I like loners that come to New York City to find their tribe. I feel like I’m one of them. So when Tom Verlaine died a few weeks ago, days after my own birthday, it pinched my heart and made the world feel a bit smaller.

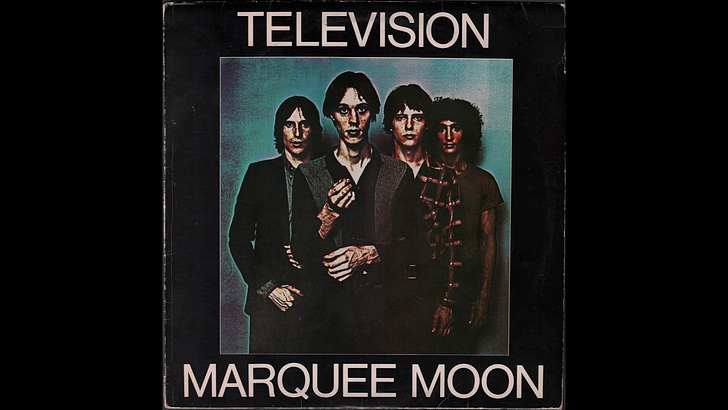

I can’t say I know Verlaine’s entire catalog that well. But sometimes all it takes is one work, inscribed so “indelible in the hippocampus”1 that you’ll never forget what it meant to you.2 This one:

To be clear: I will not attempt to write a Tom Verlaine obituary, because I’d have to rely on Wikipedia and Google and intangible feeling for that. And I want to avoid the cringy, clout-chasing obits one often sees in the social media era. As Verlaine’s predecessor and peer Lou Reed once wrote, seemingly anticipating the horror of brief, obligatory-seeming #DeathTwitter send-ofs:

It always bothers me to see people writing RIP when a person dies. It just feels so insincere and like a cop-out. To me, RIP is the microwave dinner of posthumous honors.

I feel like any personal memorial I might write to Verlaine would be a bit of a RIP.3

So, instead of my own pouring forth, I thought I’d point to the remembrances I’ve run into after his death, which have made Tom Verlaine feel most alive. And I’ll punctuate my finger pointing with his music. Let’s start with his 1992 instrumental album Warm & Cool which he seems to have let go (intentionally?) out of print. A pretty good soundtrack as we kick things off…

This appreciation from Alexis Petridis in The Guardian was one of my favorite overviews—delivering not just The Essential Facts but rather A Consideration Of His Total Community And Vibe.

Verlaine was aloof, introspective and a hugely gifted and original musician, whose playing entwined so completely around that of the similarly gifted Richard Lloyd that it was unclear who was the lead guitarist and who was on rhythm. Bassist Hell was a heroin addict who threw himself around onstage, spiked his hair, ripped his clothes and held them together with safety pins: one of his homemade T-shirts bore the legend “PLEASE KILL ME”.

Verlaine’s friend, collaborator, and former lover Patti Smith wrote an obit for The New Yorker which you may have bumped into, because it went low key Internet viral. I had mixed feelings about it. To me, her piece reflects the wanderings of her poesy and attraction to overabundant metaphor more than it dissects his motivations and mindset. That said, on occasion, she crystalizes an image that cuts through.

He was Tom Verlaine, and that was his process: exquisite torment.

I only wish her editor took a bolder hand with the other 80% of this obviously loving and sincere remembrance.4

A more casual bit of writing from Dean Wareham (Luna, Galaxie 500) in Counterpunch stuck with me more than Smith's piece—mostly because he took the opposite tack.5 Yes his description of the rarified air that Marquee Moon occupies is on point:

The best albums are more than a collection of good songs, they are a sealed world where only that kind of music seems possible, a gathering in time and space.

But it’s the photo that introduced the piece which took me deeper in, and gave an impression of what it would be like to know Verlaine as a person.

There is a flash of humor in this photograph that his music didn’t always reveal. I value it all the more for that contrast. Verlaine’s guitar playing is so crystal cut and perfect. His interactions with other guitarists are so much like a spider-web, it’s almost impossible to imagine the craft that went into it. And temperamentally his music is so…Buddhist? Stoic? Flashily introverted? The right phrase evades me. But to see this visionary musician so clearly playing the goofball roll with a peer… The intimacy of that…it’s priceless. We think of Verlaine’s intricacy and stillness; this photo reveals the silliness of a guy named Tom.

Want more rarefied air, though? The music is there for you. Try this track from Wareham’s old band Luna called “23 Minutes in Brussels” which features Verlaine on lead guitar throughout:

The remembrances of Verlaine that I enjoyed the most, however, are the ones that portray not his music, but his life as a kind and ghostly wanderer in our perfect city. This piece in Lithub depicts his daily ramble to Manhattan’s legendary (now somewhat tarnished) used bookstore, the Strand.

If you swung by the carts that line the Strand’s exterior, where all the books cost $1-5, odds were good that you’d run into Verlaine, searching for grails that had been shunted out to the street. “Pre-COVID? He was there every day. For at least an hour or so,” said Peter Calderon, a Strand employee of more than 15 years. A former employee, Alice Richardson, described him as most employees remember him: “He’d be quietly browsing the dollar carts at night, smoking in an overcoat.” . . .

“Everyone who worked there knew he was a regular,” said Christopher Pirsos, another former bookseller. “I don’t think he ever bought a book from inside. He almost exclusively bought cart books.”

If you want more of his life as a “Cart Shark” look no further than this lovely bit of writing from George Szamuely—a self described “senior research fellow at the Global Policy Institute" who admits “I am not really familiar with his music, and cannot therefore add to the many words of appreciation that others have contributed,” before posting about how much he appreciated Verlaine not as a musician, but as a notable, much beloved fellow book browser.6 I've excepted a bit of Szamuely's piece in the footnotes to give you its flavor.

It's like seeing Lou Reed through the lens of his Tai Chi practice, or Bob Dylan through his hobby of sculpting iron gates. In other words, it probably tells us more about Verlaine’s “happy place” than anything you’ll ever hear on record.

I’ll leave you with a pair of videos I encountered in the days after Tom Verlaine died.

First, this clip of Television from 1974—maybe the only known7 footage of the band performing with soon-to-depart founding member Richard Hell—from a public access television program called The Underground Tonight Show.

Apparently John Lennon saw it and his reaction was captured by a reporter from Melody Maker.

On TV next came a group called Television, and Lennon sat fairly transfixed. Television are so bad they’re good. They can barely play their instruments and they are very short of money; they’re young and dressed in rags. But they have a spirit that’s irresistible, and John immediately identified them as a parallel with The Beatles in their Hamburg days. “Yeah, I can relate to them, they’re exactly as we were. Skint and loving every minute. They sound terrible but they’re OK!”

Next a buried treasure, from a 1984 solo album by Verlaine, previously unknown to me. Shades of Jan Hammer’s theme for Miami Vice or Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit,” it sounds like cocaine, early drum machines, and a snapshot of New York City caught between the triumph of the new wave and hip-hop’s slow, mighty rise. It’s a portrait of a musician willing to evolve.

I’ll end this by breaking my promise. Maybe this cloud of other people’s memories makes for a great Tom Verlaine obituary? At the very least, it probably provides a sense of what the guy might actually have been enthusiastic to talk about if you’d bumped into him.

You changed the world for a lot of people Tom. I can’t imagine how life felt in the aftermath of that. You poked about and kept making things for almost a half-century afterwards with no Rock & Roll Hall of Fame acknowledgement (whatever that silly institution represents), and no platinum records that I’m aware of. Certainly no riches. (I recall reading an article in which you praised be that you purchased a Chelsea apartment before the art world and Google found the neighborhood and gentrification set in.)

Is it a failure of collective willpower that we never managed to get Jann Wenner or the record industry to give you a plaque? I suspect, like discovering a gem of a book on a clearance rack, you felt just fine about your place in the world. Never ossified by honors from an undifferentiated mass who only cared about you as a momentary blip in pop culture. But, rather, loved in hushed tones by the heads that admired you, whispering your name like a secret, keeping that work alive one by one by one by one.

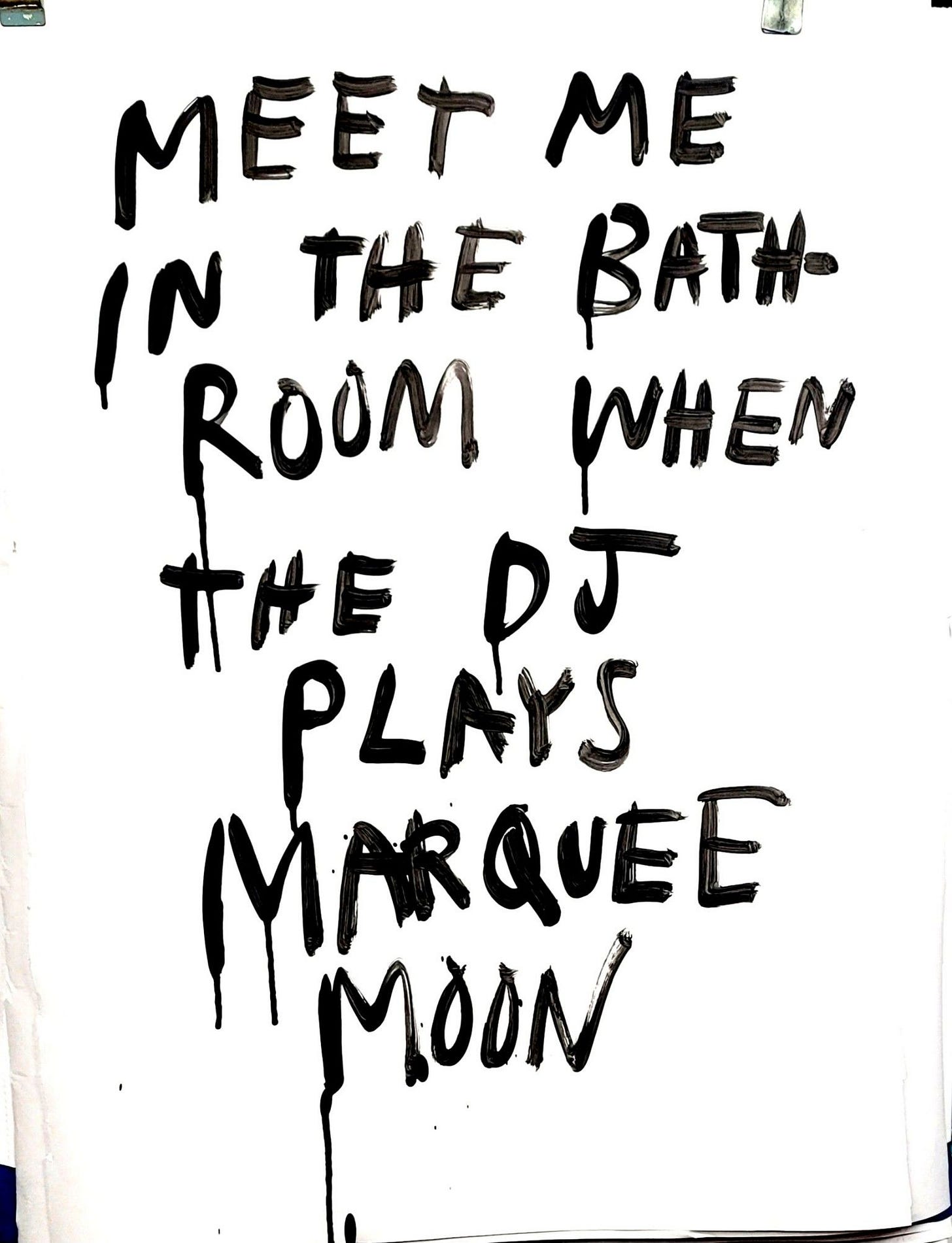

p.s. I don’t know if it’s even possible to fully absorb the manic riffing of writer/bartender/NYC scene figure Zachary Lipez, but I certainly paused with moments of recognition while reading his take on Verlaine—“Eight Unfinished Essays On Marquee Moon.” The final quote below offers a bartender’s perspective, and the pic below is also from Zach’s blog:

But it’s a rare album that is sufficiently a vibe unto itself to carry as much weight as a bar’s zany decor or the relative shirtlessness of its bartenders. To qualify, an album must be more than ambient and less than dominant, with a command that is subtle enough to be a prickling under the skin rather than something to sing along to or retreat from. It’s rare for an album to be background but somehow not; iconic but still indefinite enough that the bar vibe communicates a welcoming coolness rather than an intimidating cool.

Extra credit:

I’ll finish this post with two other, unrelated bits of writing from the Substack platform that gloss on why I feel so strongly about the work of Tom Verlaine and Television. First, a quote about why lack of “success” can be good, and second how ephemerality can, in fact, serve to make artwork seem more evergreen.

Quote number one is from Sasha Frere Jones,8 best known for his decade-long stint as music critic at The New Yorker. He posted about Elon Musk’s purchase of the Twitter platform, which led Sasha into a cascading, passionate rant on why our Internet economy and culture often feels so unsatisfying:

“Our motto is ‘LIFE IS SHORT, SCALE IS THE ENEMY OF THE GOOD, AND ALL WE HAVE IS EACH OTHER.’ That’s an easy thing to say in all caps, though I would like to add that I believe it… I have no idea how to fix (or maintain) a publishing house or create a social network. The only thing I feel certain about is scale. Scale is the central lie of capitalism. You, the employee, are told to scale up for your benefit even though the only confirmed beneficiary of that scaling up is your employer.”

Is it possible that Verlaine’s lack of wide renown is actually one of the things that makes him so great? Certainly that he’s mostly a musician’s musician, an artists’s artist, makes his art more appealing and deeply felt to someone like me.

Quote number two is from Dan Fox, a former, long-time editor at the art magazine Frieze.9 He took a skeptical view of the critical canonization of photographer Wolfgang Tillmans after his recent show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Dan writes not as someone just discovering Tillmans at a retrospective, but as a longtime fan. His piece captures a wonderful paradox of what makes Tillmans’ work lovable. It possesses an ephemerality that makes it feel of the moment, but it also has a depth that allows you to enjoy different facets of the work at different stages of one’s life:

“There was a time when I would have gravitated more to…his portrait of musician Richard D. James, the Aphex Twin, posed outside a suburban garage door, the one that I cut from an issue of i-D as a teenager, and had tacked on my bedroom wall. Now I just want to see the play of light across desiccated fruit and rubber gloves.”

The idea here, I think, is that you simply cannot appreciate Tillmans by “taking in the greatness” at a retrospective. You have to live with his work for awhile. I suspect Verlaine’s music has functioned similarly in my life. I felt one way about him as a teenager in the 1990s, browsing the racks of used and discount compact discs at a record shop on St Mark’s Place, making my first forays into the punk/alternative canon. Frankly I liked it but I didn’t totally get it. I just knew that Television was a cornerstone and that I had to like it.

I feel entirely different emotions about his music in middle age, during the first quarter of the 21st century where he seems like a classic example of a lost city, and a lost world—and the feeling of listening to him captures all that loss, all that history, so much feeling, all the music that he’s influenced that I’ve come to know and appreciate over the past three decades.

Mostly I appreciate that he made something perfect. Not many people can say that:

What other pieces of recorded art comes to mind as just such singularities? My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless ~ Q Lazzarus’s “Goodbye Horses” ~ Mary Margaret O’Hara’s Miss America ~ Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea ~ D’Angelo’s Voodoo. Among many others. I thank the world for playing host to them.

I did manage a Lou Reed remembrance when he passed which I’ll link to right here, because I’m still low key proud of it.

We should only be so lucky to be as loved as Tom Verlaine was by Patti Smith. As Steve Albini put it in a Tweet:

I’m not the only one to note Smith’s kinda borderline hammy tendencies. As Warehem put it in his obit: “His friend Patti Smith said somewhere that Verlaine ‘plays lead guitar with angular inverted passion like a thousand bluebirds screaming’ — but that says more about her than it does about him.”

As Szamuely says in the introduction:

His interests were extraordinarily wide-ranging. He would greet me very excited, having found some book about traveling through New York in the 1930s or a volume of verse by an obscure poet from the 1960s or a vegetarian cookbook or the score of a long-forgotten musical or a memoir of the music scene in the 1980s. He would often come over with a book to where I was browsing and recommend that I buy it. Since, as likely as not, the book was about something I didn’t know much about—and the book only cost $1—I would generally follow his recommendation. However, I soon came to notice, he never reciprocated. Not once did he follow my recommendation. Out of politeness, he would place the book back on the cart and promise that he would buy it the following day…

When Tom wasn’t reading, browsing or tidying up at Strand, he would be engaged in lengthy, energetic conversation with almost anyone. He was friendly, charming and modest, and always interested in what others had to say. He would chat happily with a young Math teacher about the space-time continuum, with me about politics, with someone else about computers. He seemed interested in everything… It was almost as if Tom were the host of a daily Strand party. I would arrive at some point in the evening, stay for an hour or so and leave: he would be there when I arrived and still there when I left.

Find Sasha’s Substack and the particular post I quote, over yonder:

Find Dan’s Substack—and the article which I quote—over here:

Thank you for writing this. I feel exactly the same way.

Thank you. Great post. Not enough people writing and talking about this legend.