Steve Albini started fires, 1962–2024

a culture hero who defined my 1990s (mostly) trolled with a heart of gold

I loved Steve Albini. I did not know him1 but he was a primal influence, and changed what so many of my peers thought music could be—as a sound, a scene, a vocation.

The first time I saw him in the flesh was at a short-lived concert venue in Chinatown NYC called Thread Waxing Space.2 It was a gig by his band Shellac. The group were just getting started, but they would continue for the next three decades.3

In the scrum of remembrance in the days after Albini’s fatal heart attack I found this video clip from that night:

I was 19 years old. Shellac hadn’t yet released an LP of their own. But Albini’s best-known job as a recording engineer4—for Nirvana’s In Utero—had been released that past autumn. And then…

A month before the Thread Waxing Space show Kurt Cobain killed himself with a shotgun. The weirdo DIY energy of indie music had mutated into grunge’s commercialized angst. Shellac’s show captured and recapitulated a particular rage against that development.

Is it any wonder this gig changed me?

Thirty years separate that night (May 9, 1994) from Albini’s death (May 7, 2024). It’s taken me back…

I have no intention of whitewashing5 the controversial parts of his life as a punk rock public intellectual. (Yes that’s what he was.) In remembering him, it’s easy to focus on his often illuminating, always coruscating takes on the music business, career ambition run amok, or how to mic a drum kit.

Instead, I’d like to highlight some less viral and more revealing statements—a pair of later-in-life Albini quotes about musical communities. They sum up why he loved organic music scenes—underground cultures!—and why so many of us loved him for his committment to music as a way of life.

From an unpublished interview with poet Damian Rogers:

“I cherish my relationships with the people I’ve met through music. Those people mean the world to me. The respect that I have for them is unconditional, and they are worth my attention and admiration because of what they do and the kind of people they are. It’s not transactional.”

From a conversation Albini had on the Kreative Kontrol podcast:

“You build these people into your lives and then suddenly they’re gone and it’s like holy crap I have to rebuild my world view now because this elemental part is gone”6

Also there was the music itself…

# of Tracks: 40+ tracks

Length: about 3 hours

Themes: John Bonham quality drum sounds on the regular ~ room tone always ~ well documented intensity ~ underappreciated tenderness ~ documentation of the deepest, least cliched female singers ever (Joanna Newsome, Kim Deal, PJ Harvey, Mimi Parker, Nina Nastasia) ~ an ethical center you can hear (with a tangy spice of “edgelord shit”)

Links: Spotify | Apple Music | YouTube

The day after Albini died, I started assembling a playlist of recordings he made with his own bands and with others. I’ve made small tweaks and additions since then. But essentially I knew what songs to include from the jump because large swaths of Albini’s discography are tattooed deep in my guts, my brain, my heart.

I considered ending this post right here, saying I don’t much care what I have to say about Steve Albini. I cared about what he said. I care about the recordings he made. That now that he’s gone, I’m going to miss him.

But losing him demands more. I haven’t lost a culture hero. I’ve lost the proverbial angel and devil on my shoulder, a voice that informed how I made my way around the world…for better and worse. How to be ethical. How to be cranky and blunt and edgy to the point of offensiveness. How to focus on humor and truth so, on balance, you might make the world better not worse.

Find the playlist on… Spotify | Apple Music | YouTube

Want to support AHB’s Goodies? If you enjoy my mixtape delivery service but can’t commit to a subscription, there is now a one-time donation option. Visit Ko-Fi to throw a few dollars in the tip jar.

A person who started fires

Since Albini’s death, I’ve absorbed countless appreciations and articles written about him. To sharpen my understanding of his cardinal influence on independent music. In the most revealing profile7 I discovered that his father helped fight forest fires. (True story. You can find a report Frank A. Albini wrote called “estimating wildfire behavior and effects” here on the website of the US Dept of Agriculture’s Forest Service. It’s a dense, mathematical tract full of graphs, data visualizations, and technical terms and phrases like “nomograph,” “crown scorch height,” and “a fixed value of Byram’s intensity.”)

Learning this kinda gave new meaning to “Kerosene,” perhaps the most iconic recording by Big Black, the first of Albini’s bands to establish his reputation. The song is about sex, arson, and boredom in a small town.8 To call it nihilistic is an understatement. (Was it, on some level, inspired by dark autobiographical fantasies? You betcha. Albini was born in California but raised in the small city of Missoula, Montana—population approx. 70,000 in the 1970s.)

The notion of Albini plus fire brought me back 13 years to the night St. Vincent covered “Kerosene” at NYC’s Bowery Ballroom9 during a tribute concert honoring Our Band Could Be Your Life, a 2001 book which introduced 21st century kids to Albini’s legacy.

Albini was a firestarter. He enflamed people.

He started a fire in me. In so many of us.

I am thankful.

The playlist includes songs such as…

^ Pixies: “Where Is My Mind”

^ The Jesus Lizard: “Boilermaker”

^ Nina Nastasia: “This Is What It Is”

^ Palace Music: “New Partner”

^ The Breeders: “Off You”

Some words about his “role in inspiring ‘edgelord’ shit”

“I think the kind of music Big Black made was a reaction against a move we saw afoot to make punk music prettier and more normal so the squares could like it. We reacted against that by making music that reflected the opposite impulse, the sensation of being outside rather than wanting to be included.” — Steve Albini10

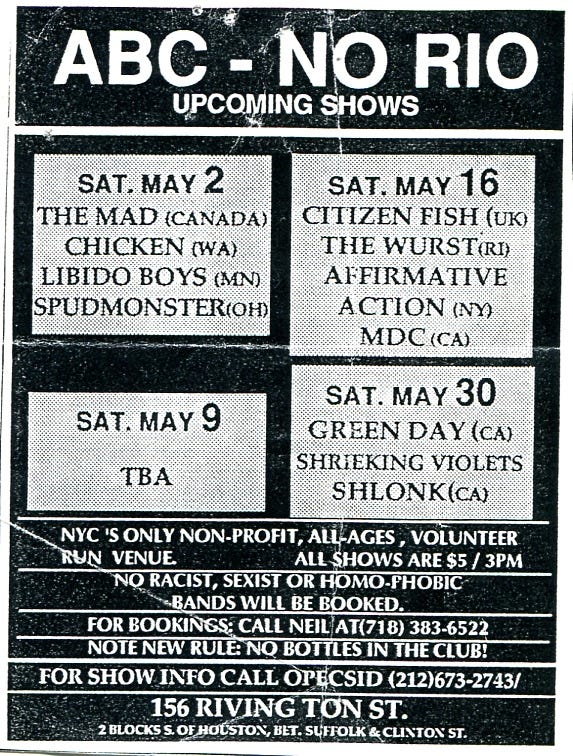

When I think about my connection to Albini’s work and perspective, I remember high school in the suburbs. I mostly didn’t hang out in my high school. I hung out in 7-11 parking lots in neighboring towns; with ska and alt-rock aficionados and riot grrrls; in New Jersey basements and Connecticut VFW halls hosting DIY shows set up by fellow zine makers; with teenage punks who chanted along with Green Day when they played ABC No Rio11 on the Lower East Side. Newly inspired, those young punks would move to NYC and metamorphose into ravers or skaters; or else stay home, get depressed and threaten suicide out loud to their Westchester yuppie parents. (My mother wasn’t really a yuppie. My single-parent family didn’t make enough money to qualify. But I’m pretty sure I also threatened suicide and equally certain I didn’t mean it.)

Which brings me right back to “edgelord” shit in a particular place and time.

The phrase “edgelord” did not exist in the 1990s but I remember the ragamuffin gang of suburban urchins I ran with talking about “causing a ruckus.” I remember lighting little scraps of paper on fire and extinguishing them in my mouth in an effort to impress people. I remember doing all manner of stupid things in an attempt to shock or be noticed in real life. It was a different world, before the Internet’s endless archive, viral content, and doomscrolling. Niche cultural phenomenon existed. But the underground was underdocumented, the subject mostly of fading memories and occasional, unlikely pieces of scandalous mainstream entertainment. (Those friends who made the migration from suburban punk to NYC street kid would pop up again after they “made it big” in the city. A skater could win a cameo role in Harmony Korine’s debut film Kids. A raver might make friends with Michael Alig, the club kid-cum-murderer portrayed by Macaulay Culkin in the film Party Monster.)

This quote from one of Steve Albini’s last interviews12 took me back to those times:

Now, if I had come of age in a later generation, where you could shoot yourself singing on your iPhone and post it on YouTube and be an international star, like if that was the reality I’m sure I would be an awful person by now, if I had come of age later where I didn’t have to make do with scraps and I didn’t have to just put things together on a shoestring. I’m sure that that would have played into my vanity and that I’d be awful. I feel like being formed in that [1980s] scene tempered me as a person and made me rational and comfortable with less, is a way to describe it. And those scenes were all full of such freaks and weirdos, you know? Like having a guy in your band whose profession was that he was a weed dealer wasn’t a big deal. That was normal. Or having friends who were, like, part time prostitutes or whatever. Or having, you know, like people in the underground – like the real underground of society – all around you. That was normalized. And that also kind of tempered me as a person, made me more open minded about what kind of people are legitimate and what kind of people I should take seriously. I feel like all of that to me – that scene and those people formed me as a person. And I’m grateful for it. Because I know that I was susceptible to influence because they influenced me. And if I had fallen in with an uglier or dumber crowd, I would be a dumber and uglier person.

There is a lot going on in that quote—a taste for economy and efficiency that grows out of scarcity; an entire pre-digital world where global exposure was a rarity; a time when few debated the ethics of sex work and drugs on mainstream platform like TikTok or newspaper editorial pages, much less in the state legislatures now considering legalization measures.

The young Albini who used race-baiting, violent, and homophobic language in zines and subterranean vinyl LPs inhabited a world which preceded the Internet and Vice Magazine, memes and social networks. In recent times, he acknowledged his attempts to tweak the squares with “contrarianism, shock, sarcasm or irony” was “miscalculated,” saying it was “clearly awful” and “ultimately contributed to a coarsening society.”

Even his approach to taking responsibility was characteristically Albini. It wasn’t a celebrity’s Notes App apology—an attempt to be popular again. “It’s not about being liked,” he told The Guardian. “It’s me owning up to my role in a shift in culture that directly caused harm to people I’m sympathetic with, and people I want to be a comrade to. The one thing I don’t want to do is say: ‘The culture shifted – excuse my behavior.’ It provides a context for why I was wrong at the time, but I was wrong at the time.”

He asked no mercy from those who held it against him.

Finally, as he grew older, it became clear that the community he remained connected to—those comrades—were artists and makers who cherished life in the niches. He supported and chronicled underground things only a minority of people would enjoy. He devoted his life to creating artifacts many would consider strange or off-putting. He was a connoisseur of purity. He proved left-of-center culture could be at the center of your life if you devoted yourself to it; that the underground could survive if there were more people like Steve Albini out there documenting it.

And he inspired so many of us to do that work, to start our own fires, to keep burning, and to leave sterling evidence of that cultural output behind.

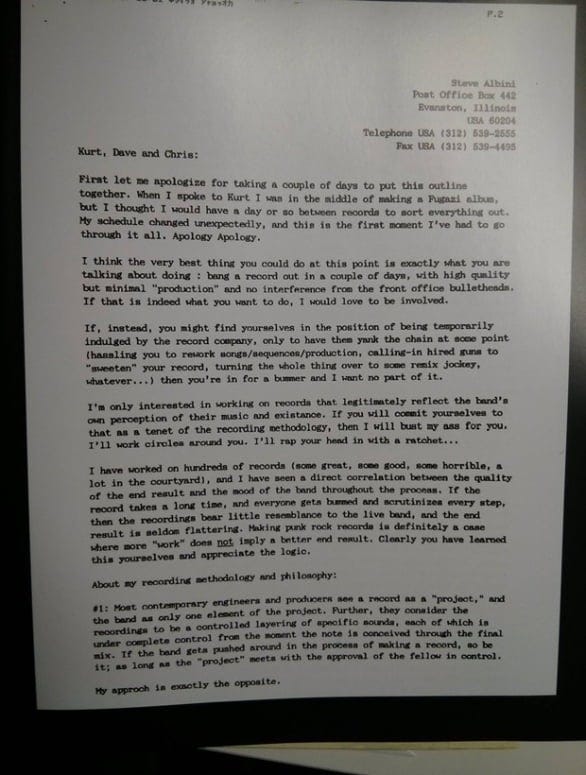

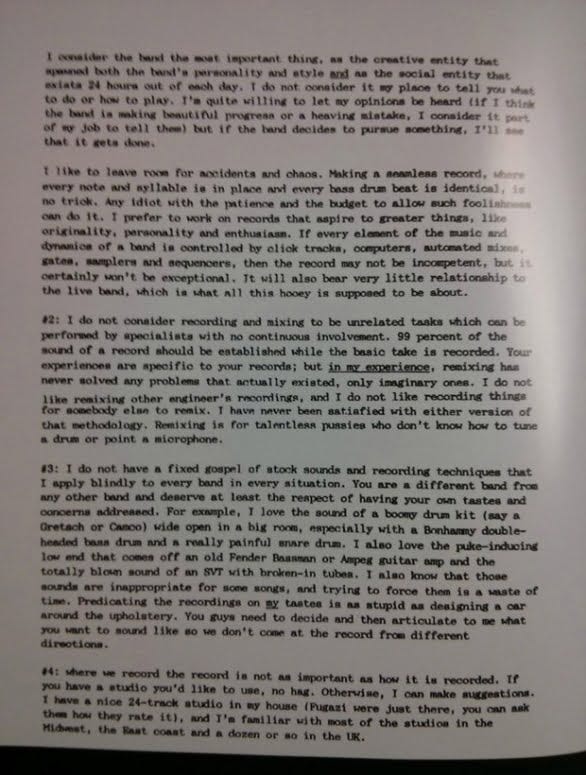

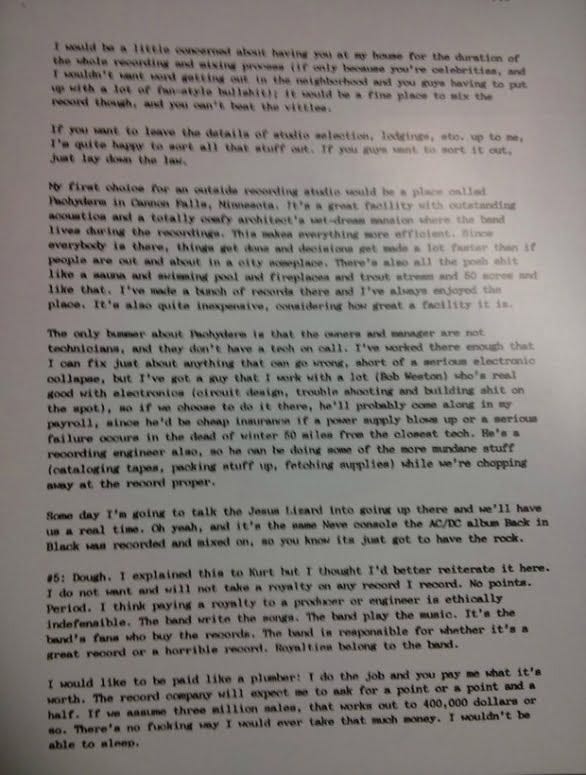

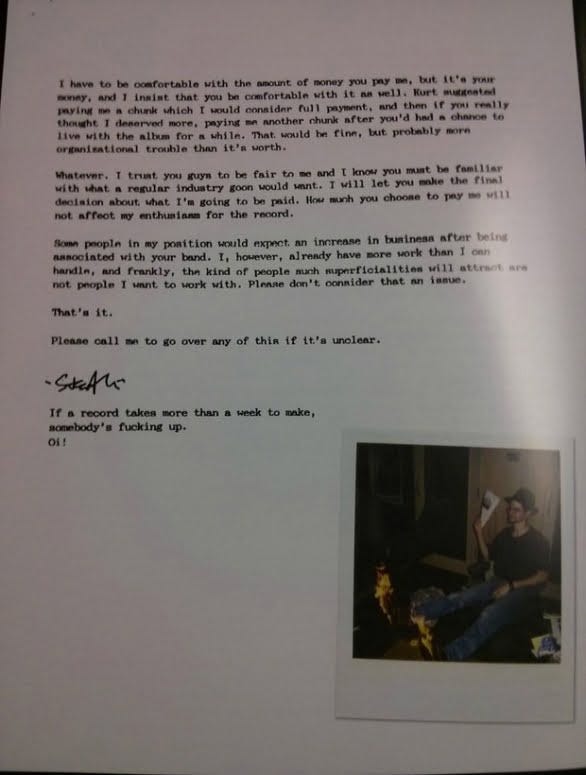

Here’s the conclusion of Steve Albini’s letter to Nirvana which he sent before agreeing to work with them.

That’s a good way to end this.

Requiescat 🎈

Extra Credit: A Few Final Takes On A Post-Albini Universe

• Sasha Frere Jones’ ‘In Memorium’: As I mentioned, I’ve been consuming a lot of Albini since he died — podcasts, profiles in studio nerd magazines I barely understand, and so many tributes. I was struck by Sasha’s reverential yet sober remembrance in 4Columns. I’ll first quote this practical reading list. (I’ve added links.)

Rigor and fairness were important to Albini, a journalism student, guitarist, poker player, and engineer who lives in my head primarily because of his voice as a writer—of kind emails, coruscating letters, unforgivable tour diaries, recipes for his beloved wife, Heather, and tweets, more than you might expect from someone who was sometimes disdainful of digital life. His collected interviews will be of great use, and his 1993 article for the Baffler, “The Problem With Music,” is still the most practical text to offer a musician who has mistaken the idea of signing to a major label with getting a job.

Next these two beautiful sentences of pure projection-slash-empathy:

Albini was as important to me as anyone in music I have come across. His ability and willingness to examine and individuate and map the various nodes of a consciousness indebted to and invested in music was something that made me think that an oversensitive and highly excitable person could maybe be a musician who also wrote.

I’m no musician but a lot of us tried to emulate Albini’s example: Could we ever walk the same trail blazed by this sensitive prickly nerd who reminded us of ourselves?

• David Grubbs’ archival dig on the ‘gram and with Gastr Del Sol: Grubbs was a teenager when he met Albini in the 1980s; by the 1990s he was a frequent visitor to his studios. His Instagram sampler of artifacts from their relationship helped me process Albini’s death in real time—memorializing a session in the same Minnesota facility where he worked with Nirvana; the LP that Shellac pressed up in an edition of 1,000 as a gift for their circle of friends; and a mixtape Steve sent to David when he was a 16 year old zine maker from Louisville, Kentucky.

What a month for revisiting that fruitful pre-millennial Chicago scene! Both Albini and Grubbs helped shape it. If it’s eerie how the last Shellac album was released ten days after Albini’s death, it is equally uncanny that a week later Grubbs’ duo with Jim O’Rourke released a box set.

If you’re a sonic adventurer, I recommend that group Gastr Del Sol’s archival album We Have Dozens of Titles without reservation. They stopped making music together in 1998 but their sound remains hard-to-encapsulate. People have tried. (In its day, it was lumped in with a genre called “post-rock”; last week, the New York Times profiled them.) Your ears will do a better job than language. To prepare those ears, I’d recommend pre-gaming your Gastr Del Sol journey by dipping into this “What We Were Listening To” playlist created to promote the release. It maps the outer limits of recorded sound. What’s incredible about Gastr Del Sol is how they shaped such eclectic, wigged-out influences into their own, quite sensual recordings.

People Who Lived: Marshall Allen, the current leader of the Sun Ra Arkestra, reached his 100th birthday last week. May we all be so lucky to think, at age 50, that our creative life is only at its halfway point.

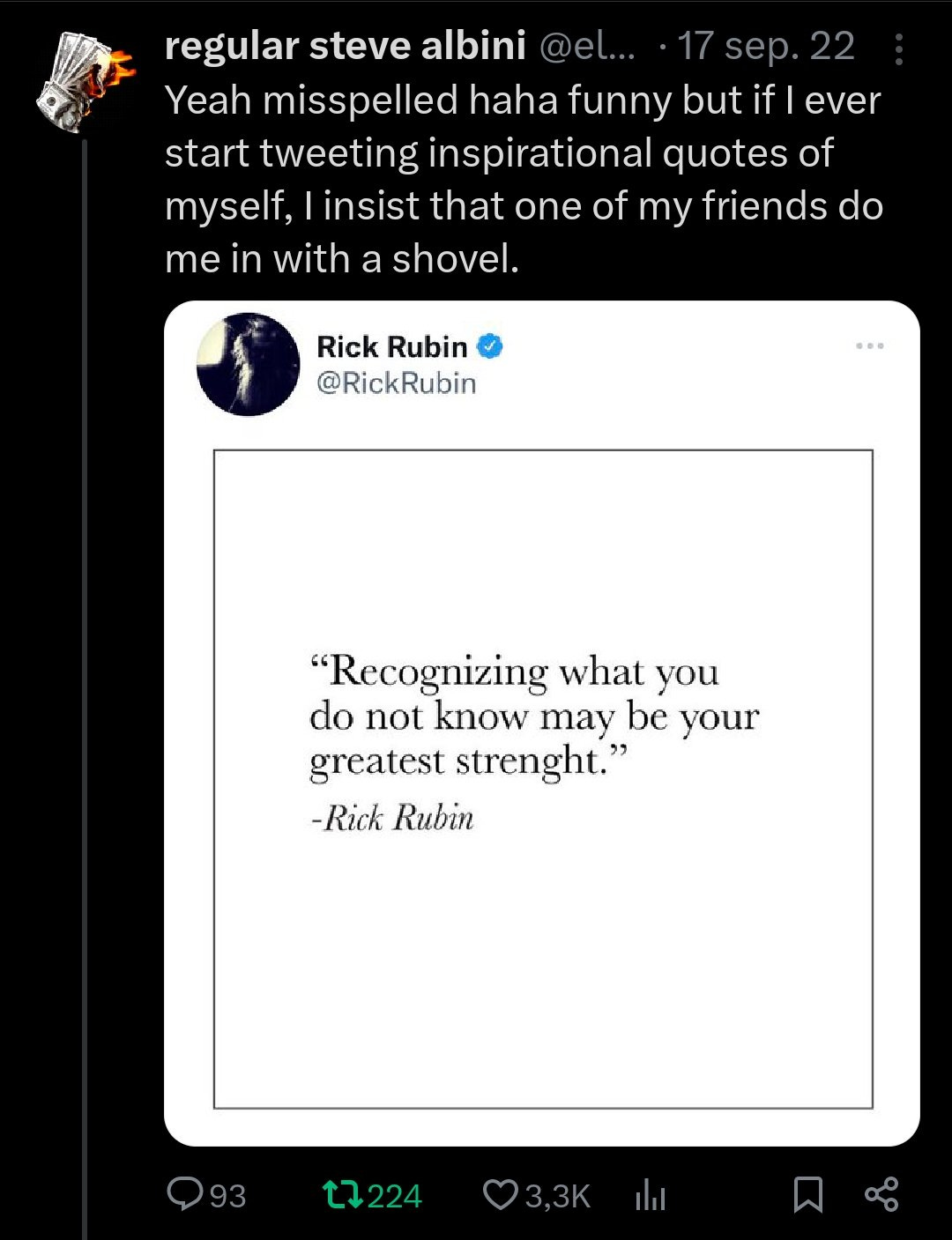

After all my tender talk, I’d like to end this in a way Steve would appreciate—with his own tribute to a renowned…producer.

I vaguely recall emailing his studio Electrical Audio in the early 2000s to inquire about the possibility of doing a Clogs session there. Someone definitely replied!

I looked up details on that night. There’s a review of the show in the New York Times, and info about a Thread Waxing Space archive at the Smithsonian. Its old address 476 Broadway is currently a Citibank. The LinkedIn bio of the venue’s founder Tim Nye says he is currently “taking residential home flipping to scale.” Ok.

Finally, I found this flyer.

I’m pretty sure I was at the Bratmobile gig a few days earlier—lots of time on the Metro-North railroad that weekend. However, I do not recall the excellent band Rodan opening up for Shellac. Which is odd because I eventually fell hard for the group, attending shows by them (or offshoot projects) in Washington DC, Danbury CT, and Knoxville TN — and I documented their presence in my teenage zine (a project which I generally prefer not to discuss).

Shellac’s final album To All Trains was released 10 days after Albini’s death. It’s now available as digital files, or on vinyl LP + CD.

Engineered by Albini? I won’t get into his “Please don’t call me a producer” schtick. Ok, that’s mean. He had a point which he laid out in his famous letter to Nirvana, posted below and elsewhere on Substack.

Pun intended? The language Albini deployed early in his career, to tweak the squares and gain attention, is unforgivable, complicates his legacy, and probably seals off his work from ever appealing to certain audiences. Happily, he did seek to make amends of sorts through good works in the latter part of his life.

Albini said this in an episode of the Kreative Kontrol podcast, around the 49 minute mark of Episode #223. Over the past dozen years, he appeared about once a year on the show—hosted by a nice Canadian guy named Vish Khanna. I’ve been gorging on that archive as I reconcile myself to never hearing from Albini again.

This particular quote is from two episodes which paired him with another culture hero of mine, Ian MacKaye of the label Dischord and the bands Fugazi and Minor Threat. Albini was referring to the death of John Loder, an engineer and entrepreneur who founded a company called Southern Records, which briefly distributed my company Brassland in the United Kingdom and Europe.

Loder died about two decades go, in August 2005. I met him once, a few years before he passed. I remember sitting with him in a waiting room at Abbey Road Studios while The National’s Sad Songs for Dirty Lovers was being mastered.

I asked him for advice on keeping a music business venture alive for the long term.

Loder uttered two words: “Be efficient.”

The rest is a story for a longer set of footnotes.

This Chicago Magazine profile from 1994 was a key find—a critical accounting of Albini’s abrasive early years and the beginning of his life as a public figure.

“Kerosene” is also a plausible rallying cry for self-immolation. The lyric:

Kerosene around, she's something to do

Kerosene around, set me on fire

Set me on fire, Kerosene

Watch the final few seconds of this video clip shot while Albini was recording PJ Harvey in 1992. He literally sets his boots ablaze.

Her band included Brian McComber and Nat Baldwin (two then-members of a band I was managing Dirty Projectors), and ubiquitous NYC figure Shahzad Ismaily. Albini’s review: "I thought the St Vincent cover was pretty good. They got some details right about the sound and the drumming especially. I was impressed." — source

From Albini’s 2012 Reddit #AskMeAnything.

ABC No Rio is a squat-cum-art center on the Lower East Side that began in 1980. The original building was demolished in 2016. They’re still raising funds for a new one. Before Green Day graduated to stadiums, they played lots of venues which seem inconceivable in retrospect. I attended a Warner Brothers CMJ showcase in the early 1990s where they somehow ended up on a bill with the Flaming Lips, Adam Sandler and the Boredoms. Those were different times.

Here is the full transcript of an interview Steve Albini and his two bandmates in Shellac, Bob Weston and Todd Trainer, did for a cover story in latest issue of The Wire.

There is a live compilation of Threadwaxing Space

https://www.discogs.com/release/3201460-Various-Threadwaxing-Space-Live-The-Presidential-Compilation-93-94