WE WANT THINGS TO FIT, LIKE SQUARE PEGS IN square holes. But there are no square holes. There are stones in shoes, bumps in roads, clouds in skies. It rains and pours, and each drop triggers a drum, a fretless bass, a guitar hero, a fiddle, a tuba, a brass band, otherworldly organs, three singers so earnest they sound as if they’re pleading for their lives. It’s like a Disneyland treatment of Deliverance — three hicks singing “It’s a small world after all” in such a way that you can’t tell when one member of the trio lets off and the next one starts.

In The Band’s music, it is a small world: You hear bar-band rock & roll steeped in crotchety American folksongs, but you also hear authentic soul — voices joining, musicians who just plain care. It’s the best beer-commercial music of all time.

Last year, Capitol reissued The Band’s eight albums for the label. The Last Waltz, a 1978 album and film documenting their star-studded farewell concert, has just been re-released. When The Band’s debut, Music From Big Pink, emerged late in 1968, it was already clear they had invented something unique. It was a vibe record in the guise of rock music — a warm-sounding pastiche in which “feel” and songwriting were taken equally into account. At the same time, they are one of the most potent precursors of Americana, a broadly defined catch-all genre coming into prominence today. Only now does The Band’s music make sense, so let’s explore their sound.

Too excited to keep time, Levon Helm, the drummer-vocalist, injects speed into the group, but he also plays mandolin, bass, guitar . . . (The Band mix things up a lot.) His Arkansas accent comes out as yelps, growls, a gravelly thing. He sounds like the last Civil War soldier, one who has wandered too far north. There he entertains with old tales like this one: “In the winter of ‘65/We were hungry, just barely alive/By May the 10th Richmond had fell/It’s a time I remember oh so well/The night they drove old Dixie down and the bells were ringing/The night they drove old Dixie down and the people were singing/They went la la-la-la-la la-laaah-la-laaah . . .”

Two more singers join in. Bassist Rick Danko’s high whine is mellow, quiet, kind of blank. His efforts ground the group in midtempo rock, but you’ll be glad someone’s holding this ship together as the rest of the group skirts more dangerous seas. Such as Richard Manuel’s voice. A sad man with dark eyes and a hollow face, he has a soulful sound he rides deep: “I’m a thief and I dig it!” “Oh, you don’t know the shape I’m in.” “The storm has passed/There is peace at last/I’ll spend my whole life sleeping.” Occasionally he has his way with the drums in an awkward, clip-cloppity Clydesdale style. (Where Helm always got ahead of himself, Manuel was always trying to catch up. They provide The Band’s loose yet locked-in rhythms and subrhythms — rhythms that break up space in untoward ways.) On the early records, Manuel contributed many songs — longing ballads composed on piano — but by the third album, Stage Fright, he’d stopped writing, and you can’t help but think it’s because, goddammit, that song was never good enough, this life is never good enough. (He hanged himself in a hotel room on a reunion tour in ‘86.)

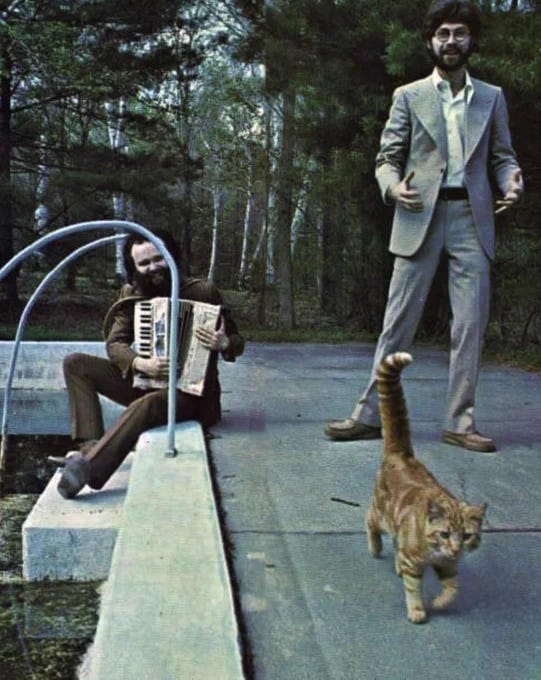

Garth Hudson looks as if he walked off a mountaintop or slunk out from under a bridge. His bearded head is big and round like a lawn dwarf’s or an M.I. Hummel figurine’s. Classically trained, and a bit older than his bandmates, he takes turns playing accordion, Clavinet, slide trumpet and sax. He is also a keyboard explorer who masters texture and leaves the songs…

…to Robbie Robertson, both the star and the silent one. Eventually he went Hollywood with his publishing money and cinema dreams. (In the ’80s he concentrated on soundtracks; to quote a press release, he currently works at DreamWorks as a “creative plenipotentiary.”) Robertson was constantly discovering another piece of his multifaceted heritage so he could write songs about it. “Smoke Signals” deals with his Native American blood. “Rag & Bone” was inspired by his Jewish relatives from the Old Country, such as his grandfather. To quote Robbie: “He was an intellectual, but he made his living in Toronto as a rag man.” Robertson could have been describing himself.

An inimitable and prolific songwriter, Robertson was also a high school dropout who often distanced himself from music, perhaps bothered by the lack of credit musicians are given for their minds. In interviews Robertson comes off as a guy uncomfortable with his own unique genius, reminiscent of the kind of grown men who’ve learned all they know from throwing the I Ching, watching arty movies and reading Aldous Huxley books. He speaks glowingly of the religio-psychedelic writings of Carlos Castaneda and filmmakers such as François Truffaut, Akira Kurosawa and Luis Buñuel. Martin Scorsese, the young director in charge of The Last Waltz, became a close friend.

To an extent, such studies damaged Robertson’s considerable inborn talent. While his later songs dwelt concretely upon legends, forced migration and mystic history — “Daniel and the Sacred Harp,” “Acadian Driftwood,” “The Saga of Pepote Rouge” — he was best when his cloudy myths were viewed through cloudy eyes and effortlessly tapped the magic illogic of rock. What are “Rag Mama Rag” and “The Weight” about, anyway? In “When You Awake,” a kid sits on his grandfather’s knee and Papa explains: “When you awake you will remember ev’rything/You will be hangin’ on a string from your . . ./When you believe, you will relieve the only soul/That you were born with to grow old and never know.”

THE BAND WERE A BUNCH OF CANADIAN HAYSEEDS (save for Helm, a Southern hayseed). They drifted together in Toronto under the aegis of an obscure rockabilly performer, Ronnie Hawkins. Joining one by one, they were all in his band, the Hawks, as of 1961, but they left him in 1964. (Other names they recorded under or considered include the Canadian Squires, the Honkies and the Crackers.) Used to playing fraternity parties and dark, bloody bars, they were plucked from obscurity in the fall of 1965 when Bob Dylan chose them to back him on his electric folk-rock world tour. (Again, save for Helm: Sick of the booing that greeted his first few dates with Dylan, he quit and moved back to Arkansas for the span of the tour.) Documented on innumerable bootlegs and 1998’s Live 1966, the Hawks were electric Dylan’s wild mercury sound.

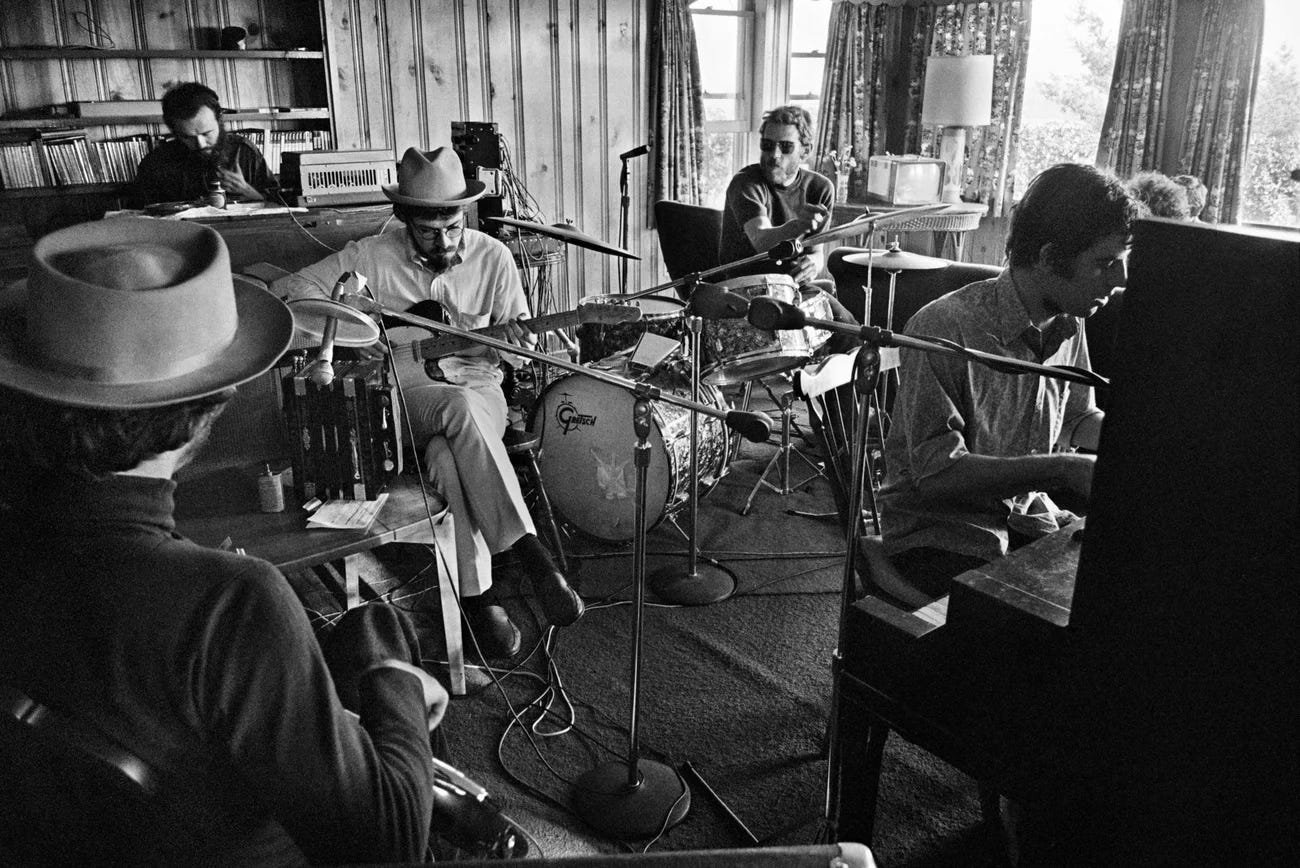

The tour’s final show was in May 1966; Dylan’s legendary motorcycle accident happened in July. To recover, he retreated to Woodstock, and The Band joined him. There they recorded collaborative demos (which later emerged as The Basement Tapes) off and on throughout 1967 at Big Pink, the group’s gathering place. After helping Dylan define rock on tour, they now explored folk music’s outer edges, drawing out new shapes and sounds, weaving in strands of ’50s and ’60s R&B.

When their debut came out in 1968, they faced a barren field. If only by virtue of others’ exhaustion, the group had beaten out the competition. The Beatles had retired from live performance in August 1966; mired in fame, the Rolling Stones were in the midst of a two-year concert hiatus; Dylan would perform in public only five times over the following six and a half years, three of those backed by or accompanying The Band.

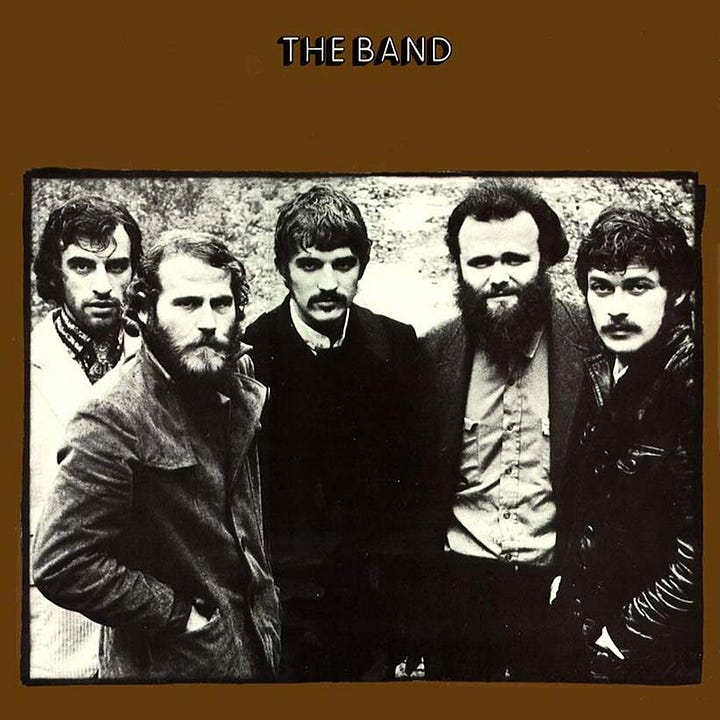

No other musicians had a better claim to being The Band, the word, an archetypal form. In The Last Waltz, Manuel recalls how they came upon it: “It was right in the middle of that whole psychedelic era. Chocolate Subway and Marshmallow Overcoat. Those kind of names, you know?” The world was still fascinated by psychedelic musings and free love; The Band posed in old-timey clothes more 19th century than 1960, and their first album featured a center-spread photograph with the group surrounded by four generations of family and the headline “Next of Kin.”

The Band were the last great rock band before the music began to eat itself and mock its own conventions, before the Ramones and Led Zeppelin, before the genre needed prefixes such as “punk” or “classic.” Dylan had combined folk and rock to create an electrified amalgam — savage and hot. The Band cooled off that molten sound and conceived of a new music combining all that we had heard before. Dylan turned poetry into pop music; The Band found the poetry inherent in pop music’s sound. On their albums you hear pure rock spouting out in a howl as loud and clear as that which Robert Johnson gave to the blues.

EXPLAINING MY AFFECTION FOR THE Band is like describing the rain or answering the dumbest of questions: What is love like? Is the heart a vessel or a bell? Is it a thing that starts out empty and needs to be filled, or a sympathetic tone you hit by chance? Insofar as that’s concerned, The Band are of two minds.

The vessel: When pressed, I might tell you the only Band record worth having is the self-titled sophomore album (usually known as the Brown One, after the cover’s color). It’s rollicking, warbling, snarling and smooth, like listening to all the best singles of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s at the same time while you barrel up and down the slopes of a rickety roller coaster. And here it is, from “Up on Cripple Creek,” The Band’s sole Top 30 single: “Up on Cripple Creek, she sends me/If I spring a leak, she mends me/I don’t have to speak, she defends me/A drunkard’s dream, if I ever did see one.” Love is a vessel. Keep me filled or set me loose.

A bell: After the Brown One came The Band’s quick descent into Malibu, heroin, solo turns at the mike, and pablum — five increasingly disappointing full-lengths on Capitol and three double live albums. (The latter two are middling — Before the Flood with Dylan; the indulgent Last Waltz — but the first one, Rock of Ages, is great.) Yet if this is the sound of your heart, you never want that ringing to stop, and it won’t if you pay heed to the proper frequencies. The fifth song on Northern Cross — Southern Lights tells me this. First there’s an insistent bass line and a couple of clinking synth fills; next there’s a call from the guitar, a response from some horns. Up comes the chorus, and all three voices pull together as they hadn’t since the Brown One: “Ring your bell/Change your number/Run like hell/You can’t hide from thunder/Oh no.”

Hold off the rain. Love is a bell.

Originally published in LA Weekly on April 17, 2002.

Also a big thanks for reposting.

Canadians have an affilinity for The Band. Ronnie Hawkins ( like Helm, American ) passed away in 2022. This article sheds light on his influence.

Saw a video today for the Deep South Band ( oddly, on a flatbed truck in Toronto). Song was even stranger - about cousins. Anyhow, once in a while southern musicians come to Toronto . Good things happen.

Ah, this is so good. Never knew you for a fan. thanks for reposting.