Is rock music dead? A growing sentiment among music-industry cognoscenti is that consumers have lost interest in the genre, save for emo-crazed teenagers and obsessive indie hipsters. If you think that’s an exaggeration, witness today’s most high-profile major-label execs — e.g., Warner Bros.’ Lyor Cohen; Jay-Z and Antonio “LA” Reid at Island Def Jam — most of whom came out of hip-hop. Or, to put it in starker terms, when Rolling Stone needs an artist to pose as Jesus, it turns to Kanye West.

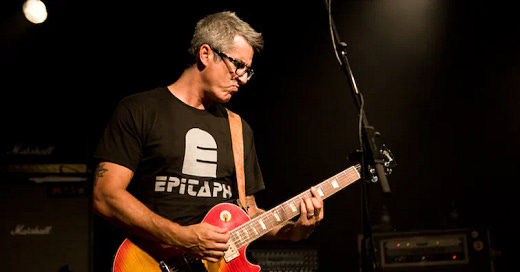

Someone has to keep the faith, and Brett Gurewitz may be that man.

“The problem is that rock is no longer a concise movement,” says the founder of the SoCal punk institutions Bad Religion and Epitaph Records. “The Beatles and the Stones and the Beach Boys are the trunk of the tree. But just because that tree has grown branches and grown bigger and bushier doesn’t mean the tree is dead.”

Gurewitz believes reports of the genre’s demise are exaggerated, citing the work of adventurous and ambitious young bands like the Arcade Fire and Animal Collective.

“You have to be an active music listener and consumer to get these bands,” he says. “It reminds me of Los Angeles. People come here and say, ‘Where is L.A.?’ because it’s this sprawling thing, but if you search around, you find all these pockets of goodness. Rock music just isn’t young anymore, and I think that’s what we’re grappling with. It’s difficult to wrap your head around the fact that the president of the United States is considerably younger than Mick Jagger.”

Now 43, Gurewitz began both his band and his label as a teenager in Woodland Hills, California. Twenty-five years later, it’s becoming increasingly clear that he’s already made a huge impact on American music. Bad Religion is a warhorse in the punk scene. A long-lasting group in a notoriously short-lived genre, it has released 13 albums, and, more importantly, the melodic hardcore sound it created in the ‘80s — layered guitars, harmonized vocals — provided a template for a generation of crossover punk groups, ranging from Green Day to Blink-182.

Gurewitz has been with the group on and off for the past two decades. His most notable absence came during the band’s major-label stint on Atlantic Records in the mid-’90s. Though he is a firm believer in independent music, he wasn’t really a conscientious objector. Rather, he was simultaneously grappling with personal demons and his business’ “overnight” success. In 1994, Epitaph put out both Rancid’s breakthrough, Let’s Go, and the Offspring’s Smash. The latter album would go on to sell more than 10 million copies, making it one of the best-selling punk records of all time. The two records, with help from Green Day’s Dookie, sparked a punk revival that’s still going strong. This ensured the label’s long-term viability and made Gurewitz a quick fortune. But as the label was blowing up in a good way, Gurewitz’s life was blowing up in a not-so-good way. He went through a bitter divorce; the Offspring left Epitaph in an ugly contract dispute (Rancid stuck with the label despite an intense bidding war among the majors). After seven years of sobriety, Gurewitz descended once again into cocaine and heroin addiction — a binge that lasted until 1997.

These days, Gurewitz is clean and sober, and once again active with Bad Religion, and the band is making some of the best-regarded music of its career. However, it’s become increasingly clear that Gurewitz’s real legacy will be the aptly named Epitaph.

Begun with the modest goal of releasing his band’s 7-inch singles, today it is an umbrella organization for four labels. Together, they release about one new album per week. The mothership, Epitaph, has expanded beyond punk to release underground hip-hop (Minneapolis’ Atmosphere, Northern California’s Blackalicious); Hellcat focuses on ska and other street-punk styles; and the Swedish-based Burning Heart has found a U.S. audience for driving garage-rock groups like the Hives and Turbonegro. The jewel in the crown, though, is ANTI-, an eclectic label founded in 1999, it focuses on songwriters with strong roots in blues, Americana and R&B.

In a previous interview, Gurewitz explained ANTI-’s origins: “There was a moment when I said, punk isn’t all I listen to, and I can’t put out only punk forever, so I made a conscious decision to start a label for stuff that wasn’t part of that genre. I first talked to Tom [Waits] in the mid-’90s. But at the time, I could only put out punk on Epitaph. The punk and indie scenes were much more reactionary than they are now. It’s one thing I’ve always found strange. Punk rock is this movement of weirdos and misfits, and yet, with the exception of a couple of pockets — like Los Angeles in the late ‘70s, which was very artistic — you’ve always had to fit in. So I decided to branch off.”

Indeed, that’s what ANTI- did, quickly assembling an impressive roster of iconic songwriters from this generation (Elliott Smith, Neko Case, Jolie Holland) and yesteryear (Merle Haggard, Solomon Burke, Bette LaVette). It’s also given a shot in the arm to the careers of artists like Waits, Joe Strummer, Nick Cave, and Daniel Lanois.

“By definition, counterculture and alternative music can’t survive success,” says Gurewitz. “What I’ve done is persevere and reinvent myself, and keep going in a way that has some dignity.”

Though his understanding of music has grown far beyond even rock & roll, on many levels his attitude remains as punk as they come: “Now it’s gotten to the point where I’ll put out whatever the fuck I want on any of my labels. Maybe I’m just past the point of caring what some 16-year-old wants to flame me about on a message board.”

Originally published in LA Weekly April 19, 2006.