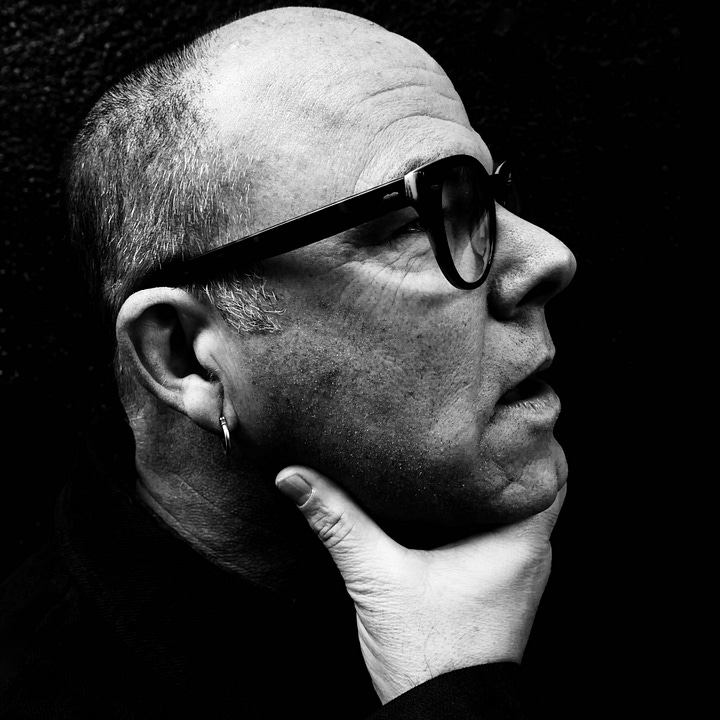

A conversation with David Grubbs (Gastr Del Sol, CUNY professor, Squirrel Bait)

includes several gateway playlists to contemporary, post-genre instrumental music

Hi, this post is a free sample from the Artist Primer section of my mixtape delivery service, which offers introductory playlists for over two dozen of my favorite musicians. That section is available only to paid subscribers. You can get an annual subscription for $25.

# of Tracks: about 20 recordings

Length: approximately 2 hours

Themes: a key figure in underground & experimental music since the mid-1980s ~ post-rock & post-hardcore ~ a kind of Zelig-figure in scenes spanning Louisville, Kentucky; Chicago, Illinois; and, currently, Brooklyn, New York ~ recordings that re-arrange strands of musique concrète, American primitive guitar, and rock/folk into a unified, listenable, and progressive whole

Links: Spotify | Apple Music | YouTube

For over three decades, David Grubbs has been a key figure in numerous boundary-pushing music scenes. As a young adult in the 1980s, he participated in the explosion of underground music emerging from Louisville, Kentucky,1 co-founding the post-hardcore band Squirrel Bait, whose sound shaped indie and alternative music to come. In those years he also made zines that put him in dialogue with iconic, recently deceased producer Steve Albini and the Chicago scene; in the 1990s, Grubbs moved to that city and created the uncategorizable duo Gastr del Sol, a partnership with Jim O’Rourke which regularly featured contributions from dozens of other musicians. The band’s fusion of folk, classical, and electronic experimentation helped define the post-rock genre.

“Post-” is a word that comes up frequently in describing Grubbs' work—an acknowledgment that genre is particularly slippery in his music. Somehow his work is simultaneously esoteric (the post- part) and concise and listenable enough that a fan of standard-issue genres will comprehend it (that’s the -rock or -hardcore part). I’d place him alongside artists like Dirty Projectors, L’Rain, Brian Eno, Irreversible Entanglements, Animal Collective, and Aphex Twin—contemporary music which offers deep pleasure, but requires openness and a willingness to e-x-p-a-n-d your mind to fully appreciate. Cerebral music that does not sacrifice joy.

Grubbs moved to New York City in 1999 where he remains a diligent, prolific presence across multiple fields—recording, writing, visual/performance art, and teaching. He’s quietly influential and unusually open to the behind-the-scenes practices that keep weird music alive, such as community- and institution-building. He teaches at the City University of New York’s Brooklyn College, serves on the boards of non-profits like Blank Forms, and records prolifically. (I count well over thirty albums he’s released since the turn of the century, increasingly in a conversational, collaborative mode.)

Over 75% of the recordings on this AHB’s Goodies playlist feature Grubbs, while the remaining bits highlight key influences on his work. I hope it serves as a good introduction. I’ve been a member of Grubbs’ cult following for about thirty years and have never doubted that decision. The Kool-Aid is delicious, a purely aesthetic pleasure with not a trace of the contemporary death cults that seem to be running rampant over American society right now. (Yes, this interview touches upon our current political moment.)

Find the playlist on… Spotify | Apple Music | YouTube

Previous AHB’s Goodies Q&As

Mia Doi Todd: a chat about "Music Life" & an "ambient" conversation

Richard Reed Parry: music for heart & breath & floating & falling & dreaming

A conversation with David Grubbs

# of Questions: less than 10

Length: about 3,000 words

Themes: the influence of cinema and poetry on music ~ how a political consciousness plays out in art ~ storytelling about recording, touring & the act of performance

Question: At least three of the songs from my recent Eeriemysterious playlist were picked from the What We Were Listening To Instead of Practicing playlist created to celebrate We Have Dozens of Titles, your recent Gastr del Sol box set.2 In the 1990s, that project was my gateway drug to so much amazing music. The activities of the band—and the Drag City label you recorded for—shaped my perspective on figures ranging from Van Dyke Parks and Scott Walker; the then-trendy world of post-rock; and even more obscure historical predecessors like musique concrète or American Primitive guitar.

I still think of Gastr as a personal keystone in understanding the possibilities of long form, instrumental recordings as a constructed or cinematic space. Do you agree that is a good way to interpret what you and Jim O'Rourke were doing with that project? (i.e. making little movies for the brain via recorded sound)

Answer: Musique concrète—considered broadly, and not in any strict Schaefferian manner3—and cinema were two of the most important reference points when Jim and I started working together in Gastr del Sol. My instinct is to hold them as distinct traditions and not to be quick to collapse the two or focus primarily on their commonalities. The first Gastr del Sol recording that Jim worked on was the 20 Songs Less EP (the title a nod to Laura Riding’s “Twenty Poems Less,” one of my favorite of all titles, and an idea—that artistic production can be a kind of counting down—to which I keep coming back), and I think we understood his role as “editor,” making a collage work out of short instrumental pieces by John McEntire, Bundy K. Brown, and me, although what he did surely also counts as composition.

During the first couple of months Jim and I were working together, I attended group concerts at Northwestern and at a club in Wicker Park called The Hothouse in which Jim presented a new tape piece of his called “Rules of Reduction”4 which was later released in Metamkine’s Cinéma pour l’oreille series (speaking of collapsing musique concrète and film5), and I remember the vividness of the impression the piece made as representing one distinct space after the next, like opening door after door and being continually caught off-guard by the discontinuity. I was intrigued by what Jim was doing with regard to musique concrète—just as I was intrigued by what he was doing as an improviser or his insights into the work of Morton Feldman, John Cage, and others—and immediately sensed that all of this was fair game for the group we were getting revved up. He was of a similar opinion.

One of the reasons why the playback of “Rules of Reduction” in a concert setting threw me for a loop was that even though I had been a listener to recordings of experimental music for some time, it was an experience of unbroken concentration. I had similar experiences sitting with Jim in his bedroom in his parents’ house listening to records—“practicing”—that he really modeled a disciplined listening that he seemed to take as second nature. (There was no congratulating ourselves for listening well.) In that way, we spent time listening to Van Dyke Parks’s Song Cycle as well as pieces by Luc Ferrari, talking about them both as, among other things, tape music.

I am not familiar with the Riding book, but appreciate how that throws another medium into the recipe of What Makes The Music of David Grubbs: music, movies (Cinéma pour l’oreille), and literature—or, at least, a form of literariness.

Does Riding have a poem that "got you" like William Carlos Williams' This Is Just To Say6 once got me? I am hoping this chat takes full advantage of the multi-media qualities inherent in the Internets—even if it's just sharing examples of individual artists’ work in the footnotes—and I'd like to point readers to some of your reference points.

I find Riding's poetry extraordinarily difficult and almost equally difficult to remember. I liked wrestling with the poetry, but was also curious about her from a biographical standpoint: she lived for a period in Louisville and quit writing poetry in 1941 and published invectives against the practice but nonetheless was awarded the Bollingen Prize in 1991. When I started working at the academic quarterly Critical Inquiry as a graduate student, I was fascinated to unearth her combative unpublished correspondence to the journal. The fact that she quit poetry—and came up with that strange title "Twenty Poems Less"—these were the things that drew me in.

I love that admission—that sometimes the life of an artist can be as impactful or influential as the work itself.

How your music unfolds always bring to mind more narrative or literary mediums. I hear it in the poetic nature of your vocals (enjambment!) and in that quality you spoke of ("the opening door after door caught off-guard by the discontinuity") which feels in line with surrealism, or the language of film (jump cuts, editing, collapse of physical space). More than most audio work, your recordings trigger a kind of "reader's mindset." They inspire and stand up to close listening.

I thought that I was a close listener until I met Jim. It’s not for nothing that he aced his Invisible Jukebox for The Wire while I did a somewhat abysmal job, not even recognizing a Tortoise track for which I may have been present during the recording.

Has the way you express yourself in the medium of recordings changed? (We can treat Bastro / Gastr del Sol as year zero for your history as a recording artist, or go back to the hardcore/indie days if you prefer.) I wonder if your book Records Ruin the Landscape—and engaging with John Cage's legitimate discomfort with recorded media—affected your recent practice. I think of your last 5+ years through the lens of performance—frequent, varied, and curious encounters and collaborations with voices new and old—peers and “up and comers” so to speak.

Certainly these have also been your most prolific years as a recording artist—collaborative albums with Susan Howe, Mats Gustafsson, Manuel Mota, Taku Unami, Loren Connors, Ryley Walker, Eli Winter, and Jan St Werner. (I'm sure I'm missing some!) But am I right that these recordings have shifted into a more documentary mode?

It’s possible that Gastr del Sol will be the apex for me of more experimental, previously untried recording practices.

What else among releases of mine stacks up vis-a-vis that mode of working? Maybe Translation from Unspecified, my duo album with Jan St. Werner, or the current project that Jan and I are working on with Jules Reidy.7

Moving toward a more documentary recording practice without a doubt had to do with the fact of no longer working with Jim (or working in his home studio, where we had an endless amount of time to try things out as well as to polish the work to our satisfaction). I would describe it less in terms of a purposeful, aesthetic realignment—no gauntlets thrown, no manifestos distributed—than as being in the nature of particular collaborations and working environments. Come to think of it, much of the detailed, worked-over character of the recent music with Jan has to do with access to the Mouse on Mars studio. Going through the archival Gastr del Sol material when compiling We Have Dozens of Titles8 did make me ask myself if the act of recording and producing for me could again become more exploratory.

Do you care to discuss your new solo9 album Whistle From Above? I'm thrilled by the record because there are elements—I think of the almost classical guitar aspects of "Hung in The Sky of the Mind"—that struck me as quite novel in your discography.

I'm curious about the timeline—how long did this project take to conceive and create? I believe it is your first LP without a named collaborator since Creep Mission in 2017, so there's been a long gap. Did this record entail a lengthy woodshedding process? Did collaborators play a distinctly different role compared to your recent duo records?

I think it’s fair to consider it my first solo album since Creep Mission, which also came out in the bleak first months of the first Tr*mp administration eight years ago. (The title was my attempt at a talismanic inversion of “mission creep”—much discussion at the time about how to protect oneself from “mission creep” and burning out protesting.) In 2023 the Chicago art gallery and publisher Corbett vs. Dempsey released a solo recording of mine called From Red Black to Black, from Blue Black to Black, an album of reworkings of my soundtracks for pieces in the exhibition of the same title by Josiah McElheny. That was to have been released on CD with an accompanying book about Josiah’s work (or, more likely, a book with an accompanying CD), but as of yet it’s still exclusively a digital release

The earliest recordings of Whistle from Above material were made the night after the 2020 election—also the night that I recorded the piano part for Concordance, a duo album with Susan Howe—and I remember driving to the studio in Mount Vernon, NY (the symbolism!) and wondering what kind of hell was likely to transpire. Most of the pieces on the album are ones that I’ve been playing solo for a while, which is a pleasant change from writing in or just prior to entering the studio, and then after a year or two of concerts feeling that you’re ready to really nail the thing. Returning to the archival Gastr del Sol material did convince me that the album should be more than a document of my solo playing—but I also wanted to keep the arrangements spare and have the guitar present in all of its detail.

One note: I wish I could play guitar like Rhodri Davies plays harp. On “Hung in the Sky of the Mind,” that’s Rhodri playing harp and me playing piano. “Hung in the Sky of the Mind” was the runner-up for album title. The phrase appears near the end of Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts, describing the fleeting impression of a performance, just before it vanishes.

I'd be interested in hearing a bit more about how politics expresses itself in your music. Based on your last response, you have clearly marked the time around making your recent solo records to America's deeply troubling political direction. Do you think of your recordings as having "political content"? Or is it, perhaps, a bit more like political inspiration—the sound of emotions sublimated into music, rather than direct commentary.

If I'm not mistaken, Whistle from Above is vocal free, and your vocals seem to be growing more sparse (if not entirely absent) from recent solo records. To be clear: It's not impossible for me to conceive of instrumental music being political!10 I just want to hear how you think your music engages with politics!

Politics are always present in my daily life—it’s hard to imagine otherwise. I was kind of a news junkie as a teenager; the first time that I ever wore a suit was to sneak into the press room at the Reagan-Mondale debate in Louisville in 1984, when I was a senior in high school. (I had applied for press credentials for my fanzine, but was turned down.) I sat with people from the Los Angeles Times and apart from the terrible foreboding that Reagan was going to destroy Mondale in the election, the whole evening was electric. That experience played a role in my deciding to go to Georgetown University, but when I arrived there the Reagan revolution was in full-swing, and I couldn’t believe the idiocies being spouted by Young Americans for Freedom and similar student groups.

It sucks to date certain events in one’s life relative to the horror of the two Tr*mp administrations. As of the date of answering this question [February 12, 2025], disastrous and frequently illegal and/or unconstitutional executive orders are appearing on a daily basis, such that addressing any single one of them almost feels beside the point, which is clearly the aim, “flooding the zone,” etc. But I guess I’ve never wanted to block out politics, nor have I thought of music as a respite from politics. Music has also been my ticket to spending a decent chunk of my adult life outside of the United States, and encountering a multiplicity of perspectives is a good part of my political education, and I’ve found it bound up in the cultural activity of engaging folks internationally.

Re: the political content of instrumental music, something in me clicks with your asking if it has to do with sounding particular emotions—yes. When I was writing more lyrics, I’m not sure what would have registered as being explicitly political. The occasional title: “The World Brushed Aside” came about at the time of the insane George W. Bush administration decision to invade Iraq despite global condemnation.

Your answer reminds me why I've built my own life in the arts: Despite the hardships, impoverishment, and other complications, it provide a bit of space between my day-to-day concerns and the meat-grinder of capitalism. The admission that you were a news junkie who flirted with a Washington DC life is revelatory....and a bit confusing!

Today's politics are so polarized and angry, and one forgets those qualities used to be less central to public life. You always strike me as particularly rational and level-headed—a bent which I also hear in your music. Even when your recordings feature screeching guitars, synth static, or other audio ruptures it feels like a rather contemplative, even calm version of it—a beautiful form of noise unique to you.

I suppose I am fairly level-headed. I’m not sure that it was always so, and what I feel most alienated from in my own musical backstory is my shouty singing in the group Bastro—that’s something I can’t imagine doing again. The reasonableness to which you refer—I don’t know why I find it so funny; it is itself a reasonable description—has to do with the fact that I’ve been a professor now for more than a quarter-century and that it’s brought with it a certain responsibility to others that I didn’t previously have. And especially since teaching at a public institution like CUNY and having a vastly more diverse group of colleagues and students than when at a private university—I think it has made me a more modest and genuinely (and not just intellectually) curious person.

Perhaps your alienation from shouty vocals, will distract from my not addressing your formative and influential years in the hardcore and post-hardcore scenes.11

Let me turn to another strand of your work—the book projects. I've been re-reading The Voice in the Headphones (2020, about the studio experience) and, in the last decade, you've also published Now that the audience is assembled (2018, about a performance) and Good night the pleasure was ours (2022, about touring). And earlier you mentioned a new song which references a Woolf text about "the fleeting impression of a performance."

Have you thought about what's drawn you to make this series of works about the life of an artist / performer / musician? I've imagined the books deriving, in part, from that dual career as both a professor and artist. That teaching others has made you more self-reflective about your career. Or that these books are pedagogical tools refracted through poetry.

Regarding the impulse behind the trilogy of books that begins with Now that the audience is assembled, it first of all was a pendulum swing from Records Ruin the Landscape, which has so much jumping back and forth in time—it’s a comparative study of different generations of listeners—and painstaking reflection on technological mediation. I wanted to write about the experience of performance—in particular the situation of a kind of concert of experimental music I’d come to know both as performer and audience member—and I wanted to write a long narrative poem. (I should also say that Ben Lerner12 dared me.)

When I was a senior in college, I sent a batch of micro short stories to the writer and artist Guy Davenport. His response literally contained the word “ugh”! One phrase that appeared in his letter was “when you have stories to tell you will tell them.” When I was 21 years old I thought this was patronizing advice. But I do in fact recognize that I have stories to tell, and that trilogy of books was the way in which I imagined I’d most enjoy doing so.

Your CUNY faculty profile lists your research interests as "sound art, experimental music, pop music, sound recording." As a final question, I’d like you to reflect on how your students—who I assume are generally younger?—engage with those mediums today.

Has their approach to art-making changed to meet our screen-saturated, digital era? What attitudes have felt novel, contemporary, or even unimaginable to a 1980s-era David Grubbs? I’m looking for broad trends.

Today I primarily work with Sonic Arts MFA students at Brooklyn College and doctoral students in Music at the CUNY Graduate Center, and an aspiration that I periodically hear voiced is “How can I get a job like yours?” because people have a hard time imagining that they’ll be able to make a living off of their music exclusively. (I’ve been making records for Drag City for thirty years and they provide quarterly statements and pay royalties like clockwork, and still it’s only a fraction of the time from the past three decades in which I would have been able to survive exclusively as a professional musician.)

Many of the students that I work with are involved in more immersive, durational performance practices or make pieces that can function as installations, so there is some aspect of this practice as a refuge from screens or, more to the point, networked demands on their attention. But there are also many who incorporate video in their work and for whom projections are an important part of what they do, and their musical practice is part of a continuum that is audio-visual.

Maybe the biggest bummer to the 1980s-era version of me would be that a lot of the undergraduates I’ve worked with just can’t wrap their heads around the value of music or arts criticism more generally—I grew up living for that stuff.

One of the bigger surprises, and by no means a bummer, would be the fact that, particularly using digital tools, music or sound becomes one aspect among many for which people have real facility, and DIY comes to encompass multiple disciplines and media. My most successful students become educated in multiple lineages of artistic production. The optimist in me is happy to recognize and applaud that.

The playlist includes songs such as…

^ Gastr del Sol: “The Seasons Reverse”

^ Gastr del Sol: “Black Horse” (live, 1995)

^ Gastr del Sol: “Hello Spiral”

Extra credit:

• Eeriemysterious instrumentals: This is the playlist which inspired me to approach David for an interview. I hoped our chat would be part of the initial post, but he was in Germany, busy with a fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin. I’m glad we still made it happen, giving me a chance to highlight this playlist again. It features non-ambient instrumentals that demand your attention.

• So you wanna get into…Jim O’Rourke: It’s worth exploring the discography of Jim O’Rourke, Grubbs’ partner in the Gastr del Sol project. I discovered this post from a seemingly dormant newsletter, Tusk Is Better Than Rumors, thanks to the Substack algorithm. It offers a chatty overview of O’Rourke’s catalog as a producer, collaborator, and solo musician—a sometimes-cheeky introduction to a musician whose world is as rich, dense, and surprising as that of Grubbs.

• a pair of David Grubbs-curated playlists: For his latest releases, Grubbs curated two playlists featuring work by peer artists, each highlighting different aspects of his own creativity. Both are available on Apple Music and Spotify. David Grubbs Collabs focuses on duo recordings by friends, influences, and collaborators like Tony Conrad, Wendy Eisenberg, and Loren Connors (pictured below, at left). My favorite discovery was the wild, détourned Italian folk chorus on Silvia Tarozzi and Deborah Walker’s “La lega”.

I’ve spent less time with a newer playlist focusing on a Deeply Personal Brand of Minimalism, but I was already familiar with the lead off track, “Sound of an Unperplexed Wren,” in which sound artist Brian Harnetty13 builds a composition around spoken word tapes of monk and writer Thomas Merton.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to AHB's Goodies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.