don’t even know what patents we have”; “We’re first and foremost a community site . . .”)

As I leave the office, a series of bleeps emanates from my person. “You didn’t just tape this,” he says, gazing at me with the anxious look of someone just caught on record. “What’s that, a camera bag?” he asks, pointing to the old black satchel I brought into the interview. I open up the bag — I use it to carry around pens, pads, books and supplies — and take out my cell phone.

“Oh, I see,” he says, gesturing toward the anachronistic-looking bag. “It’s just an affectation.”

There is nothing in this office that harks back to my memory of records: “rawness, lust, disorder and youth.” I envision some vicious contracts.

With protagonists like this, just whom and what do you believe in?

THE FUTURE?

This is a story about music fans, music, and musicians becoming obsessed with the narcissistic glow of objects. It’s important that we recognize that it’s those three to which we owe our allegiance, not records.

It’s easy to blame the degradation of art, or at least the abuse of artists, on the forces of capital. But for the vast majority of the history of the world — from the grunts of cavemen to the dances, jigs and other social musics found on Harry Smith’s Anthology — music has been about community first and commerce second, if at all. The record business has done its best to invert that.

It’s not as if the communities that music thrives in have ceased to exist. In more recent times, this aspect of music has been referred to as “the scene,” and it’s continued to be a boon to music’s creation. In the ’60s, look no further than the psychedelic and blues-based rock & roll of San Francisco, or Memphis’ intense concentration of R&B and soul; in the ’70s, think of the session bands of Muscle Shoals or the arty downtown punk at CBGB in New York; in the ’80s, consider hip-hop’s birth from the burned-out husk of the Bronx, or indie rock’s trailblazing effort at establishing a circuit of grassroots tour stops across the nation; in the ’90s, contemplate trailer-park-bred death-metal and thrash or Chicago’s inbred, fiercely independent experimental-music scene. When they try to co-opt and sell to existing scenes such as these, the corporations that have been behind so much of our music this century perform something like a service.

But what these corporations have increasingly done is supplant the art they once served. I can guess why. Personalities crafted in the lab are simply easier to deal with, less capricious or explosive than real people, easier to throw away if they get out of hand. Think of the list of faux artists we’ve seen in the last 15 years, either birthed from invented scenes or brought to us as examples of sui generis corporate art. Consider the hair-metal of the late ’80s; the marketing of Vanilla Ice and MC Hammer as the embodiments of hip-hop; Milli Vanilli; the morphing of indie music into “alternative” rock; the Lolita-diva phenomenon of 1998-2000. These are well-crafted concepts; all have been quickly marked for obsolescence, to be tossed as soon as profit margins begin to decline.

It’s an alienating experience, even for the “real” musicians who make it into the system and manage to break into mass consciousness the old-fashioned way — by playing to people and having real fans.

Ahh, Metallica, the thrash-metal band that began its career playing to a small, dedicated audience of San Francisco burnouts. The group’s drummer, Lars Ulrich, recently put authentic rock-star alienation on display in a widely quoted statement to the press:

“I think it’s sad and pathetic that the only counterarguments people can come up with [for using file-sharing applications like Napster] is, ‘Like, don’t they have enough money?’ Yeah, we actually do have enough money; I have more money than I know what to do with for the rest of my fucking life, thank you very much for asking. The pool is 88 degrees 24 hours a day, the kid’s going to college . . . I’m fucking set! Now let’s get to the fucking issues. It’s so sad that the only counterargument is greed and money.” Set that gem to the Sturm und Drang of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, and you have the definition of ennui: the alienated albeit well-compensated modern rocker.

PREDICTIONS

Sometimes I envision things just getting more awful. I imagine the corporations that currently traffic in music like it was dish soap merely making the box more robust, turning “music” into something that can’t be copied as easily as a stereo track. We’ll listen to Britney or N’Sync in an immersive multimedia environment or be subject to interactive soft-porn pop, video games with more-developed soundtracks.

For the most part, though, I’m hopeful. I have faith that things will get better. In my optimistic future world, music corporations will take the initiative and focus their marketing and development savvy in ways that take advantage of the limitless distribution pipeline of the future. They’ll distribute myriad varieties of music by a far wider range of musicians than those that benefit from the system today; they’ll make it cheap or free; and they’ll discover and develop a wider range of musicians than anyone ever thought possible. None of those musicians will be able to heat the pool into perpetuity with their earnings, but neither will they hand over their songs into perpetuity to major record labels. In this golden age, the major labels will create the music destinations of the future; they’ll invent centralized gateways where consumers will find all the music they’d ever want.

But, naaaah, that’d never happen.

More likely we’ll witness the death of the alienated pop star. Musicians will come to better understand the benefits of independent entrepreneurship. They will follow the brave examples of musicians who have already learned to tend their own labels and their own careers. Be it Ani DiFranco and her Righteous Babe label, Fugazi and Dischord, Bad Religion and Epitaph, or Master P and No Limit, there are already successful artists who have proved that fans will go right to the source. A fringe benefit of this is that the musicians can stick to their idiosyncratic sensibilities and keep most of the money for themselves.

In a world where free recordings become ubiquitous, musicians may have to focus their energy on playing to people, the glamorous and the ugly. Whether it’s spinning records in a dance space or doing a residency at a scuzzy club, the social aspect of music will be reinvigorated. I would hope that musicians will forget the celebrity musician’s standard-issue pose of contempt and figure out how to connect with their audience so that it’s artists, not some major-label marketing department, who are reaching out to the awkward teens and nostalgic adults of the world.

The fact that weightless, wireless, intangible distribution will become increasingly prevalent should almost certainly destroy corporate control of recorded music’s distribution. This will have some very interesting secondary effects. Media outlets such as this one that make the public aware of product (i.e., music) will not be so beholden to informing people about the records now available in chain stores. A time may come when writers will be able to write about anything that strikes their fancy; readers will be able to access any of the music they read about by typing a search name into a silly little box. Eventually, readers will be drawn to an ever wider range of recommenders. Publications like this one will have no more control over people’s context than labels will over content, unless those publications can provide a context uninfluenced by the demands of advertisers. There will be many new checks and balances on money’s power over art.

When all of this happens, we will be living in a slightly more open world, controlled by desire and artistry rather than marketability and gatekeepers. With Napster and its ilk, that world is here. Now. (Unless, of course, the conglomerates that own the record companies gain control of our communication lines. I shudder to think what might happen if AOL-Time Warner make damn certain that we have access only to their own product.)

Will musicians make a substantive amount of money out of all this? My first response is, I don’t care. My second, more mannered response is that being an artist of any stripe is rarely a profitable venture. Artistry depends upon dreams, impracticalities that finance virtually never acknowledges. Period.

My third response is that I can’t imagine the situation getting any worse than it currently is. When I think of friends and acquaintances who make their “living” from music, I don’t see a lot of success stories. Comparing the endless mass of musicians unsigned and struggling to the infinitesimal fraction signed and still struggling to make ends meet, I can’t help think that a world with less powerful music corporations would be a better one.

Except for backup singers and session players, the musicians of the world don’t benefit from the record industry’s insistence on pushing a handful of superstars to worldwide prominence. When I hear the argument that music will end if record companies cease to exist, it truly hits home that our culture has gotten the words celebrity and artist and musician terribly mixed up.

Far more interesting than the potential for mercantilizing art in our new century is the possibility of what music might start to sound like if we stop trying so hard to cash in on it.

Once we do away with the manufactured concept of publishing rights — a truly ersatz notion in a world where most music is based on pure sonic stuff, not written notation — I fantasize that musicians will be free to realize the outer limits of recorded sound. They will sample and cut and copy and reinterpret the vast library of music that has been created in the last 100 years. Tone and beat, timbre and melody will take on strange new forms far beyond the odd sounds that have already been explored in music both popular (the assemblage of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band; the early pop-music collage of De La Soul and Beastie Boys, now verboten on major-label product; the thick dub of Lee “Scratch” Perry) and obscure (the coruscating tones of minimalist composers like Terry Riley; the fresh textures of Kyoto musician Aki Tsuyuko). Music will rejoin the long history of folk and vernacular art to which it belongs, instead of hewing to the false bylaws commerce has imposed upon it. It will be the iterative art that it yearns to be.

For song fans, there will still be people practicing the art, but they’ll be a hearty, dedicated bunch on a par with the classical musicians who dot the world — university- and conservatory-trained, subscription-symphony-supported. And along with the atomization of our attentions will come the death of what is likely the 20th century’s most enduring and significant contribution to art: the pop star. When else in history have humble, or not-so-humble, performers like Bob Dylan, the Beatles, Al Green — Michael Jackson? — had their art distributed in such a way that a single individual could instantly grab the attention of millions? How will anyone ever again be able to command the attention of the world?

I have exactly one guaranteed prediction: Lots of stuff is ending right now, but music ain’t in shit for danger. So, listener, while you’re stealing your music in the coming months, don’t think of contracts, just ask, “Does it treat us well?” Not do records treat us well, but does music?

And when you think of music, don’t think of the money some label might lose as you download its brand-new release. Think of some dead guy, maybe Robert Johnson, perhaps the greatest blues guitarist ever recorded, poisoned at 27 before the onset of fame. Try to better understand his conflicted and unclear feelings about the phonograph — You have broken my windin’ chain; Taken my lovin’; Give it to yo’ other man. Beatrice? — and wonder why so many of us have gotten locked into a debate that rests music’s fate on flimsy plastic vessels, a fidelity to high fidelity, a bunch of multinational corporations, an old lost love.

Originally published on LA Weekly on September 13, 2000.