music for heart & breath & floating & falling & dreaming

ALSO: an interview with Richard Reed Parry from Arcade Fire, Bell Orchestre, et. al.

# of Tracks: around 70

Length: 5 hours

Themes: music that works as “lean back” listening ~ ambient dub & some chill classical composition & some haunting folk ~ multiple recordings by Brian Eno, Alabaster DePlume, Julee Cruise, Haruomi Hosono, a band and person named Caroline, Leif Vollebekk, Sam Gendel, and RRP himself ~ a notable thread of musicians from Canada

Link: Spotify — Apple Music — YouTube

Venues like the Super Bowl halftime show or TV singing contests like American Idol or headline slots at festivals tend to feature examples of Extreme Popular Music™—art meant to impress you, to wow you, to maximize zazzle and show off those those jazz hands. This playlist is the opposite of that, a container devoted to music that sits happily in the background — “wallpaper music” as Erik Satie put it (with both humor and affection). The music I’m featuring here could be construed as “ambient” (for lack of a better term); it might evade active perception and slip just under the radar of consciousness.

My selections were built around an excellent new album by Richard Reed Parry and Susie Ibarra. Ibarra is best known (to me) as a participant in the downtown NYC jazz/classical scene revolving around the munificent benefactor John Zorn. Parry is best known as a member of Arcade Fire which, at this moment, let’s be honest, feels awkward. He was kind enough to talk to me about his new record and our tightly focused and deeply engaged conversation appears below.

Note: I’m going to breeze past Parry’s proximity to current scandal1 for a few good reasons. First, I actually approached him and he agreed to do this chat a few days before the news broke of his bandmate’s…erm…situation; he was gracious enough to follow through after that (ongoing) disruption. Second, to misquote The Big Lebowski, “This music abides”; one of the many things I like about ambient music is how it resists cultural relevance.2 Finally, I’ve known Richy for well over a decade—and while we’re by no means intimates, I consider him a friend and fellow traveller. It feels respectful to map this conversation to the roads we share in common.

Other websites on the Internet exist to generate controversy, clicks, engagement, and enragement. This mixtape delivery service shall remain devoted exclusively to music itself.

Spotify version

Apple Music version

YouTube version

The playlist includes songs such as…

^ Joan Shelley: “Amberlit Morning” (feat. Bill Callahan)

^ cktrl: “yield”

^ Emma Ruth Rundle: “You Don’t Have To Cry”

^ Jon Hopkins: “Sit Around The Fire” (feat. Ram Dass & East Forest)

A Conversation with Richard Reed Parry: about his Music for Heart & Breath, and ambient music generally

# of Questions: less than 10

Length: about 2,500 words

Themes: first encounters with the form ~ constructing ambient music in the studio vs. playing it with living musicians ~ a few of his favorite things

I’m pretty sure I first met Richard Reed Parry after a gig at the long gone and much lamented downtown NYC venue Tonic on an autumn night in 2005. He was playing in his indie chamber orchestra project Bell Orchestre; I was there as a record label dude affiliated with the co-headliner Clogs, a different indie chamber orchestra. (Two indie chamber orchestras on a single bill seemed normal; chronologically we were near the apex of post-rock’s popularity.) Both groups had line-ups that intermingled with far more popular rock bands—Richy with (future Grammy-winning™) indie rock group Arcade Fire, Clogs with (future Grammy-winning™) indie rock group The National.

It was clear Richy was the kind of artist whose light inspires heliotropic motion in my creative spirit. He is not averse to seeking popular acclaim or building the platform fame provides, but he is primarily interested in leveraging that acclaim to support more obscure forms of musical expression—be it tribute concerts for cult folk records or instrumental explorations of wave movement. Over the years, it’s been wonderful to watch this guy—easy to dismiss as “the excited-on-stage fella who reminds you of the actor from Napoleon Dynamite”—get to express all sides of his creativity and deepen that expression, in multiple directions. This interview and this moment, catches Richy during a particularly molten run of creative engagements: Bell Orchestre released their first LP in over a decade; he produced the final album from the original line-up of The Sadies3; and he has completed a few new renditions of “Heart & Breath” music, a new form he has invented .

Question: What was your first encounter with ambient music that you might cite as an influence? It should be an experience that’s stuck with you, not just that time some older relative played Brian Eno’s Music for Airports at a family gathering when you were three.

Answer: My first ever memorable encounter with ambient music would be second year of high school at Canterbury Arts in Ottawa, and I walked into our cafeteria and there was this DJ booth made of plywood and covered in graffiti murals that these really cool kids had convinced the school to let them build, so that students could DJ for the cafeteria at lunchtime. (Pretty forward thinking high school I went to.) This was early on at the very beginning of rave culture days in North America, before it was super widespread. Anyway I walked into the cafeteria one day and there was the most remarkable music playing that just made my whole body stop and notice. It had this feeling of expansiveness, like setting foot into some kind of etheric warm bath…echoing harmonicas and dogs barking and then this huge, soft hypnotic bass… I just stood there totally enraptured and listening, then finally asked one of these guys what music it was and it turned out to be “Towers of Dub” by The Orb, from UFOrb. I hadn’t discovered Jamaican dub yet so the whole feel of the music was just so…“other” for me, and so blissful and strange and friendly.

I lacked the confidence at the time to keep hanging around those guys who had brought the music in, they seemed unapproachable and too cool for me, so instead I just found that album at a record store I used to frequent, and for a good while afterwards kept asking the people who worked there “what other music have you got that is like this?” I had good guides in the staff of that record store, Shake Records, and it opened up a whole world to me. Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works, that Moby Ambient record (who woulda guessed). Then that whole musical world seemed to explode outwards in so many directions and I was up for all of it. Mouse on Mars, Oval, the whole Thrill Jockey scene, Bill Laswell…

One thing stands out that differentiates your own profile as a musician from those ambient works you experienced. You're a player and performer at heart, not just a knob twiddler. Most4 of the folks you just mentioned make recordings "in the box." By contrast, your “Heart & Breath” music is inherently dependent on live players. It’s literally based on individual heart beats, and the inhale and exhale of breath.

Yeah — I guess to me ambient music is entirely about the feeling that it imparts, the type of listening it encourages, and some sort of gentle visceral/physical experience that one might have listening to it, ideally? Or at least that’s what pulls me towards various kinds of “ambient music” as a listener. Good ambient music, anyway, hahaha. Ambient is also unfortunately a catch-all term for infinite quantities of infinitely boring music being made.

How did this particular iteration of your Heart & Breath (H&B) music come about? From what I know about you, you’re a woodshedder. Your side projects, solo projects, and passion projects can take awhile to develop — and rarely seem to be a “first thought, best thought” type stuff. Is that accurate? And is that the case with this record? If memory serves, you started working on the H&B concept over a decade ago.

This particular album is in fact, at its core, much more of a first thought best thought kind of affair, rather than a pre-thought, pre-composed type of thing.

There were no written scores this time around, and it is music that was composed by whatever came out in the playing and recording process, and the shaping of the compositions happened sort of half-live and then half after-the-fact in the editing, through studio post-production. Nearly everything on the record is played by myself or Susie, although Sarah Pagé also played some harp on a couple of pieces, and Rebecca Foon played cello on one as well. There was definitely a lot of shaping of the musical forms after the fact in the studio but a lot of them really happened quite quickly in terms of the basic shape or basic elements of a piece. And then we just followed up the raw live recorded material with a lot of detail work afterwards, all while attempting to keep the “live off the floor” feeling alive in the recording.

The last recorded version was a very different sounding 2014 album on Deutsche Grammophon performed on traditional classical instruments. What made this version of H&B come together at this particular time? Is there more to come?

The original Music For Heart & Breath album was much more of a chamber music/classical aesthetic series of pieces (albeit with an experimental bent) where everything was scored and was intended for other ensembles and classically trained musicians to perform it, not necessarily including myself, although I did end up performing on it a lot as well. But it also had yMusic, Kronos Quartet, etc. as standalone ensembles performing those pieces specifically written for them.

In terms of the timing of this one, I had been waiting to do something exactly like this for a while, and then early on in the pandemic Susie and I got introduced and then paired together by the online sample library/DAW website Splice, who commissioned a collaborative album from us, and this is what we made.

There’s another, more classical sounding album’s worth of Heart & Breath pieces that I had already scored and performed some years ago. It never did get recorded, but I’ll probably do that one day soon. And to be honest there’s another, newer Heart & Breath piece that I’m in the middle of writing that is much more of a large ensemble/single piece in the vibe of the latest record, but with multiple drummers, lots of strings and tuned percussion, harp and wind instruments and organ. That is next on my docket. I’m hoping Susie is going to be involved in that one too. She’s such a special new musical comrade to have found, and our collaboration just bore so much beautiful fruit so quickly.

So soon there might be four records of this music. Awesome. But let’s go back a step… What is Heart & Breath music exactly? Is it a philosophy about how timing should work?

It is definitely philosophical in its foundation…

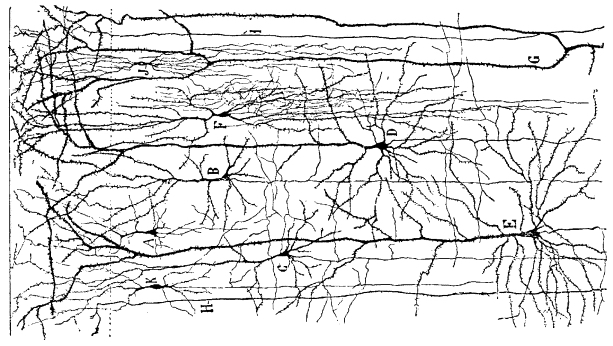

One aspect of it is holding space for the different speed at which every individual operates. Letting those naturally occurring, intrinsic internal dynamics and singularities have an important role in music. Letting these organic, involuntary aspects of the humans playing together be what guides the trajectory of that music. Everyone doesn’t have to jump on the exact same rhythmic bandwagon. There can be different tempos happening simultaneously, sort of orbiting each other rather than being locked in.

The pieces are through-composed enough that it’s not just a free-for-all or an improv session—although there’s infinite room for improvisation. The compositions are constructed in a way that is melodically, harmonically, and gesturally specific, but it’s mostly about setting up a situation where all those musical elements happen in a way that is guided by each person’s own fluctuating tempos rather than a fixed tempo from a conductor, or a central beat-keeper. Having enough good musical material written, and then making room for the body to spontaneously speak…in a way that happens of its own volition. Like…“Ok, my heart is going like THIS right now so that’s exactly what I’m gonna play.”

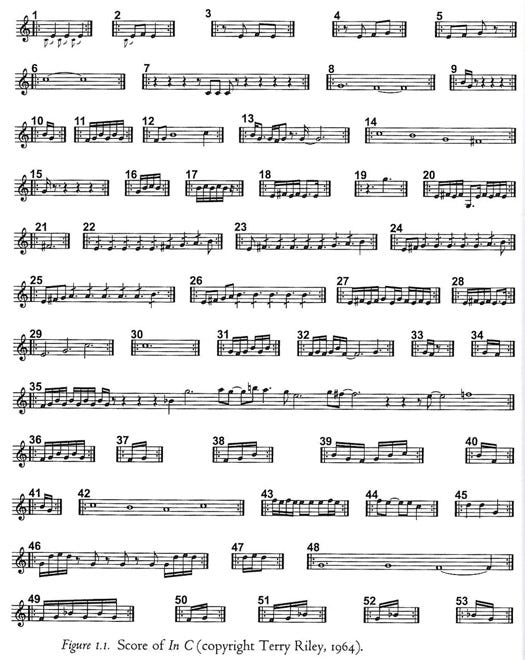

Are there melodic 'cells' or 'modules' that recur between versions of the piece, similar to how Terry Riley's "In C" works? I’m asking this because, while the new recording differs quite dramatically from the earlier album on DG, it is not unrecognizable.

I would say it’s related in many ways to something like “In C,” but there is a different way of framing music here, specifically the rhythmic foundations—letting the actual rhythmic underpinning of the music be determined by more physically uncontrolled factors, rather than our minds…letting the body dictate how things progress, and composing the music specifically so that the performance can be guided by other methods than those we typically find ourselves using by default.

Or rather, using the Heart & Breath way of performing is a new, novel approach that we can add into our musical toolkits, an approach which is slightly more…biological, even more fluctuating than something like “In C.” Perhaps it’s slightly more “sculptural” in a way…?

To my amateur, non-musician ears, I'd say this recording of Heart & Breath seems looser and less linear, structurally speaking. In terms of sonics it seems to fall into a more baritone register, and is more driven by rhythm or polyrhythm than melodic instrumentation. Was that a plan? Or just a function of you and Susie being rhythm section players at heart?5

A lot of these new pieces anyway, I hear them as being sort of related to mobiles: sculptural, but in musical form—groups of motifs that belong together but that are all slowly spinning and rotating and constantly changing their rhythmic and harmonic relationships in beautiful ways. There’s still an overall composition that’s been carefully constructed—groups of notes and melodies and harmonies and rhythmic motifs that all belong together—but we are putting them in motion and then watching the different ways in which they can play off of each other every time a piece is performed. But then I also think this music is much more fluctuating and “alive” seeming than any mobile.

And sonically, yes, for sure, I’d say it’s a lot of baritone register stuff, haha. A lot of wooden and metal percussion sounds. Lots of very specifically tuned drums, and it’s also very upright bass heavy. I used the upright for so many different types of textures, in all the frequency ranges really.

If I were to point to a commonality between the versions of H&B music I've heard, it's that each rendition conveys a shared yet distinct sense of motion and how time passes. If Satie's Gymnopédies are about walking in place, as if on a very leisurely treadmill—and if Eno's Music for Airports is about sitting still while ghostly activity stirs around you, like the experience of a few blurry, sleep-deprived hours in an airport waiting lounge—then this new version of H&B recalls slow motion, organic machinery.

There's an imagined kind of technology that's been theorized called a wetware computer. H&B music reminds me of a large-scale version of how such a device might operate: there are mechanistic parts reorienting, there are gears shifting into place, but the parts of the machine are warm, moist and organic, not cold or metallic. Is that sound just a natural outgrowth of music built around the motion of lungs and hearts?

Yeah, again, I think there’s something in this music that is related to kinetic sculptures or maybe, more accurately, dynamics that occur in nature: Environments or organisms that have a lot of moving parts and some aliveness to them that comes from the fundamental, always-fluctuating nature of all the different moving parts. Hence “rhythm and tone fields” in the title of our new record. Fields as in both human energy fields and also big outdoor spaces—infinitely detailed spaces full of gently complex moving elements, and creatures of all sorts.

It’s my perspective that all great art stands on the shoulders of giants. Can you recommend three pieces of art that inform this body of work? Let’s define the word “art” broadly. It could be a piece of writing, a film, a painting, etc.

Alice Coltrane’s “Galaxy in Turiya” from World Galaxy (Impulse! Records, 1972): I hadn’t actually heard this music when I started writing the Music for Heart & Breath pieces, but when I did discover it I was floored—such simple, elegant writing brought to life in the most sprawling, expressive, pile-on fashion. There’s a direct musical relationship here, I think, in that the universe (no pun intended) of World Galaxy is really just based around these simple drawn out melodies, often played in unison by much of the ensemble, and then all this kind of loose, dazzling pointillistic activity that happens around and in the wake of these big, unified melodic motifs. Like big elegant monochrome ships sailing through a sunlit ocean, with waves going everywhere.

Takeshi Kitano’s “Kikujiro” (Sony Pictures Classics, 1999): One of my favourite movies of all time. This film ambles forward at its own meandering pace in a most lovely way that I’ve never experienced elsewhere. It holds one’s attention so thoroughly and is so delightfully absorbing, yet is held together by the simplest and gentlest of narrative arcs. The story itself is almost beside the point and takes a backseat to the “living in the now”-ness, the moment to moment activity, and mood/pacing. Also, as an aside, the fact that Takeshi Kitano managed to star in this and direct it at the same time is just mind-blowing to me.

James Turrell’s “Into The Light” retrospective (on view at MASS MoCA through May 1, 2025): Turrell’s art is really paradigm shifting stuff, in a way that I find so deeply satisfying. You can think about it or not whilst seeing it. It can be a purely physical/sensory experience or you can go down so many wondrous perceptual thought avenues, trying to figure out what’s happening, what you’re seeing, whether you’re seeing what you’re seeing or not. Chasing your own perceptions and noticing your own responses to your own observations brings a person into such a cool, meditative, confused, mindful, no-mind, thoughtful, visceral, experiential place.

Extra Points:

• isomonstrosity, a pandemic symphony in rap and avant-pop: My label Brassland just started to unveil what I suspect may be the most successful-from-the-jump project in the label’s history. Inspired by the mood and the constraints of the Covid-19 quarantines of 2020-21, three collaborators6—Ellen Reid, Johan Lenox, and Yuga Cohler—solicited scores from about a half-dozen contemporary classical composers, then recorded those contributions with International Contemporary Ensemble, with all the contributing musicians working in isolation. Later they layered on vocal contributions from a deeply eclectic line-up of singers and rappers.

The FADER has already called it “quite possibly the platonic ideal of a pandemic album” (while acknowledging the “pandemic album” is getting old hat). Brooklyn Vegan said it was "a very cool dose of out-there, psychedelic rap music.” It’s getting spins on SiriusXM radio and has made it onto a half-dozen significant Spotify playlists, including support by their POLLEN brand devoted to music that is “Genre-less. Quality first always.” Anyway, I’m very proud to help shepherd this release into public view. Hear it on your preferred platform at this link: brassland.ffm.to/isomonstrosity

• Questlove’s tribute to Greg Tate: The cultural critic, musician and NYC icon died in December 2021. His friend and admirer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson posted this playlist in tribute. It pairs well with my new ambient playlist, and is “further listening” if you get intrigued by the Pharoah Sanders playlist I’ve shared below. Where this month’s primary playlist is about yogic vibes and folk forms and slightly detached voices, Quest’s is about jazz and R&B and muzzier sounds and their fusion into what’s sometimes referred to as soul jazz. It’s more Black and has the feeling of burning embers of an ancient fire. Unrelated: my “lost” interview with Questlove can be found elsewhere on this Substack.

• Dirt: Daily newsletter about entertainment: The self-penned description of this newsletter is kinda bullshit. Dirt is more like cultural commentary with bite. If you’re sardonic and/or old, you might remember Spy in the 1980s, The Baffler in the 1990s, and Suck.com on the cusp of the 2000s. Dirt is kind of like that, only for now times. I don’t read it religiously — but when I do, I find myself tickled and provoked.

People Who Died: Pharoah Sanders — Julee Cruise — Anton Fier — Jamie Branch

I’ll be honest, I’m just starting to dive deep into the music of Pharoah Sanders. Of course I’m familiar with it, and him, but not in great detail. So indulge me as we explore his discography together:

Or if you’re short on time try this expansive yet economical mix by Detroit musician Warren Defever instead: “70 minutes, 22 tracks, 1966 - 2005. Pharoah's average track is 13 minutes long, many are 25 minutes long, i did a couple edits.” I’ve also leaned into saxophonists in the primary mix this month: cktrl, Alabaster DePlume, Sam Gendel. None of them will inherit Pharoah’s throne, but all of them and all of us now live proudly in the shadow he casts.

Musicians die. But their recordings remain. And so the the music lives. And if it needs to be said, remember, we need to live also.

To read about the unresolved complications with his day job, I’d have to point you toward a different web publication with more resources for investigation and far more interest in stirring the pot. (When it comes to pots, I just watch ‘em.)

That’s not to say ambient music is culturally irrelevant or resists cultural markings. By all accounts, from folks I know in the music industry and from my Twitter feed, ambient music is going through a bit of a renaissance rn. A sub-theme of this mix are contributions from Richy’s fellow Canadians. I almost subtitled the mix Canadambient. Thankfully, I didn’t.

The Sadies frontman, Dallas Good, died suddenly at the age of 48. I posted a playlist about it elsewhere on this Substack blog.

Most not all! Laswell and Jamaican dub have roots in live instrumentation even if their renown stems from the abstraction they layered on top of those performances.

No pun intended.

Ellen won the Pulitzer Prize for Music the year after Kendrick; Johan’s contributed to records by Kanye and Travis Scott; Yuga’s a good enough computer engineer he doesn’t have to work full time as a musician. (Bless.) Anyway, an eclectic group!