The Soft Revolution

Today’s folk songs are being sung — very quietly — by a generation that’s had it with sex and drugs and doing it in the road

Today’s folk songs are being sung — very quietly — by a generation that’s had it with sex and drugs and doing it in the road

By Alec Hanley Bemis, Special to The Los Angeles Times

NEW YORK CITY’S Webster Hall was filled to capacity for the Plug awards, a celebration of the independent music community and its latest critical darlings. The performers booked for the evening were a diverse representation of the independent scene—so diverse, in fact, that you’d have been hard-pressed to explain the music they made to anyone who’d checked out during pop music’s two-decade evolution into a million subdivisions and subgenres. They included turntablist Rjd2, the thrash metal band Dillinger Escape Plan, underground rapper Aesop Rock, strident spoken-word artist Saul Williams, and the modish pop-punk group Ted Leo & the Pharmacists.

It had taken a leap of imagination by the organizers to envision the audiences for these artists being brought together in one venue. But the artists did have one thing in common: noise. The performances were theatrical, aggressive, demanding of attention. Which has long been the stereotype of the music of youth, and indeed the entire culture of youth. The kids have short. Attention. Spans. They-want-quick-cut-edits. They like their entertainment loud fast out-oF-cOnTRol!

There’s a problem with this theory.

Although the average age of the audience at the Plug awards was probably 25, the evening’s most eagerly anticipated performer was a folk singer named Sufjan Stevens. Added to the bill at the last minute, he sang two songs, and offered a break from all the noise. His style was in keeping with the thrift-store chic of underground pop—mussed brown hair, blue jeans, a sleeveless winter vest. His affect, though, couldn’t have been more different. Where the other artists leaped and lunged in an attempt to pump up the audience, Stevens was beatific. Lit by a crepuscular spotlight, he played an acoustic guitar and was accompanied by a single backup singer, who stood to one side with her arms crossed modestly behind her back. They performed before a projection of a rolling blue sky filled with puffy white clouds.

The first song was “Casimir Pulaski Day.” Nominally about a minor holiday for a Polish-born Revolutionary War general, it’s actually about a young man lingering over the hospital bed of his beloved, a woman afflicted with osteosarcoma, cancer of the bone. The title simply pinpoints the day on which the song’s most critical events unfold. At first it was difficult to make out the lyrics over the chatter of the crowd—doubly so because Stevens delivered them in a kind of whispered, melodic narration.

All the glory that the Lord has made

And the complications you could do without

When I kissed you on the mouth

Those who could make out the words were confused—first by the earnest shout-out to a higher power, then by its juxtaposition with a kiss, and finally by the twist that followed.

Tuesday night at the Bible study

We lift our hands and pray over your body

But nothing ever happens

This wasn’t just a song being sung, but a story being told, full of specific, writerly details. Early on the narrator brings the girl a gift of a flowerlike herb called goldenrod, placing the season as late summer. By early spring, she succumbs to the cancer that’s invaded her bones, and on the day she dies, a cardinal crashes into her hospital window.

It was a song marked by faith and doubt. It was quiet and reverent. It would be an understatement to call the setting and tone atypical of indie rock. (Scruffy musicians don’t often brag about attending Bible study.) What was most interesting, however, was Stevens’ take on religion, and how atypical it seemed in these religiously righteous times.

His set could be heard as a series of stark questions for the unquestioning: What if a few more Christian voices had declared that Terri Schiavo’s deathbed struggle was not something to be politicized? What if the Catholic Church were to acknowledge that romantic love and faith are not mutually exclusive? What if those who believe in God felt free to wonder what he hath wrought?

What if American culture were afflicted with an insidious cancer in its very bones, and a hundred prayers couldn’t fix it?

***

SUFJAN Stevens is one of underground music’s oddest recent success stories—a self-avowed Christian in a scene that is irreligious to its core; a singer-songwriter who graduated from the New School’s MFA fiction workshop; a performer with more affinity for Paul Simon’s dulcet tones and contemporary classical music’s sonic wallpaper than Bob Dylan’s incisive wit and punk’s snarling attitude. In an interview a few weeks after his performance at the Plug awards, near his home in Brooklyn’s Ditmas Park neighborhood, he is an even more striking figure. Close up you can see his clear hazel eyes and the Madonna-esque gap between his two front teeth; you can feel the energy he emits, at once confident and reserved, solicitous and bristling.

Stevens resists discussing his life in a way that might compromise what he believes in. “My faith informs what I’m doing. It’s really the core of what I’m doing in a lot of ways,” he says. “But the language of faith is a problem for me, and I try to avoid it at all costs. You could say that I have a mind for eternal things, for supernatural things, and things of mystery. I’m more comfortable with using those terms because they can be used without controlling or stigmatizing anyone.”

More on that in a moment. First it should be noted that Stevens, his faith and his particular way of expressing it are not all that odd these days. A growing number of young singer-songwriters are using a similar tool set—quiet voices, acoustic instruments and a fondness for mystery. The most prominent among them are Iron & Wine (a.k.a. Sam Beam), Antony and the Johnsons, Joanna Newsom, Devendra Banhart, and Bright Eyes (a.k.a. Conor Oberst). This isn’t the latest local scene; these artists are from Manhattan and Omaha, Miami and Nevada City, Calif. Some have been performing for years, some are just starting their careers, yet all have surfaced in the mainstream press in the past year.

Unlike many critical darlings, these artists are also making a commercial splash. Bright Eyes’ “I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning” has sold 300,000 copies, perhaps on pace to join an elite group of gold-certified indie releases, signifying a half-million sales. Iron & Wine’s latest album for Sub Pop, the label that championed grunge in the early ’90s, has sold more than 100,000 copies. Stevens’ success is particularly impressive, given its context. He still records for his own Asthmatic Kitty label, which he runs with the help of his stepfather and a friend. It’s probably the largest entertainment company in Lander, Wyo. (population 7,000), but that’s a long way from Los Angeles, so it was a shock when his latest album, “Illinois,” debuted at No. 1 on Billboard’s Heatseekers chart in July.

Most of these artists have been lumped into the so-called “avant-folk” or “freak-folk” genre, or, as it’s known in the United Kingdom, “the new weird America,” a phrase cribbed from “Invisible Republic,” Greil Marcus’ acclaimed 1997 book on Bob Dylan’s “secret” basement tapes. (Marcus referred to the American folk music of the ’20s and ’30s that informed these recordings as “old, weird America,” and recent editions of the book have been retitled as such.) I prefer the more descriptive and less loaded term “quiet music,” because while these artists are uniformly subdued, few hew to the standards of ol’ timey American folk. Sure, Stevens likes banjo and clean guitars, but his technique recalls that of contemporary classical musicians such as Philip Glass and Steve Reich, or the French-British avant-pop band Stereolab. Newsom, a harp prodigy, and Beam, a guitarist, both have an affection for the plinking melodies and polyrhythms of Mali. Finally, there is an artfulness to this music, a self-conscious pretension, that belies the back-to-basics formula of previous folk revivals.

At their most obvious, though, these artists do subscribe to folk’s long-established role as a medium of protest. Take Oberst’s song “When the President Talks to God,” which he performed on “The Tonight Show” in early May, decked out in a red Western-style shirt and big black cowboy hat. Originally released as a free download on Apple’s iTunes Music Store to promote two simultaneously released Bright Eyes CDs, it blatantly questions the conservative religious agenda behind George Bush’s America.

When the president talks to God,

Are the consonants all hard or soft?

Is he resolute, all down the line?

Is every issue black or white?

Does what God say ever change his mind,

When the president talks to God?

When the president talks to God,

Does he fake that drawl or merely nod?

Agree which convicts should be killed?

Where prisons should be built and filled?

Which voter fraud must be concealed,

When the president talks to God?

Oberst fumes at how faith has been transformed from a private act of devotion into the stuff of mega-churches, media circuses and public posturing. It’s a sentiment just as angry as those expressed by the punk rock bands whose popularity surged in the early ’80s during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, yet musically, his sound bears closer resemblance to the spare, bluesy “finger-pointing” songs on Bob Dylan’s political albums from the ’60s. Finally, it’s this quietness that’s more to the point than Oberst’s lyrics.

We’re living in a particularly loud moment in this country’s history, with home-front wars being waged in the name of religion, culture and partisan politics. The dominant political party is claiming to carry the banner for old-fashioned, conservative American values, yet it does so in a fire-and-brimstone declamatory style that makes punk rock’s rage seem like a Hallmark card. There are various ways to cope with this kind of noise. Humor is one of them. (Thus the popularity of parodic news outlets such as The Onion or Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart.”) Splendid isolation is another. It’s no coincidence that the most profound artists in the Soft Revolution are as concerned with offering a respite from what’s happening to this country as with protesting it.

***

ENCOUNTERING Antony Hegarty in his Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea, the famously gay art capital, is to be instantly immersed in his gossipy, gender-bent, confident-then-crumbling world, one familiar to fans of his mentor in pop music, Lou Reed. (His wider circle of influences ranges from Japanese butoh dancer Kazuo Ohno to Australian performance artist and dance club icon Leigh Bowery.)

Within minutes of our first meeting, Hegarty runs into the street, gallantly chasing the taxicab in which I’ve left my cellphone. Later, in a cafe, he leans over his cup of tea and asks if I am “a fag.” (“I love to ask that question,” he says with a giggle.) Yet none of his flamboyant gestures are aggressive or discomfiting. They’re more like an effort to forge some kind of intimacy, or to draw me into his consciousness.

Hegarty, who uses only his first name professionally, is dressed down in corduroy pants, with a hooded sweatshirt pulled over his pale blond hair. He is tall but soft, and the combination makes him appear vulnerable and slightly freakish—like an albino or a boy in a bubble, lacking the immunities it takes to survive in this world. Apropos of this image, he launches into a self-described rant about the perils of our age: “You can’t watch television anymore, it’s so toxic. I watch commercials for five minutes and can be completely spiritually annihilated. You’re just getting lied to by companies that are being paid to lie to you, and it’s sickening to the very core. There’s nothing to be salvaged.” He says his fans have a very specific relationship to the medium. “A lot of the people listening to me are these new groups of kids who have unplugged from the main avenues of culture, and are creating new local culture. Very wisely, they are turning off the dominant streams.”

This rant seems clichéd, until he turns his critique toward a less expected target. After a momentary pause, Hegarty reflects on the installations of Damien Hirst, the archetypal Young British Artist of the ’90s, coldly describing his work as “chopping a cow into three parts and putting it in formaldehyde and forcing everyone to be dead, to feel more dead.”

“Look, I’m not really a peddler of light,” Hegarty admits. “My thing is still pretty dark. But I’m always seeking transformation. The ’90s were so apocalyptic, and I was so there with apocalypse, but I’m so not there right now. Now I’m trying to nurture something that’s living, that can flower, that’s emotionally alive. I think the most forward-thinking thing an artist can do is try to envision solutions. And better possibilities.”

Hegarty’s popularity has surged this year, in spite of his admittedly challenging subject matter—often edgy sex, homosexuality or transgenderism. (In “Fistful of Love,” a kind of paean to masochism, he sings, “I feel your fists / And I know it’s out of love”; another lyric, which seems almost humorous in print, goes, “My lady story / Is one of annihilation / My lady story / Is one of breast amputation.”) What’s important to realize, though, is that unlike previous gender-bending performers, from Alice Cooper to Marilyn Manson, it’s not the shock value that gets your attention, it’s a quest for better possibilities. It’s the magnetic pull of a singer who, with a few piano ballads, some horn arrangements and his tender voice, makes scandalous sexual practices something to consider on a decidedly human scale. In Hegarty’s music, these subjects are neither indecent nor provocative—they are simply one aspect of a fully considered life, inspiring shame and joy in equal measure. After hearing him, you will surely wonder how it’s possible to legislate against that.

***

HEGARTY’S muse is more extreme than most. The other artists I’ve gathered under this rubric of quiet music tend to espouse fairly traditional family values, and are as likely to model their lives on their parents’ beliefs as they are to rebel against them. That’s not to say that their parents are particularly traditional.

Devendra Banhart is a case in point. Born in Texas, raised in Caracas, Venezuela, and Malibu’s Encinal Canyon, he briefly attended the San Francisco Art Institute before setting out as a self-styled hobo/minstrel, wandering the country until his music career magically took flight. (In fact, Banhart has been fairly calculating in placing himself at the center of the freak-folk movement. Last summer, for example, he curated a compilation album, “The Golden Apples of the Sun,” which included many of his fellow folk singers and was released on an imprint of Arthur, a popular underground newspaper based in Los Angeles and distributed nationwide.)

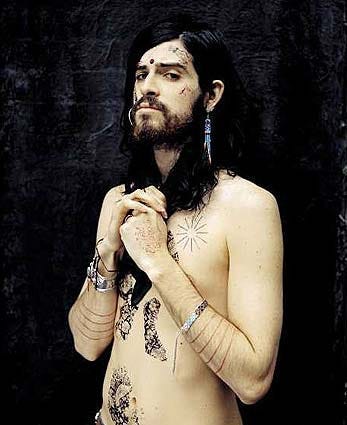

A handsome, skinny, unshaven young man with long black hair and an olive complexion, Banhart could almost pass for Middle Eastern, and his name, which means “king of gods” in Hindi, is not a pseudonym. Rather, it was suggested by Prem Rawat, a controversial spiritual leader his parents followed when he was a boy. They were seekers, albeit ones with a good sense of humor. Banhart claims his middle name is Obi, and that it comes from the Jedi master played by Alec Guinness in the original “Star Wars” films.

Some have suggested that this version of his life story finds him indulging in Dylanesque self-mythologizing, but his respect for the core beliefs of his parents is incontrovertible. “If there’s anyone we relate to, it’s our moms and dads,” he says. “It’s older hippies, people into Eastern philosophies and New Age, in the sense that if you look at the seed of every religion, it’s all the same, so let’s start our own vague one based on love and peace and unity and going within.”

In recent photographs, Banhart has appeared with a black bindi on his forehead, a mark typically worn by Hindu women, but if one were to divine his faith from listening to his lyrics, it would resemble an animistic fantasy land filled with “dancing crabs,” “yellow spiders,” “sexy pigs” and “happy squids.” The way his music sounds—acoustic and hypnotic, warm and approachable—is a far better indicator of his spirituality. In “This Is the Way,” he sings: “This is the sound that swims inside me / That circle sound is what surrounds me / This is the land that grows around me.” Indeed, it sounds as if he’s strumming circles in the air, as if playing itself were a devotional act. And in a sense it is, insofar as he believes deeply in music’s ability to act as a balm to the soul, to better the world of which it is an integral part.

One of Banhart’s favorite things to do during interviews is to name-drop long and baffling lists of his friends’ musical projects. In one such eruption he cites Six Organs of Admittance, Vetiver, White Rainbow, Little Wings, Yacht and Yume Bitsu in quick succession. His intentions, though, seem far from mercenary. “Their records are good for me,” he explains quite tenderly, “and I’m just personally going to be honest, they’re good for you too. I can say that they are, I’m sure they are. I’m sure they are.”

***

THE singer-songwriters of the Soft Revolution are part of the first generation to come of age in a world where nothing was forbidden. They are the anti-Victorians. For these kids—and in this day and age, even 30-year-olds can be referred to as kids—the bras have already been burned, rock ’n’ roll is the soundtrack to a car commercial and the ’60s are no longer thought of as a revolution in consciousness. Rather, the ’60s are something from a history text or an ad in Rolling Stone, and rebellion is a canned message you can get your fill of by watching five minutes of MTV. Many members of this generation have had it with sex and drugs and doing it in the road. They are looking for something deeper.

If there’s one artist who most embodies this line of thinking, it’s Sufjan Stevens, whom Banhart conspicuously fails to include in his freak-folk canon. (The omission may be accidental, but even Iron & Wine made it onto Banhart’s “Golden Apples” compilation, despite the fact that he and Sam Beam had never met.) Stevens is probably Banhart’s only real competition as quiet music’s leading light. Yet his very earnest Christian faith sets him apart from the others, just as surely as Hegarty’s sexuality does. And just as Hegarty’s music engages his most private sexual thoughts, Stevens’ thoroughly indulges his spiritual preoccupations. His music publishing company is called New Jerusalem Music. His album “Seven Swans” includes songs titled “The Transfiguration” and “Abraham.” And on tours for that album, he and his backing band wore white clothing with tiny, feathery winglets mounted to each shoulder blade.

Although Stevens proclaims his Christian faith—or what he calls “eternal things, supernatural things, things of mystery”—he is careful not to proselytize. His music and message appeal to audiences that would ordinarily shrink from such imagery. One example: I was recently introduced to an employee in Warner Bros. Records’ artists and repertoire department (the folks who sign the bands). She specializes in alternative rock, and she spoke excitedly of Stevens’ unexpected success. “It’s about the fact that the Internet gives kids in Omaha access to the best record stores in New York,” she said. “It’s about the fact that everything is Coke and Pepsi these days, and it’s all mass-marketed to kids, and they just want some relief.” Yet when she handed me her business card, she made a theatrical gesture of crossing out the logo for Word Records, Warner Bros.’ Christian music imprint.

Of course, Stevens has not made religion his only subject. His breakthrough release, 2003’s “Michigan,” was a concept album about his home state, and the first installment in his audacious 50 States Project. Intending it as a lifelong undertaking, he has promised one release covering every state in the union. (“Casimir Pulaski Day” appears on “Illinois,” which was released in July.) Where the current wave of politicized belief assumes that we are one nation together in Christ, in Stevens’ songs creed is just one aspect of a person’s life. As the working-class narrator of “The Upper Peninsula” sings: “I live in America with a pair of Payless shoes … / I’ve seen my wife at the K-mart / In strange ideas, we live apart.”

Stevens’ faith stands in sharp contrast to the born-again rhetoric that has become synonymous with Christianity in this country. For him, faith is not something into which you are “born again” after a series of mistakes, it’s something with you from the first day of your life.

“It sounds like Devendra kind of grew up in this strange kind of cultish environment,” he says, “and I don’t mean that word in a demeaning way. I think we probably come from similar backgrounds. There’s a little bit of that in my history.” As he explains it, the name Sufjan (pronounced SUF-yan) is an Armenian term that means “comes with a sword.” He acquired his name much like Banhart did—his parents were involved in a spiritual movement called Subud. Started in Indonesia by a man named Muhammad Subuh Sumohadiwidjojo, its main practice is the latihan kejiwaan, a spiritual exercise during which members claim to purify themselves and communicate with god. While Stevens balks at discussing the topic in depth, it’s clear that he has seen the extremes of ’60s indulgence, and understands the power and misuse of faith in a way that few ever will.

“The religious environment I grew up in was so varied, so inconsistent, and had so many faces,” he says, explaining his turn to Christianity. “What I perceived in major organized religion was order and a kind of consistency I didn’t see in my family life.”

His faith is still prone to subtle doubts. In “Casimir Pulaski Day,” after the girl succumbs to her cancer, the narrator contemplates “All the glory that the Lord has made / And the complications when I see His face,” and his conclusion is almost rueful: “And He takes and He takes and He takes.”

“People see the term Christian attached to me and they think, ‘OK, he must be fundamentalist Christian, and then he must be a Republican. Oh, then he must have voted for George Bush, so he must be a bigot.’ It’s just like one thing leads to another,” he says. “I’m sure if I were to sit down with Jerry Falwell or anyone like that it would be very uncomfortable. Yet in theological terms, we worship the same God, and that’s a very awkward kind of thing to reconcile with. The religious environment is a big problem, but I don’t really know how to start talking about it.”

At this, Stevens looks pained, as he has periodically during the interview. But rather than divert the conversation, he turns it into a humorous riff, the kind of comment so rare among demagogues. “Ohhh,” he says almost giddily, “the clarity of all things will be revealed in the afterlife, and there will be a refinement of character for all of us, I hope. It’s all politics anyway—religion here is politics.”

***

STEVENS’ final thoughts come back to haunt me when I visit Sam Beam, a.k.a. Iron & Wine, in his hometown of Miami. Not only is Florida a red state through and through, it’s ground zero for the glitziest American political spectacles of the 21st century—site of the 2000 presidential debacle; site of the flight school where Mohamed Atta and several other Sept. 11 suicide bombers were trained; site of the soap opera that surrounded Terri Schiavo’s deathbed struggle. On the afternoon of my visit, Schiavo passes away in Pinellas Park, on the state’s west coast; that evening Beam and I eat dinner at Versailles, a Cuban restaurant in Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood, a half-dozen blocks from the former home of refugee Elian Gonzalez. It is the night before April Fool’s Day.

Beam, a native of Columbia, S.C., moved to Florida to attend film school in Tallahassee. He stuck around when he got a teaching gig at Miami International University of Art & Design, a job he took so he could spend more predictable hours with his kids. With his prominent forehead, lantern jaw and woolly three-inch beard, he resembles central casting’s idea of a Southerner—a fringy NASCAR dad, or a cleaned-up character from “Deliverance.” Hanging out with him, though, is like chatting with a frumpy young father. Miami doesn’t have a thriving indie rock scene—its polyglot ethnic mix of black and Latino immigrants is inhospitable to the lily white world of underground pop—but Beam doesn’t mind. At one point he explains how life on the road is different for a 30-year-old dad than for a 25-year-old aspiring rock star: “I guess it’s pretty sad, but when I’m out on tour, a lot of people are like, ‘C’mon, let’s go get [messed] up,’ and I’m like, ‘Dude, I’m tired. Tour is the one chance I get to get some sleep.’ “

As the hour grows late, we stop by a British pub called Churchill’s, the closest thing Miami has to a rock ’n’ roll dive bar. There Beam tries out his truly Jeff Foxworthy-grade material. His wife just gave birth to their third child, and his in-laws are in town, so I ask how he got time away. “It wasn’t that hard,” he answers. “All I did was say, ‘Hey honey, I gotta go out and hang out in a bar with this interviewer tonight. What can I say, I’m doing it for work!’ “

Beam is a kindly sort, and his accent makes these words bleary and soft. He may be the sweetest, most soft-spoken and self-effacing interviewee I’ve met outside of the late singer-songwriter Elliott Smith, a man who refused to do more than shrug at his own talents. But unlike Smith, Beam doesn’t have a trace of that Hamlet thing. “I try to keep a level head about the importance of what I do,” he says. “It’s not like you’re fighting fire, or feeding someone, you’re just writing songs. When I first started I was already accustomed to being in front of people through teaching. The weirdest thing was when they started singing along.”

The only talk that seems to draw Beam out is a discussion of those songs, the ones his audiences regularly sing along to, songs such as “Naked As We Came” from his second album, “Our Endless Numbered Days.” The album has won him a strong following among fans of laid-back, easy-feeling artists such as Ben Harper and Jack Johnson. To understand what a feat that is, you need only listen to Beam’s lyrics, which linger on life’s hardest facts:

One of us will die

inside these arms

Eyes wide open

Naked as we came

One will spread our

Ashes ‘round the yard

She says if I leave

before you darling

Don’t you waste me in the ground

It’s the kind of song that spreads like a hush inside your heart. And suddenly I realize why Beam doesn’t like talking very much. Anything he’d have to say is right there—life and death and love, and the tiny role religion and politics actually play in them.

“There is a lot of religious imagery and stuff in my songs,” Beam says. “It’s something I’m interested in based on my background, and the people I know, and the whole country’s history. But growing up in the Bible Belt actually pushed me away from religion, instead of creating it in me. That’s all there was, so when you got out you wondered, ‘Was I tricked the whole time?’ You realize the world isn’t that black and white. It made me extremely skeptical, even if I still hold a lot of those stories from my upbringing very dear, and even if I think it was great as far as teaching you the Tao.”

Lest you wonder if Beam has his own religious peculiarities, he explains further: “I don’t mean Taoism, but these tenets that sort of run common through all religion, the basic moral values.”

Unlike the current presidential administration, Beam, Stevens, Banhart and their cohorts are not the types to proselytize. They have no particular technique for living. Yet by their quiet example they show why this music is spreading. More than any of the others, though, Beam is the face of the Soft Revolution. He’s the guy who wants to believe, who wants to be good, who wants nothing more than to have a wife and family, a good job and an off-the-radar life somewhere nice like Miami, where you can take your kids to the beach a couple of times a week.

These quiet people are today’s equivalent of the silent majority. All they want is for the world to please calm down, please. So, those of you who are faithful and stable and undemonstrative, take strength. Those of you who hold as your foundation a quiet kind of belief—in family life, in spirituality, in the Tao—the Soft Revolution speaks for thee. And it will grow louder.

Devendra Banhart’s “Cripple Crow” will be released Sept. 13. Antony and the Johnsons play L.A.’s Vista Theater Sept. 22 and the San Diego Women’s Club Sept. 23. Iron & Wine will release “In the Reins,” a collaboration with Calexico, on Sept. 20.

***

WHO’S MAKING NOISE IN THE SOFT REVOLUTION

Antony and the Johnsons: “I Am a Bird Now” (Secretly Canadian, 2005)

Antony Hegarty is an endomorphic cross-dresser from Manhattan who sounds like Nina Simone, looks like the Pillsbury Doughboy and uses his severe countertenor vibrato to sing almost exclusively about trans-sexuals and transgenderism. Not surprisingly, he has spent the past half-decade playing mostly to fans of experimental theater and at gay, after-hours cabarets. His latest album, however, has attracted a new audience of heterosexual indie rockers. What happened? He embraced the soulful, driving rhythms of ’60s R&B and recruited a number of high-profile guest stars—Rufus Wainwright, Boy George and mentor Lou Reed—to contribute to his album.

Devendra Banhart: “Rejoicing in the Hands” (Young God, 2004)

The 24-year-old Banhart is another warbling male singer, though his voice alternates between the profound goofiness of Cat Stevens and the scratchy moodiness of Billie Holiday. While his early recordings were whacked-out, surreal and quite inaccessible—like artifacts from some yet undiscovered animist religion—his new music is dub-inflected and more traditional. A naturally charismatic leader with movie-star good looks, he will release his new album, “Cripple Crow,” in September. It is reportedly an effort to transform him into freak-folk’s Bob Marley, an ambassador to a wider (albeit whiter) world.

Bright Eyes: “I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning” (Saddle Creek, 2005)

This revolving-door solo project by Omaha’s so-called boy wonder Conor Oberst is a bit too grounded in plain old folk tradition to fit comfortably within the freak-folk rubric, but he’s clearly an important figure in modern pop. He’s long been called the Bob Dylan of Generation Y, not only for his self-consciously poetic lyrics but for his clear political engagement and his intense cult following. (Bright Eyes has sold twice as many albums as any of these other artists.) While not actually a boy anymore—at 25, he’s older than Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom—his easily accessible songs and star power mean his career will probably last long after any “quiet music” phenomenon has passed.

Iron & Wine: “Our Endless Numbered Days” (Sub Pop, 2004)

This “group” is also a solo project, fronted by 30-year-old Sam Beam, a bearded Southerner whose face wouldn’t be out of place in a Civil War-era daguerreotype. His music, though, would fit right in with the Laurel Canyon folk-rock movement of the 1970s, which brought us Crosby, Stills & Nash, James Taylor and Jackson Browne. Any moodiness is leavened with hope, and his songs are lilting, simple, breezing along at an easy-feeling, mid-tempo pace.

Joanna Newsom: “The Milk-Eyed Mender” (Drag City, 2004)

An elfin 23-year-old harp prodigy hailing from Nevada City, a hippieish community north of San Francisco, Newsom combines the rhythms of Mali and the Celts, the literary complexity of Bob Dylan and a love-it-or-leave-it voice that sounds like a preteen girl’s with a slight lisp. Her music is an acquired taste, but for those who fall for her, she’ll seem like the most conspicuously gifted member of this class—for her instrumental prowess, the discipline of her songwriting and the funny/sad content of her lyrics.

Sufjan Stevens: “Illinois” (Asthmatic Kitty, 2005)

Stevens’ latest album, “Illinois,” marks the second installment in his 50 States Project, an effort to write an album for every state in the union. Stevens shows every sign of being prolific and diligent enough to fulfill what is, on its face, a ludicrous undertaking. He’s released five albums since 2000; they regularly clock in at more than an hour in length; and the two 50 State albums released thus far are as well-researched as the Depression-era guides produced by the Works Progress Administration. While it’s a gimmick that grabs your attention, his execution is what keeps you listening. Stevens is a deeply faithful Christian, but his songs portray characters filled with both uncertainty and devotion. Could this project be an effort to understand our nation’s much-talked-about religious mania? Hard to tell: To date he’s only sung about blue states.

Alec Hanley Bemis writes the “Psychic Hipster’s Pop 10” column for the L.A. Weekly, and after finishing this story he took a job with Faith Popcorn’s BrainReserve. He also co-owns a record label, Brassland, which documents a community of musicians centered in Brooklyn and New York City.

Originally published in the Los Angeles Times on August 28, 2005.