Robert Stone’s friends are throwing him a farewell party. They’re in Los Angeles in the summer of ’69. Balloons are everywhere, but these are for inhaling nitrous oxide — that’s laughing gas in plain English — a substance later generations will refer to as “hippie crack.” The actual locale is lost to the mists of time, but given the circumstances and the time frame, let’s guess they’re in a posh Laurel Canyon bungalow, or maybe an apartment in the Hollywood flats, a seedy place with a frisson of glamour.

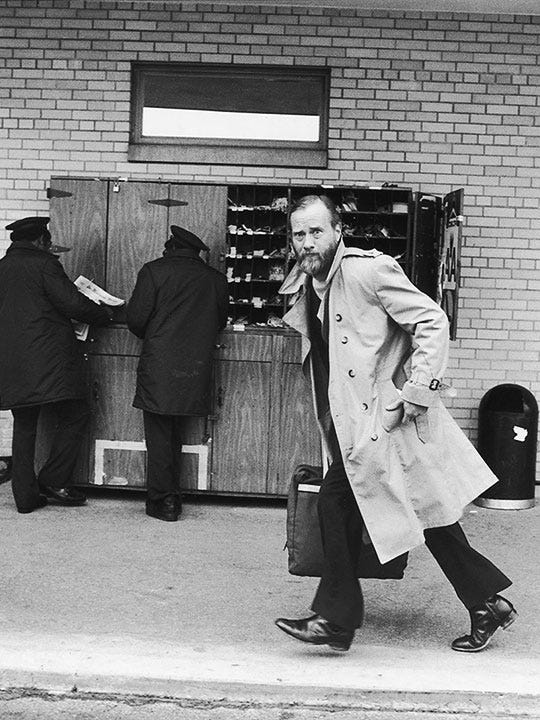

A little-known, 30-something fiction writer, Stone is in L.A. thanks to the good graces of progressive, socially conscious actor/director Paul Newman, who is adapting the author’s first book (A Hall of Mirrors) into a movie (WUSA) so mediocre, Stone will lament its “general badness.” That same summer Charles Manson’s disciples will visit two Southern California homes, murdering six and writing on the walls with human blood.

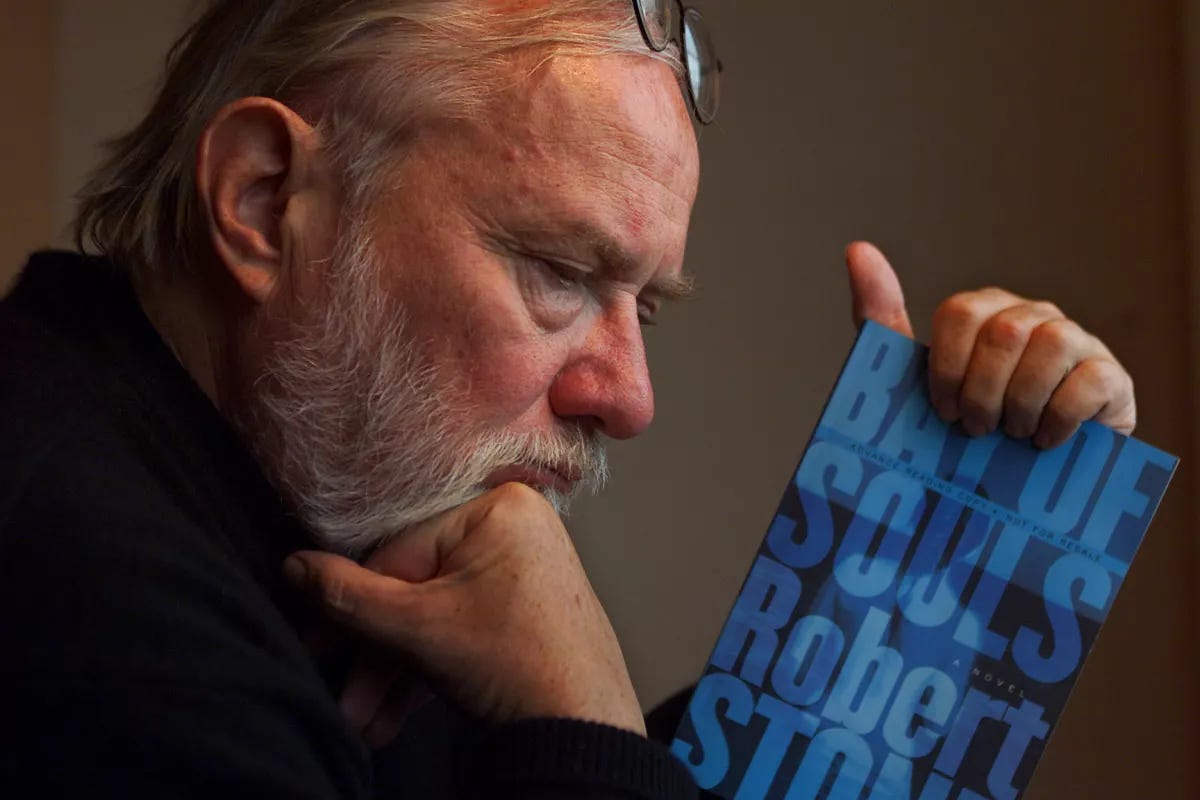

But, still, what a celebration they were having! To understand what it was like to live through 1969 we need only refer to Stone’s meticulous witness, Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties, in which he writes about the attendees’ children who got to play along:

And the kids so liked the balloons, and of course they liked the gas too, taking the gas from the balloons. How this happened, what happened next, nobody is sure because everybody was ripped and fighting greedily over the gas, and the children were fighting greedily over the gas too. So to square it, even-steven it, we declared, we the adult authority, come on, kids, just one balloon’s worth to a kid.

When, would you believe, this one little tyke made this snarky face right at me and said ha ha or hee hee or some shit, “These aren’t balloons! They’re condoms!” And by the spirit of William James, they were condoms. We’d been getting loaded watching small innocent children sucking gas from condoms.

As one of Stone’s most treasured influences, Joseph Conrad, once wrote, The horror, the horror.

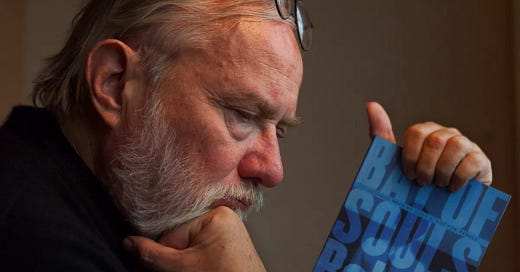

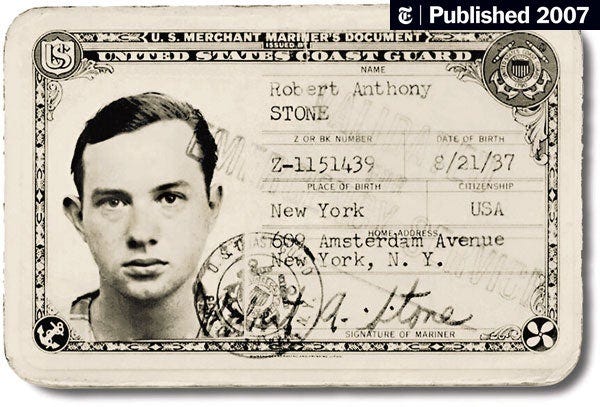

Today, Stone is a 69-year-old, much-lauded novelist. Though he always avoided vogues and never became an overexposed literary celebrity, a number of his novels have been best-sellers; his 1974 National Book Award winner, Dog Soldiers, is a staple of university surveys on post–World War II fiction; his work is regularly excerpted in The New Yorker; and, privately, he speaks of invitations to dinner parties alongside Salman Rushdie and Paul Auster. But, reminiscences like the one above make it clear that his path to the upper echelon of literary success was hardly straightforward.

Thanks in no small part to the pronouncements of critics, peers and close friends, Stone is viewed as one of the darker figures in the literary pantheon. As a younger man, he was a frequent visitor and presence at the La Honda, California, compound of Ken Kesey, author of the perennial best-seller One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. It was an extreme scene, one that gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson — no stranger to extremity — referred to as “the world capital of madness.” (Thompson was spending time there meeting and documenting the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, another group which frequented Kesey’s virtual commune.) Yet of all the drug-enhanced personalities in La Honda, Stone is the one Kesey labeled “a professional paranoid, someone who sees sinister forces behind every Oreo cookie.”

Take these descriptions with a grain of salt — Thompson’s metier was overstatement; Kesey loved to turn his friends into caricatures — but such accounts are the bedrock of Stone’s reputation. He is depicted as a living, breathing example of the loners and outcasts in his fiction; a 1997 Salon interview, for example, appeared under the headline “The Apostle of the Strung-Out.”

Before meeting Stone, one is steeled for a visit to the heart of darkness or at least to the lair of a hippie-era burnout. But then he opens the door to his apartment in the Yorkville section of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a quiet neighborhood rife with plumbing-repair stores, hobby shops and clothing retailers that happily disregard fashion.

Stone greets me with a smile — possibly warm, definitely courteous. There is a glint of recognition. I first met him in the late ’90s, as a student in one of his writing seminars; I last visited him about four years ago. His handshake feels stronger than it once did. His face seems brighter, and his features more animated. 2002 marked the final chapter in a nomadic, 30-year teaching career that included short stints at some of America’s best schools (Princeton, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, UC Irvine and UC San Diego) and, finally, an 11-year run at Yale. Retirement seems to suit him.

It’s easy to be impressed by Stone’s gravitas. He is rough-skinned and white-haired, and wears a longish beard that cascades off his face like a blizzard before it comes to a well-groomed point. He’s an imposing figure, yet one soft to the touch.

Janice, his wife of 47 years, offers coffee. Stone asks for a nonalcoholic beer.

“An experiment in sobriety,” he says.

I’m uncertain if this is intended as a joke, or a revealing detail. Certainly it was a nod toward the old cliche: the substance-abusing novelist tippling in the late afternoon.

Janice hands him a nonalcoholic beer.

***

ALEC HANLEY BEMIS: In Prime Green, you set up this dichotomy of people in the ’60s as being either on the bus or off the bus, repeating the famous line. But in the memoir you are halfway on the bus. How deep was your participation?

ROBERT STONE: I was, in a way, in the right place at the right time, because I got the Stegner Fellowship to Stanford in 1962. So I fell into this group of people, most of whom were grad students. They were the dope smokers and the bohemians if such a concept still existed in 1962. I met Kesey, and Kesey was the master of the revels. He was also working as an orderly at the hospital, so he was the guy who provided us with various kinds of psychedelics, which I had run into actually in ’59 in New York, but not quite in the same sense. There was a place in the East Village in 1959 that sold peyote buttons, and the guy that ran it was a follower of Ayn Rand. So I was on the bus. I did not cross the country on the bus, but I saw it when it started, and it pulled up in front of my house in New York. My daughter has never forgotten going down the stairs holding the hand of a man who was painted completely green.

AHB: Did you feel like you fell between the cracks of the two most famous Bohemias? That you were part of this middle generation?

STONE: I used to say I felt like I went to a party in ’63, and the party followed me out the door and filled the world. By ’67 it was all over. The Summer of Love killed it. I went to Europe for four years. It certainly happened in London, and Kesey came over there for a little while, but it was entirely different. My world consisted not of any kind of mass movement, but of a small circle of friends, as the song says. We had so many adventures at different times together in the years before the mass youth bohemia was created. And I guess that was all okay, but it was like anything else that gets watered down.

When I first knew the guys who were the Grateful Dead they were students at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and they used to wear their suits to the train. So it’s a mystery to me what happened. I mean, I know what the operative forces that created the ’60s at the beginning were. Part of it was the civil rights movement and its various spiritual components. Some of it was the coming of age of the red-diaper babies, of which there were many in California. A lot of it was a continuation of what was happening in the ’50s, because the end of the ’50s was pretty good too.

I got out of the service in ’58, and I was working for the Daily News. Janice was a guidette in the RCA Building, but she would also change her uniform and put on black stockings and work in espresso bars; she worked in the Figaro and in the Seven Arts, places that Kerouac and Ginsberg and Gregory Corso and all these people went to. So between the idealism of the civil rights movement and the growth of pacifism as the war increased, politics were being revived by a new generation. The music and so on: People had suddenly abandoned the classical music they had listened to and started listening to gospel. Drugs were certainly part of it. People were smoking pot. We were very snobbish about our pot smoking. People used to ask each other, if they were bringing someone, “Are they cool?” The question meaning, would they be shocked if someone smoked a joint. It’s not like we were taking acid day and night — it was occasional. But we kind of identified with it. It was one of our badges of identity. And we were really doing it in imitation of the French symbolist poets.

AHB: Do you think your relationship with the later ’60s matched Kerouac’s or Cassady’s relationship to the later end of bohemia and the Beat movement?

STONE: Yes, when it became a mass phenomenon, when it became the youth culture, it sort of lost all meaning to me. Because, for one thing, I came from a background that was not particularly intellectual. I went to Catholic schools in New York. I went into the service when I was 17. I mean, you didn’t get much of an opportunity to talk literature. I got to Stanford and you could talk about books, you could talk about music, you could talk about all this stuff, and I was very attracted to the life of the spirit and the life of the mind because it was a luxury I had never been able to indulge. So when I came on it, one of the things I really valued in addition to the pot and the parties was the society of culturally sophisticated people. And that’s why I lost interest when it became a mass youth culture.

AHB: When did you see that beginning?

STONE: By the middle ’60s, a lot of people were hanging out, especially when Kesey moved to La Honda and he had a scene out there that attracted a lot of people who drifted in and out, and Kesey was a guy who never really turned anybody away, so there were sort of more hangers on, and fewer of the old gang.

AHB: As a writer, Kesey wasn’t that prolific as people expected after his first burst; instead he developed his own persona and his own thing. Was this a general trend among the people that surrounded you at that time? Did Kesey have regrets about that?

STONE: He never expressed any regrets. That wasn’t what he was like. He was a pusher of the envelope. He wanted to somehow change the world, and he wanted to do it himself. In some ways he tried to inhabit his own books, he tried to be his own books, he tried to be McMurphy from Cuckoo’s Nest. It was as if he somehow felt that if he pushed the right button he could effect great change in the world. I never really believed that. I was not a cultural revolutionary in that sense. I never believed that the larger world was going to be anything but what it is. I also think Ken resisted the writing life. I said somewhere that most writers that aren’t Hemingway spend more time staying awake in quiet rooms than they do shooting lions, and I think the loneliness got to him as it gets to a lot of people. You spend a lot of time getting into intense emotional states by yourself, and I think that’s why many writers tend to substance-abuse. They tend to drink; they tend to get stoned. It’s a way of ending a day. And I think this solitary thing was really not for him. He was an athlete. He really wanted everything fast and furious.

AHB: Unlike Kesey, you were relatively prolific. Did you see how he was dealing with his career and take that as a corrective? Or were you looking at someone like Kerouac?

STONE: I never thought much of Kerouac’s work. Actually Kerouac, when I knew him, was a very difficult character and not a very pleasant character either, because he was gone into booze and gone into this right-wing bullshit. The last time I saw him, or close to the last time, was at a party in New York after Cassady had driven the bus cross-country. And Kerouac was very jealous of Cassady’s attachment to this new generation, who he referred to as “surfers.” He was a very sentimental guy and a very sensitive guy, and that sentimentality turned into bitterness. You know he got thrown off the [William F.] Buckley show for anti-Semitic remarks. He wasn’t a very easy person to get on with. And he didn’t like people who were much younger than he was.

AHB: But did you look at such examples and say, This is not the way to go, or I’m going to go this other way? Or is it just your personality that you could deal better with the lonely rooms?

STONE: I had trouble with lonely rooms, but I never wanted to do anything else really. Every once in a while I would do some journalism, and that would keep me going. But I had trouble with the solitude. Everybody does who is subject to their own moods; it’s hard to fight your way out of them. You’ve got to exercise, you’ve got to keep yourself in shape. All of this is difficult when you don’t have colleagues and contacts, but this is what I wanted to do, so I did it. Every time I think of a novel it seems so hard, I can’t imagine starting again. But I kept at it. I think I would have produced more if I wasn’t as lazy and perfectionistic. It’s a bad combination.

As for Kesey, he had published two books by the time I got to know him. As a writer, I didn’t put myself in the same league. I was an unpublished writer. I had the beginnings of a novel that I was carrying around. It never occurred to me I would compete with him. He seemed able to do it all. He had so much energy. It certainly never occurred to me that he was going to stop writing.

AHB: The main events of Prime Green take place in California. There’s talk of Los Angeles as a location and San Francisco as a location, but do you have a concept of California as integral to the ‘60s?

STONE: Oh, absolutely, because that was the first time I saw California, and Northern California in 1962 was a great paradise. Where Silicon Valley is now was all orchards and grazing Herefords, and there were all these bungalows. Graduate students lived in a little rural lane that is now cul de sac million-dollar houses. So it was inexpensive, it was sweet, and if you came from New York everybody seemed really easygoing. Life was easy and San Francisco was this little jewel of a city. It was very, very pleasant.

AHB: Did California occupy as large a space in the public imagination then as it did afterward?

STONE: I don’t think so. California suddenly burst out with this cultural explosion. Things were going on in other places to a degree — around Harvard there was Leary, for instance — but I think it was Look magazine that had a picture of a couple of friends of mine getting married outside at one of these, what they used to call hippie weddings. That was on the cover of Look. So it was linked to California, certainly to my mind, but also beyond my mind. More to Northern California than to L.A., because L.A. was always more of a bullshit-walks kind of place.

AHB: Have you spent considerable time out there since then? I know you taught at UCSD in the ‘70s.

STONE: I spent all last summer at Santa Monica.

AHB: Just for travels?

STONE: Yeah, just for travels and I occasionally do a little bit of television work, and a couple of projects. So I spent the summer out there.

AHB: Have you done television that you attach your name to?

STONE: No, I’ve never had a credit, except for the movie adaptations of my books, which I’ve kind of disowned. But I don’t have any television credits. I don’t work for credit.

AHB: Now that there’s a generation of kids whose parents didn’t grow up in the ’60s, do you see kids who have a different perspective on that time, or who are dealing with those freedoms differently? Maybe those last college classes you taught?

STONE: Well, there is really now a tremendous conformity in terms of style and wearing the right clothes and having the right watch, and also in having the right attitudes. We were probably enforcing something like that ourselves although we didn’t expect it from everybody. But I think there is now a kind of moralizing, and I mean moralizing as opposed to moral consciousness. A conformity of attitudes that seems a little dolorous.

AHB: I’ve heard it said that this is the first generation that’s more conservative than its parents.

STONE: It certainly is in style, and in attitude. This generation is more conservative than the one before, I’m sure, and of course it’s extremely materialistic, in a way that it wasn’t nearly as much. People who were making a lot of money in the ’60s were kind of ashamed of it. Poverty was really kind of valued, and today is a very materialistic and really cynical era, in spite of the moralism. I don’t know what the change is in terms of kids growing up with all this technology. It seems like information gets circulated very quickly and somewhat superficially.

AHB: What has your teaching meant to your career and to your life?

STONE: What it gave me the chance to do was to preach, for lack of a better word, and to express what I felt about literature and what I felt about life in general. I also got to know what was going on with generations of people over a long period of time. One of the things that surprised me was how similar each generation was on a certain basic level. There were fewer changes, central changes, in young people, than I would have expected, for all the changes in style.

So it was interesting, and I sort of continued my education. I worked in libraries, I took books out, as an autodidact I was always curious. It provided a certain order in my life which I needed, a certain structure to the week. I think I would have been too loose without teaching. I feel as if I was effective at it, and I also felt that I was doing something for the world. I feel like I’m doing that with writing too — because I have some ideals about the function of insight and the function of writing, and I think of that as something useful. But I certainly thought of teaching as something beneficial and worthwhile. I like to think I was making my little contribution to the general consciousness.

***

When, as a student, I first met Robert Stone, I was ignorant of his place in contemporary literature. In fact, like most adolescents of our media-saturated age, I was largely unaware of literature — at least any that hadn’t been adapted or repackaged in a medium targeted toward youth culture: television, the movies. Still, the stories of his participation in real history couldn’t help but inspire a little awe. I would learn from him, study by his side. He would be a mentor or — to steal an image from film — a bookish Yoda instructing me in the way of the countercultural Force.

Stone, unfortunately, didn’t appreciate my quintessentially modern affect — a youthful, rebellious posture combined with little interest in the hard work of documenting those feelings on the page. Creative-writing classes are supposed to be easy, but in that era of rampant grade inflation, he was the only professor to award me a gentleman’s C.

I didn’t hold it against him. In retrospect, I’d say I even welcomed the dose of reality — and it’s one I’ve continued to receive, in small amounts, over the years. I remember one visit to his office on Yale’s campus. Barely used, it held few personal effects — a pile of books, a poster of Pieter Bruegel’s famous painting of the Tower of Babel. (As the story goes, it depicts a structure humanity built in an effort to reach heaven. The story ends when God — of course! — knocks down the structure.)

I was a recent graduate smack-dab in my middle 20s. What was his advice to this former pupil when asked, “What should someone do if they’re interested in a creative life?”

He was diffident at first, perhaps wondering why anyone would look to him for wisdom. But he looked the part. When I first met him, he was 58, and he could have passed for someone 20 years older, or ageless — in a word, Yoda.

Finally, he turned to me — no chewing of the literary cud — and this is what he said: “You should do whatever the hell you want.”

Originally published in LA Weekly on January 17, 2007.